The Electronic Intifada 9 July 2005

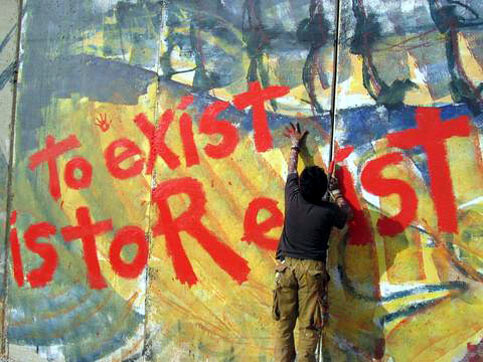

An artist paints a red handprint at the mural near the checkpoint at northern Bethlehem. The artists were stopped by private security agents of the wall’s construction company near the checkpoint in Bethlehem and later by the Israeli occupation forces. (Omar Tesdell/ICB)

The Israeli Wall—the so-called security fence- is a daunting and ominous matrix of social control and demographic separation that is currently planned to be 670 km long. It is thick and concrete, 8 meters high, and at some points 104 meters deep.

The Wall is three times as high and twice as wide as the Berlin Wall. It is surrounded at a distance by nests of barbed wires, rolled up like stacks of hay piled high around it. High voltage circuits run through the so-called “smart fences,” three meters tall that line the perimeter of the barrier. Between the fence and the wall is trench, over two meters deep, studded with piercing metal spikes. Outside the smaller fence, the Israeli military has paved a path of finely ground sand that is groomed to make footprints visible. At certain intervals, there are 10m vertical steel poles housing highly powered stadium lights and surveillance cameras.

Adjacent to the Wall, on the Israeli side, stand huge and foreboding turrets and watchtowers where Israeli observers and snipers are stationed. The Israeli military has defined the area of the Wall to be a “military zone,” and soldiers have orders to shoot to kill upon the discretion of the commanding officer.

As part of the ongoing process of settlement that began in the Occupied Territories after Israel occupied the West Bank and the Gaza in 1967, the wall dramatically alters the conditions of life in the Occupied Territories of Palestine by establishing and consolidating a set of territorial arrangements that attempts to physically ensure that most of the existing and illegal Jewish settlements in the West Bank and Gaza are there to stay.

By virtue of its route, which is not along the internationally recognized borders of 1967 (the Green line), the wall annexes fifty-eight percent of the West Bank and confines the Palestinians to a ghetto-like existence. Extending from the north of the West Bank area around Jenin and far southwest to Tulkarm, it essentially closes off the entirety of the Palestinian town of Qalqilya. Winding its way south towards East Jerusalem and Bethlehem, it physically encloses over seventy-eight Palestinian and Arab communities, such as Battir, Nahhalin, Ras Al-‘Amud, Ras Atiya, Abu Farad to cite only a few.

The Wall, the construction of began in June 2002, has severely disrupted and profoundly encumbered daily life. It has undermined and wretchedly destroyed the social and economic fabric Palestinian civil society. To make room for its path, entire orchards and olive groves have been uprooted. Farmers have no access to what little remains of their arable land. Thousands of Palestinian homes—over 42,165 in the West Bank-have been demolished by the Israeli military. Tens of thousands of dunams (1 dunam = 1000 square meter) have been confiscated by the Israeli military in this systematic process.

The wall at Kalandia checkpoint separating Ramallah and Kalandia refugee camp from ar-Ram and northern Jerusalem neighborhoods and Palestinian villages (Arjan El Fassed)

Check-points and road-blocks obstruct Palestinians’ unfettered access to schools, health clinics, and work. Families have been physically separated; and, in one instance, a house was purportedly divided in half. In Qalqilya, the wall rises to such a height that, it is said, one can no longer see the sun set. Life in the Occupied Territories of Palestine has been reduced generally to an utterly debased form of collective imprisonment. In the area surrounding the town of Qalqilya alone—-includes Ras Atiya and Arab Abu Farad—about forty thousand Palestinians remain virtually enclosed by the Wall.

