The Electronic Intifada 5 June 2004

The New York Times did not venture the notion that a headshot is customary sniper work—that a trained professional took aim at a three year old who broke curfew—it merely happened.

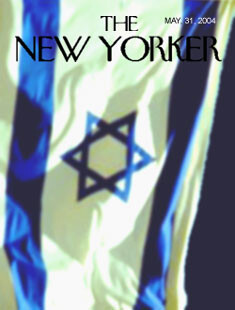

Where objectivity fails, investigative and feature-oriented journalism plays a potent role. On May 31, the New Yorker published Jeffrey Goldberg’s 21-page “Among the Settlers.” It seemed opportune that the magazine that revealed the depths of the Abu Ghraib scandal might, once and for all, do the Israeli crisis some historical justice. This is precisely why it is important to point out how it failed to do so.

To its credit, “Among the Settlers” is a long overdue exposé of Israeli settler mentality in the illegally occupied regions of Gaza and the West Bank. As wildly irrational as it is to think of an entire race as less than human, and as dangerous as it is to murder people, then raise your children on their land, people do this. Believe it or not, there is an ideology that accounts for this behavior: God said so. Let us not forget that God also told nine people to fly planes into the World Trade Center, and that He made George Bush the president. (Pity that a few crazies have to spoil God for everyone.)

To that extent, Goldberg’s ability to show, and not tell, the under-explored fundamentalism of the Middle East is remarkable. The story is bookended with a scene in Hebron where yeshiva boys shout obscenities at Arab girls (“Cunts! …Do you let your brothers fuck you?”); and Golberg’s own concluding moral, “Today, the Jewish claim to the West Bank and Gaza is one of appetite, not of starvation.” Applause to Goldberg. Few in the white liberal press would dare go there.

But the critical failures of Goldberg’s work stem from two areas: His attempts to legitimize Zionism, an ethnically exclusive colonial project, as a liberal idea; and his omission of the Palestinian right of return, which, according to the vast majority of Palestinians, is the reason there is no peace.

Under the subheading, “The Meaning of Zionism,” Goldberg outlines the founding notions of Theodore Hertzl’s Zionist movement as a “practical response of mainly religious men to the impossibility of Jewish life in Europe.” Goldberg writes that a Jewish national home in Palestine, built on the modern ideals of liberal democracy, was the answer to the rabid anti-Semitism of the late nineteenth century. Left out of this noble tale are the explicit expulsion orders of the Zionist leadership, which saw the expulsion of nearly 800,000 Palestinians during Israel’s “liberation” in 1948. Not to mention the documented massacres of Saliha (70-80 killed), Deir Yassin (100-110), Lod (250), Dawayima (hundreds) and Abu Shusha (70). Unless population transfer and genocide are the building blocks of liberal society, Goldberg’s historical premise for sanctifying Zionism is existential at best.

This rhetorical blunder could not stand on its own without the help of selective fact-checking. Throughout the piece, Goldberg frequently refers to Israel as a Jewish democracy, and states that “Arabs and Jews living inside Israel’s borders are judged by the same set of laws in the same courtrooms.” Goldberg’s careful semantics may be accurate, but his case for liberal democracy is promiscuous.

The first hit of a cursory Googling for “civil rights arab israel” reveals the Web site for the Arab Association for Human Rights. Founded in 1988 as a grassroots organization representing Israel’s 1.3 million Arabs (about 20 percent of the population), AAHR argues quite logically that Israel’s exclusively Jewish nature “overrides and compromises the extent to which it can be democratic.” The organization points out two direct forms of discrimination: any Jew and his descendents are granted nationality immediately upon immigration (Arabs have to meet a list of conditions); and Arabs cannot benefit from nor participate in Israel’s housing or settlement policy.

There are also innumerable indirect measures aimed at keeping Israeli Arabs economically immobile, thus totally ineffective members of a capitalist democracy. Among these is the Budget Law, which allocates about 50 percent less funding to Arab welfare budgets, school facilities and education programs. Additionally, Arabs, unlike Jews, are not allowed to serve in Israel’s military—doing so, after all, would mean turning weapons on one’s kindred in the occupied zones. As a consequence, Arabs are precluded from rather significant employment, housing and state childcare benefits that attend military service.

