The Electronic Intifada 7 December 2010

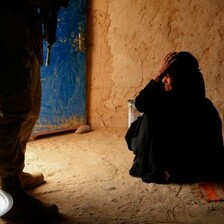

An Iraqi refugee family in Amman, Jordan, 2008. (ZUMA Press)

More than seven years after the United States and United Kingdom-led invasion of Iraq, millions of displaced Iraqis have nowhere to go. For the overwhelming majority of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs), displacement is not a one-off trauma. Rather, it is a continuous state of flight for most uprooted Iraqis, who the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates to number 1,785,212 refugees and 1,552,003 IDPs (both figures as of January 2010).

Among the Iraqis who were forced to flee their homes is a widow and mother of two, Umm Haitham, who spoke to The Electronic Intifada on condition that her real name not be revealed. “We don’t know where to go. We have nowhere to go,” Umm Haitham said, as her voice trembled over the phone.

Umm Haitham and her two children, both in their twenties, have moved three times in the past two years. To begin with, because of unbearable levels of violence they left their home in Baghdad and fled to Amman, hoping to find greater security in neighboring Jordan. “The explosions were daily, and we were living in fear,” Umm Haitham added. “But here in Jordan, neither my children nor I have the right to work. So after we’d used up all our savings, we decided to risk everything and return to Baghdad.”

When they did so, Umm Haitham and her family did not return to their original home. Thousands of Iraqi homes were occupied either by families who have themselves suffered displacement and sought shelter in temporarily abandoned buildings, or by any one of the numerous militias that have emerged ever since the invasion. Instead, Umm Haitham’s family stayed at the homes of various relatives for short periods at a time, becoming de facto IDPs.

Their story testifies to the fact that, in real life, the statuses of “refugee” and “IDP” are by no means static, while it also shows just how desperate the situation of Iraqi refugees and IDPs is. Once in Baghdad, they suffered twofold: Umm Haitham said the family was burdened both by poverty and constant fear that they could be killed any minute, adding that “the explosions were constant,” referring to the US and its allies’ bombings and the violence of the militias as well as the death squads that have emerged since the invasion and are working in collusion with the occupation. Umm Haitham’s family lost hope and returned to Amman once again, this time knowing full well how hard life would be for them there, but they hoped to at least find safety from the violence that the occupation brought to their home country.

Now, back in Jordan, they do not live under fear of death like in Iraq. Barring this difference, Umm Haitham’s family situation is still miserable. She and her children are hardly able to make ends meet, despite the fact that her elder daughter is a qualified lawyer and her son has just completed his higher education studies at a private university, putting the family further into debt which they cannot repay. Were they able to work legally in Jordan, they would probably be better off. But Jordan and Syria, which combined host the vast majority of Iraqi refugees, suffer from severe unemployment and other socioeconomic problems of their own.

“We don’t know what to do,” Umm Haitham said, unable to hold back her tears. “We have asked UNHCR to help resettle us to a country where we can work and live safely, but there seems to be no hope for us.”

According to the 2010 UN Regional Response Plan for Iraqi Refugees, “Though substantial numbers have been resettled — nearly 18,000 in 2008 and an equal number in the first nine months of 2009 — resettlement will, by its nature, be a solution only for a minority of refugees. At the same time, conditions are not yet ripe for a voluntary and sustainable return to Iraq in large numbers.” A recent UNHCR survey shows that of those who do voluntarily return to Iraq, mainly driven by the severe lack of financial security in neighboring countries, the majority regret the decision. Released in October, the survey shows that 61 percent of polled Iraqis returning to the two Baghdadi districts regret their decision because of overwhelming levels of violence affecting the Iraqi capital, just like much of the rest of the country.

According to Iraqi International Initiative on Refugees coordinator Hana Al-Bayaty, “There will be no permanent solution to the refugee crisis as long as Iraq is under occupation.” Emerging in 2003, the Iraqi refugee crisis has become one of the world’s largest, second in number only to that of Palestinian refugees.

Speaking to The Electronic Intifada, Al-Bayaty added that Iraq has been a socioeconomic entity for 4,000 years, and never, until now, had emigration been a mass phenomenon. “Even in the tragic contemporary history of Iraq, there was no migration movement. Iraqis remained despite wars and genocidal sanctions. It is only when a state-sponsored sectarian war was imposed on them — with roaming militias and death squads killing on the basis of your name and sending death threats to individual families — that hundreds of thousands fled to neighboring countries, thinking it would be temporary,” said Al-Bayaty.

