United States 30 July 2006

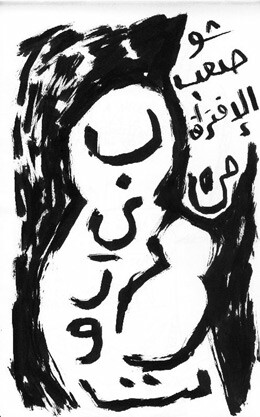

“How difficult is the separation from Beirut” by Mazen Kerbaj. View more of his work.

When war began in 1975 I chose for practical reasons to stay and fight. When I say ‘fight’ I mean fight in a way a housewife does. As the keeper of the hearth you are the heartbeat of your family. You are the mother who comforts her children after a bomb blast shatters part of their bedroom wall. You are the wife who consoles her husband after he has spent his mornings treating wounded civilians and sending mangled bodies to the morgue. Collectively, you are the pulse of a country on the verse of collapse.

As I witness the devastating scenes from Lebanon today I realize that my daily struggles for survival during the civil war were, by comparison, trivial. Then, I had only to deal with such things as water shortages. I washed my clothes in the wee hours of the night when water finally began to flow. I filled buckets for doing dishes, watering plants and flushing toilets. I found ways to mount the power outages.

My children finished their homework by candlelight at the kitchen table while I prepared the evening meal. Flashlight in hand, I descended eight flights of stairs to walk the dog. In spite of a night-long battle in my street, I had my children dressed and fed in time to catch the school bus at 6:45 a.m. And when schools closed because of war — sometimes for months at a time — I hired a tutor to keep my children’s minds usefully occupied.

When my apartment took a direct hit I had only to repair the damage. When my car, parked on the street below my apartment, got sprayed with shrapnel, I was grateful the bullets had not punctured my engine and I was still able to drive. When an opposing militia tried to muscle its way into our neighborhood, I adopted a kind of psychological ownership of my street when my husband joined the militia and took up arms.

Women in South Lebanon and in the southern suburbs of Beirut are the unsung heroes in the struggle to survive the most recent Israeli aggression. They have no water, not even drinking water for their children. Out of desperation, they resort to using sewage water polluted by phosphorous bombs and depleted uranium, weaponry outlawed by international law.

They have no homes left. Their dwellings were targeted for destruction by the mightiest army in the Middle East because they were suspected of housing Hezbullah fighters.

If their homes have resisted the repeated bombing raids, they have no electricity, no water to flush toilets or do the dishes. This, of course, implies that they have food to feed their families and gas canisters to power their stoves. Many are too poor to own cars and do not have the money to hire a taxi to drive their family to Beirut.

If they do have cars that have not been destroyed in a bomb blast, they still cannot leave; they have no gas to travel to a safer refuge. If they are able to obtain gas, they fear driving the few routes left out of the south because the Israeli army refuses to guarantee them safe passage, even though they just dropped leaflets on all villages in the south ordering the residents to leave.

Many women no longer have families. The remains of their children and husbands were pulled from the rubble of an Israeli-bombed building just a day or two ago. They were obliged to identify what they could of the body parts and the shreds of bloody clothing of their loved ones strewn around the bombsite. The trauma, the desperation, the grief and daily massacres of family and friends are more than they can endure, more than any human being should ever be expected to endure.

Standing with the women of Lebanon in their moment of agony is the highest form of solidarity I can think of and also the only meaningful form of defiance and resistance to Israel aggression. I regret that I am obliged to do this from so far away.

Related Links

Cathy Sultan is the author of A Beirut Heart: One Woman’s War (Scarletta Press, October 2005) and Israeli and Palestinian Voices: A Dialogue with Both Sides (Scarletta Press, April 2006). She can be reached at cgsultan@charter.net