Israel has not maintained 56 years of inequality without a track record. Since the 1967 war, Israel has flouted every article of the Geneva convention, not to mention several UN resolutions. Goldberg addresses these rather outrageous matters early on—perhaps pre-emptively— by placing quotes around the word “illegal” when referring to the post-1967 Israeli settlements. He adds, “Most international legal authorities believe that all settlements, including those built with the permission of the Israeli government, are illegal.” Goldberg’s apparent take-it-or-leave-it perception of legality is journalistically dangerous: He sets himself immune to historical precedent.

By eliminating the legitimate and empirical arguments against Zionism, Goldberg leaves his readers with few moral conclusions. The direction he intends those conclusions to take is partly revealed in his omission of the most convincing anti-Zionist argument: the right of return.

On December 11, 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 194, which states the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their original homes and villages from which they were displaced during Israel’s “liberation.” Since then, Resolution 194 has been reaffirmed over 100 times by the General Assembly, and has been included in subsequent resolutions, such as Resolutions 513 (1952), 2452 (1968), and 2936 (1972).

Of course, the right of return would disrupt Israel’s closed Jewish society, as some 6 million Christian and Muslim Arabs would pour into Israel. Since Israeli Jews use only 15 percent of the land they occupy, the problem is not that there is no room for the refugees. The quandary, as Goldberg reasons himself, is that Israel would be forced into adopting an apartheid government. Zionism’s options are not terribly flattering.

If not Zionism, then what? Goldberg digs up old interviews with the late Sheik Ahmed Yassin and Abdel Aziz Rantisi, the Hamas leaders whom Israel illegally assassinated. Predictably, their commentary affirms the most rabidly anti-Jewish and Islamic fundamentalist perceptions in the Middle East.

Goldberg then turns to the Palestinian victim, Samar Hamdoun, who gave birth to a stillborn because she was denied passage at an Israeli checkpoint. “We don’t want anything to do with politics,” Hamdoun’s husband tells Goldberg. “We just want to be left alone.”

Goldberg then asks him why he had a portrait of Saddam Hussein on the wall. “He stands up for Palestinians, he fights the Jews,” is Hamdoun’s answer. The next paragraph tells us about a suicide bombing.

If you can sympathize (but not necessarily agree) with, say, a black South African villager in 1986 who said, “All white people are devils,” then you might be suspicious that Goldberg is exploiting the anti-Semitism card. (Notwithstanding the obvious contradiction that anti-Semitism, by definition, includes anti-Arab discrimination. In that regard, Zionism itself is anti-Semitic, since its current modus operandi endangers both Arabs and Jews.) Meanwhile, Goldberg conveniently overlooks the millions of Palestinians and solidarity activists who argue for the right of return, the dismantlement of an exclusively Jewish state, and the creation of an equitable, democratic society for Jews, Christians and Muslims alike.

Even where the right of return should be cited—that is, in the story’s recounting Yassir Arafat’s decision to turn down the Camp David agreement in 2000—Goldberg’s sublime, terse rhetoric fills the void: “The dispositive fact of Camp David is this: Barak made an offer, and Arafat walked out without making a counter offer.”

Ironically, the right of return offers itself in Goldberg’s story, but only in principle. Near the end of the piece, Goldberg interviews Menachem Froman, a rabbi who lives in Tekoa, one of the illegal settlements in the West Bank. Froman believes that the West Bank should become Palestine, and that he would gladly become a Palestinian citizen if it did. He says:

I’m a realist. I accept reality. I’m not talking about utopia. I accept what I see. There is a Tekoa and a Tuqua.

And Goldberg’s editorialized rebuttal: “Froman is naïve to believe that the Palestinians would accept [him].” If Goldberg had properly researched the right of return movement, he couldn’t make that dismissal. Maybe he just ran out of room.

Zachary Wales is an activist with the New York Chapter of Al-Awda, the Palestinian Right of Return Coalition. He moved to New York in October 2003 after working in Namibia and South Africa for four years as a media research consultant and news correspondent.

Related Links