Considering what Al-Bayaty describes as Iraqis’ “romantic relationship to their land and their people,” it is telling that around 15 percent of the total population is currently displaced, either within the borders of Iraq or beyond. Aside from the daily violence, mass imprisonment and torture, bombings and death threats, the US policy of dismantling the Iraqi state in order to partition the country and seize its oil resources has involved the destruction of Iraq’s public services.

“Basic goods such as food, clean water, sewage or electricity are not available,” Al-Bayaty added, noting that already in 2007 UNHCR had estimated that 40 percent of the middle class — encompassing doctors, engineers, teachers and other professionals whose participation in society makes social services possible and who oppose the occupation — had fled the country, fearing for their lives. Al-Bayaty contends that the US intended all along to destroy Iraq, and mentioned how members of the Iraqi middle class have been systematically persecuted since the very start of the war, and there is no fair justice system to fight the impunity of assassins and other criminals. In short, “there is no security and no functioning state for Iraqis to return to,” Al-Bayaty said.

“Divide and conquer”

The sectarian nightmare that has come to dominate Iraq, following the occupation’s institutionalization of a sectarian political system, is the core driver behind the continuing Iraqi mass exodus. In a country whose religious and ethnic make-up is extremely varied, intertwined and complex, the effects of the imposition of a previously inexistent sectarian political system have been murderous. Among the aspects of this system has been the bid to replace Iraqis’ overarching national identity with a sectarian, divisive identity.

This has in turn led to massive demographic changes since 2003, including mass refugee movement of groups such as Iraq’s Christians, whose numbers have shrunk from 1.4 million before the invasion to approximately 500,000 today according to the US-based Brookings Institution. The plight of Christians, whose community constitutes one of the world’s oldest and has been rooted in Iraq since Christianity’s earliest days, continues as churches are under attack, and members of the community targeted. Christians, it appears, are among the groups who have no place in the US’ distorted depiction of Iraq as a country made up of Shias, Sunnis and Kurds, a depiction promoted most heavily by the administration of former US President George W. Bush but which continues to be institutionalized to today, under US President Barack Obama’s command.

Up until the invasion and the installation of a puppet regime, political power, sect and ethnic origin had never been linked in modern Iraqi history. The invasion and the ensuing occupation changed that, with the characterization of the north as Kurdish (an ethnic group), the center as Sunni (a religious group) and the south as Shia (another religious group). This is both a glaringly wrong generalization, and a threat in itself to a country that is both ethnically and religiously diverse. Iraqis argue that the only valid identity at the political level is the national identity; replacing the national identity with a sectarian or ethnic identity is viewed as the occupation’s strategy to promote partition and therefore the destruction of the Iraqi state.

Effects on the ground of the sectarian regime imposed by the occupation include the increase of divorce and separation rates among mixed marriages as the crime of ethnic cleansing is permitted. Prior to the war, mixed marriages were by no means an anomaly in Iraq, whereas today, they are targeted. According to a report by the UN-affiliated humanitarian news agency IRIN, mixed couples had formed “an association called Union for Peace in Iraq (UPI) that aimed to protect such marriages from sectarian violence” in 2006. “Members were forced to dissolve the association after three mixed couples, including founding members of UPI, were killed,” the report added. A former member was quoted as saying mixed couples had two options: to stay and to be killed, or to leave Iraq altogether.

Though it is just one among thousands, this example speaks volumes of how the once socially mixed reality of Iraq is being replaced with a de facto partition of Iraq, resulting in mass death, mass division and a mass exodus. It appears that these three options — death, flight or acceptance of the occupation’s policies for Iraq — are the only ones Iraqis have today. It is little wonder, therefore, that so many Iraqis have fled their homes, in spite of their love for Iraq, and the difficulties they face in exile.

In tears, Umm Haitham is almost speechless as she comes face to face with the bitter reality of having lost her home. For her, like for millions of Iraqis, the country she grew up in and loved is barely recognizable today under occupation and marred with sectarian terror. Unhappy both at home and abroad, all she can do at the moment is wait. “God willing,” she sighs, “the situation will improve.” As things stand, that hope is all she has to live on.

Serene Assir is a Lebanese independent writer and journalist based in Spain.