The Electronic Intifada 27 September 2004

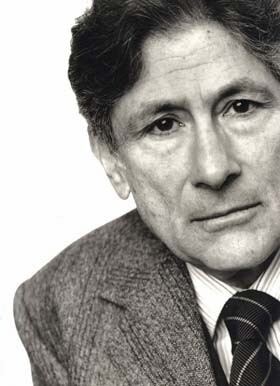

Edward W. Said, 1935-2003.

What would have happened if we still had Edward with us in this last year? This was yet another terrible year for the values Said represented and the causes he defended. We missed him as the most articulate responder to a deteriorating reality in places such as Palestine and Iraq. The only comfort is that he did not have to endure those desperate pieces of news and human vignettes flowing from Palestine and Iraq that leaves an intellectual hopeless in the face of an impending calamity.

But there is no comfort really. The prevailing sense of the last year was a haunting emptiness that accompanied the lives and actions of people like myself – the eternal observers and commentators of the Palestine scene - who have to do the job without Edward being around. We need his reservoir of associations to clarify the callousness of human kind, his sensitivities to help articulate the role of the intellectuals in such dark and sinister days and his immense knowledge of culture - in its most expanded possible definition - for putting contemporary tragedies in perspective.

Frustrating more than anything else is recalling how in the last months of his life, Said predicted/warned ominously that Palestine is lost. The Israeli atrocities, the total collapse of the West Bank infrastructure, the disintegration of law and order in the Gaza strip and the continued Arab indifference and world apathy, bit by bit made this prognostication a reality. Equally daunting was the twisted and destructive American policy in Iraq; especially when one considers it in relation to the absurd accusations made by Orientalists in the USA and Israel that Said’s perspective was responsible for the inability of the American political elite to grasp correctly the dangers of ‘Islamic terrorism’.

The state terrorism now applied in Iraq and its ruinous consequences, prove beyond any doubt, what happens if an administration ignores Edward’s admonitions against a Middle Eastern policy based on condescending Orientalist attitudes and unconditional support for Israel. The tragic events of 9/11 brought back to the American central stage the neo-conservatives and the racist Orientalists. They were quite mariginalized before, due mainly to Said’s works and activity and thanks to the brave position taken by MESA, the association of Middle Eastern Studies in the US. The only hopeful news is that in the last year saw a retraction from the fundamentalist bigotry; if not in the American media, at least in the academia.

But the last year also helped to maintain a hopeful view on the future through the writing of, and on, Edward Said. Just out were ‘Freud and the Non-Jews’ and earlier on ‘Humanism and Democratic Criticism’. This together with posthumous publication of articles and essays, and endless and most excellent symposia and workshops dedicated to Said and his works, kept Edward very much in our mind and consciousness.

If one can dare and draw a connecting thread between all that came out is the following tentative point: the disappearance of a clear distinction between the various Edwards we knew: the literary critic, the cultural philosopher, the voice of Palestine and the compass of humanism. All these fields of knowledge production come out in a mixed and blended form.

For me an assured way of disseminating abstract ideas relevant for the society at large in a more accessible and less intimidating way – the malaise of our age of post-modernity. The amazing coherence of it all comes more forcefully in the last interviews he gave and which became films watched by millions.

At a time when West End Cinemas in London were showing blockbusters – not far away from there, a long queue of people waited patiently to be admitted to a nearby cinema to watch a movie where there was only one hero, who hardly moved but whose words had the magic of gluing you to the screen more than any histrionics produced by Hollywood. It had such a power because he represented a brave struggle against his own illness and that of millions of victims of colonization, occupation and exploitation in the modern era, and he displayed a moral integrity in his insights into a world mesmerized by one dimensional media interpretation produced by the powers that be,

Edward of the last interviews was more open than before about unsolved paradoxes in his life and particularly in his work. He mused more freely about his inability to solve many of the inconsistencies that were inevitable in someone cherishing universal cultural values, respected multifarious ways of expressing them and was committed to Palestinian nationalism while abhorring by the very notion of nationalism.

The year that passed since Edward died saw the revival of the one state solution for Palestine. Even those among us who preferred the two-states’ solution for Palestine, felt in the last months that the reality on the ground in Israel/Palestine defeated this particular solution. Those of us who were committed to the Palestinian refugees’ right of return also realized, as Edward did, that a two states structure held no hope for any reasonable or feasible solution for this particular problem, the heart of the conflict and the key to its settlement. And those of us who shared Said’s universalistic approach to polity and morality can see now more clearly that before a one state solution as the embodiment of the universal values Said was searching for.

We hope, some would say hallucinate, that we can create in Palestine and Israel a space for people still loyal to elementary humanism, basic liberalism, genuine socialism or any other soft, and not dogmatic, political philosophy that strives to respect both individual and collective rights without discrimination or tyranny. And why not? One utopia envisaged by an Austro-Hungarian Jew, Theodore Herzel, ruined Palestine and its people; a new one, advocated by a American-Palestinian, inspired by Herzel’s more universalistic contemporaries, may prove the only way of rectifying these past evils and provide for a better future for everyone living in the torn land of Palestine and beyond.

Related Links

Ilan Pappe is a senior Israeli academic at the Department of Political Science and M.A, University of Haifa and the author of many books relating to the conflict.