In October 2003, the check-point at Qalqilya was completed closed for a period that lasted several weeks, shutting off Palestinians in the surrounding area from the rest of the world in what is essentially a more or less closed ghetto. Villages such as Rafat, Deir Ballut, Az-Zawiya, have one only one exit, and, in the case of Deir Ballut, the military checkpoint is closed every evening at 19:00. In the town of Jayyus, in the district of Qalqilya, the Israeli military opens the check-point briefly. An Israeli military sign in Arabic announces the check-point is open from 7:40 to 8:00 am, 2:00 to 2:15, and 18:45-19:00, only fifty minutes a day.

The human cost of the occupation in general and the construction of the Wall in particular is enormous. Since September 29, 2000 to June 20, 2005, 3,625 Palestinians have been killed, nearly 30,000 injured, over 7,000 with live ammunition fire. In the long history of the occupation that began in 1967, roughly 400,000 Palestinian have been detained at one point or another. Calculated as proportion of the total Palestinian population in the West Bank and Gaza, 40 percent of Palestinian men have, at one time or another in their lives, been imprisoned.

The wall has severely disrupted the free movement of Palestinian, Druze, Bedouin and Arab residents of the Palestine Occupied Territories. In its current configuration, the Israeli Wall intersects Route 65 from Qalqilya to Nablus at five different and separate points, making travel to the larger city of Nablus, where most life-saving surgical procedures are performed, almost completely inaccessible. It geographically divides the West Bank latitudinally in half, making travel between the north and south impossible.

What was once only a short distance-20km-between Qalqilya and Nablus is made all the more insurmountable by a series of obstacles, checkpoints, road blocks, and the physical barrier of the Wall which together as a system of geographical enclosure forces Palestinians to drive an extra few hundred kilometers-at least several hours-to get to the nearest major hospital that us equipped to deal with critically ill patients. In one recent case, a woman with a complicated pregnancy was denied an exit permit at Israeli checkpoint near Qalqilya. She was giving birth to twins on the spot, yet the Israeli soldiers refused to let her drive to the nearest hospital for surgery. Both babies died.

Entire villages are cut off from their crops—mostly citrus and olive groves. In the Salfit area, the Israelis seized roughly ninety percent of the land in order to incorporate the Jewish settlements of Ariel and Kaddom on the Israeli side of the wall. At certain points the wall literally juts abruptly into Palestinian territory in order to claim the Salfit area for Israeli settlements. As if that were not enough, the Wall’s trajectory seizes some of the most fertile soil in the region on the Israeli side, between the Green Line and the Wall itself. Daily existence in Gaza fairs no better. Although widely celebrated as the end of the occupation of Gaza, the Sharon disengagement is actually the exact opposite: it is the armed, military encirclement of Gaza by the Israeli military.

From September 29, 2000 to December 2004, 18,311 homes in Gaza have been destroyed. In the Rafah alone, which Israel invaded in October 2003, the Israeli military destroyed 120 houses, shut down 114 refugee shelters, and in that month alone left 1,240 left Palestinians homeless. From the period of September 2000 to December 2004, over 16,000 people were rendered homeless. The aim of all this, which Ariel Sharon has admitted quite candidly, is to prevent Gaza from having any external contact with the outside world by land, by air, and by sea. Indeed, it is far more costly for Israel military to continue to occupy Gaza from within its borders, than to control Gaza from outside of it as a prison-like entity.

Through a process of systematic demolition and armed encirclement, Israel has established a 200-300 meter buffer (the so-called Philadelphia corridor) between the entrance to Gaza at the mouth of Salah Edin Gate—the main entrance to Rafah’s central throughway-Jamal Abdel Nasser Street— and demolished entire blocks of houses in front of the gate. In addition, it has razed the houses along the borders of Gaza and Egypt—the Al Brazil Block, As Salam Block, and other make-shift residences that are simply called “Block D”—to the ground. In the Rafah camp alone, eighty children under the age of fourteen were killed by the Israelis in the process.

To put the housing demolition into some relative perspective would be say it is equivalent of 1.2 million homes in the United States were destroyed. “What the army is doing in Rafah camp is nothing less ethnic cleansing,” says Dr. Moustafa Barghouti, the head of the Palestinian National Initiative What is actually occurring is Israel’s territorial consolidation of four principles which have guided Israeli political imagination since 1968: 1) that no Palestinian state shall share any borders with any other country other than Israel; 2) a Palestinian state will have no real or meaningful sovereignty, only a functional one subordinate to Israel’s sovereignty; 3) that Israel will preserve and institutionalize the existing conditions in the Occupied Territories by protecting existing Jewish settlements; and 4) Israel will continue to build illegal settlements to create the illusion that any cessation of construction is actually a sign of Israel’s willingness to compromise and a sign of its “good faith”—a strategy that is practiced by both the Labor Party and Likkud, with the only real difference being the conservative or liberal ideology that is used to justify its ongoing colonial expansion in the West Bank. The Israeli ideological strategy has been part of a systematic process that involves four general practices: the ongoing military occupation of the Palestine Occupied Territories in general; the preservation and expansion of existing and illegal Jewish settlement in the West Bank and Gaza; the construction of new settlements (roughly a 102 new ones), and the construction of the Wall to preserve and make these practices seemingly physically irreversible realities on the ground. The function of part of the latter strategy—the building of the Wall— is as obvious as lines on the maps that represent its trajectory.

A comparison between the 1993 maps of Oslo Accords and existing plans for all three phases of the Wall incontrovertibly shows that the Wall is nothing less than the physical and concrete institutionalization of precisely those aspects of Oslo that Israel had agreed to: the establishment of tiny cloisters and pockets of Palestinian self-rule, with no meaningful sovereignty, that Edward Said compared to the bantustans which the British had devised as a means of exerting its colonial authority in Africa; it established small areas of relative autonomy with local tribal leaders subjected to Britain’s overall rule. Yet the comparisons with British form of colonial rule ends with the establishment of numerous, non-contiguous bantustans.

Whereas from 1918-1948 in British Mandate Palestine, Britain had dredged and designed the Port of Haifa, constructed six power stations for Palestinians and Jews, built public roads and buildings for everyone, all Israel has done is to shore up its military presence with more check-points, more prisons, more and expanding settlements, more rerouted irrigation systems (for the settlements), more de-development (of Palestinian infrastructure and agriculture), more barriers and more of its a massive $3.4 billion Wall.

In others words, it’s colonialism without development, or “de-development” as Sara Roy as called it, whose sole aim is the complete destruction of the foundations of all aspects of Palestinian civil society. Meaningful political resistance to this ongoing process has taken mostly two forms, the first of which is an emerging movement of a non-violent protest that has vigorously and mostly peacefully decried the wall and Israeli confiscation of Palestinian land.

As I write this there are spirited protests by agricultural workers in Marda, a village of some 2,000 inhabitants, much of whose land has been taken by the nearby Jewish settlement of Ariel, and more of which Israeli forces are trying to confiscate to build the Wall. On June 17 in Bil’in, near Ramallah and part of the Salfit area, a group of several hundred demonstrators clashed with Israeli soldiers who came to enclose more land, only to be dispersed with rounds of live ammunition fire and clouds of tear gas.

On June 7th, villagers in the town of Arab Rammadin brought bulldozers, which were razing 2239 dunams (2.2 square km) for the Wall, to a halt. In addition to these promising signs of an emerging non-violent political resistance movement, there is the often overlooked decision of the International Court of Justice, which issued its advisory opinion a year ago on July 9th, 2004. A truly enlightened decision, it is the reaffirmation of some of the most humane and principled documents of our times. It flatly put to rest Israeli’s disingenuous claims that the Wall was needed to protect Israeli security (if it were needed for that purpose, the Israeli government could have legally built the Wall along the 1967 Green Line). What was remarkable about the decision was how conceptually unremarkable it was.

The International Court of Justice

This decision provides the real possibility of legal recourse of Palestinians, who have no meaningful sovereignty, no self-determination as a state, and therefore cannot litigate its damages to a body it has historically be denied membership as a nation of people. Moreover it denied the ultimate legitimacy of the Israeli Supreme Court, whose ideals and principles lawyers like Alan Dershowitz cannot seem to live without. Indeed, the Israel Supreme Court has an impoverished record insofar as Palestinian human rights are concerned. For example, this is a court that had for years condoned torture, rarely stood up the government and military policy of detention, human rights abuses, the destruction of houses, the imposition of seemingly endless curfews, and extra-judicial assassination, and the collective denial of Palestinian human rights. In one case it valued—actually ascribed a precise economic value—-to Palestinian life. A Palestinian life was worth no more than about 5 sheckles.

The courts decision, like all other world court decisions, entails what are called erga omnes obligations that require that other signatories to the ICJ’s charter enforce and compel Israel’s compliance with its decisions: namely international agreements such as the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Conventions on the Rights of the Child, and the Geneva Convention which Israel is, in spite of its attorneys best attempts to deny its material relevance, a signatory to.

What this means in terms of the diplomatic practices of other nations remains to be seen, but it clearly opens up other arenas of resistance to the Wall that may take several forms. Nations could impose a “Human Rights Tax” on companies contracted to supply goods (bulldozers for example) and services to the Israeli governments efforts to build and reinforce the Wall, its ongoing occupation, and it expansion of existing and new settlements in the Occupied Territories. It may serve as a kind of prelude to what appears to be a growing and globally orchestrated movement to divest from Israel so long as it continues its illegal occupation and refuses to remove the Wall in its existing form. It establishes the important condition for not simply the coordinated emergence of an international human rights movement (which for years was among Edward Said’s great dreams).

All of this is to say that the ICJ decision provides the framework for developing new political and legal strategies of resistance which may take the forms of various instruments of financial, political and diplomatic pressure—boycotts, embargoes, human rights taxes, sanctions, and other restriction on the flow of Israeli capital, like the buying and selling of Israeli bonds in Canadian, European, or Asian markets. It perhaps even raises the possibility of the civil prosecution of those military and Israeli government official and those twenty or so corporations, engineers, architects, military planners, and CEOs that were and remain either commercially or politically involved in constructing, designing, planning the Wall. Indeed, the Secretary General of United Nations announced in January 2005, that the United Nations was in the process of compiling a registry of those Palestinians who had directly suffered damages—the loss of land, homes, crops, employment, etc.

While some critics saw this as the UN’s tacit acceptance of the irreversibility of the wall, the registry remains an important document in the same way that Walid Khalidi’s All That Remains provides a more or less complete material, historical, territorial, geographic and archival account of the displacing effects of 1948 War of Dispossession.

Yet whatever the Wall signifies for the precarious political and existential future of Palestinians, one thing is for certain: it is part of Israel’s willful repudiation of Palestinian existence in general and Palestinian rights to meaningful sovereignty and self-determination in particular. But it is more than that as well. It is an attempt to make Palestinians physically invisible from the experience of Israeli daily life which goes on at times as if the Wall were merely the comforting and soothing perimeter of Israeli lebensraum.

Guy de Maupassant purportedly lunched every day under the Eiffel tower. “Why?” someone asked of him. “Because,” he said, “it is the only place in all of Paris where I don’t have to look at the thing.” Perhaps the Wall, as long as it exists, will serve as a constant reminder that a large population of humanity manages by a sheer will alone to survive as a culture in a place where the sunset is no longer visible to the naked eye— except in its dreams. On the other side of the grey, storm clouds of a military occupation, there is a blue sky where the sun will always, in a matter of speaking, set—imagined or not.

Andrew N. Rubin, an assistant Professor of English at Georgetown University, is the co-editor of The Edward Said Reader and Adorno: A Critical Reader. His book Archives of Authority is forthcoming in 2006. This article was first published in Al-Ahram Weekly on July 7, 2005 and reprinted on EI with permission.

Related Links