BBC 7 May 2003

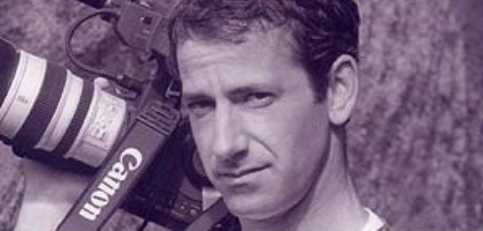

James Miller - “His likes will not be here again”

James Miller is dead. I need to say it aloud because I cannot quite believe it. This laughing, mischievous, supremely talented and decent man is gone.

My wife gave me the news and she had tears in her eyes. This was because we both had the pleasure of spending several days with James a year ago in Istanbul.

She, like me, remembered the kindness and warmth, above all the patience, he showed to our six year old son.

James Miller was one of the finest journalistic talents I have ever known. Had he lived he would undoubtedly have come to be recognised as one of the greatest documentary makers of his generation. As it is he leaves a journalistic legacy of immense worth.

After first working as a photographer he began his television career with the “Frontline” agency in 1995. I first met him in Algeria where, with typical bravery, he was reporting on that country’s vicious civil war.

He reported from most of the major trouble spots during the last decade but he was never gung-ho or one of the war junkie brigade. He was a thoughtful and sensitive journalist who went to these places in search of essential truths.

James had worked for all of the major news broadcasters in Britain as well as CNN. At the time of his death he was making a film for the cable network HBO in the US. He was one of the team which made Prime Suspect, a film on war crimes in Kosovo which won the Royal Television Society prize for Best International Current Affairs Programme.

Whether it was reporting on the death squads of Milosevic or the Russian bombing of a refugee convoy in Chechnya, James always placed the rights of the vulnerable at the top his priorities.

It was in the last two years that James’ talents brought him international acclaim. Together with reporter Saira Shah he produced the groundbreaking film on life under the Taliban “Beneath The Veil”.

James and Saira became the golden team in international current affairs journalism. It is a measure of the respect in which they were both held that the avalanche of awards they received was greeted with genuine pleasure by friends and competitors alike.

Their work in Afghanistan won them, among others, two Emmys, several Royal Television Society awards, a BAFTA and a Peabody.

I worked with James on a documentary about the genocide of the Armenians in Ottoman Turkey. From the outset James’ attitude was robust.

He had no personal animus against Turkey or the Turkish people, but he was determined to ask the tough questions and use, where the facts warranted, tough language.

James believed in unambiguous truth telling and would never have compromised in the face of official disapproval or attack.

I referred at the outset to his sense of mischief. He was a dangerous man to sit near during any encounter with a bore or a pedant. Once in the middle of a spectacularly tedious interview he caught my eye - James was sitting directly behind the interviewee - and smiled.

Then he began to giggle. In a few seconds he was rocking with silent mirth. I naturally dissolved into laughter myself, frantically trying to cover it up by developing a coughing fit. The interviewee was - like all good bores - totally unaware of our discomfort.

On the road we talked often about the pressure of our jobs on those we left at home. When James spoke of his wife Sophy (she was then expecting their second child Lottie) and son, Alexander, there was deep warmth in his voice. I simply cannot imagine the anguish being experienced by his family.

On that night in Istanbul we went to the waterfront and sat upstairs in a restaurant overlooking the Bosphurus. My son Daniel attached himself to James. I suspect he sensed a “soft touch”, someone willing to play games and tell stories.

When it came time to go home my boy insisted on travelling with James in his car. When he woke up the following morning he was looking for James. We have a saying in the Irish: ni bheidh a leitheidi aris ann. It means “His likes will not be here again”.

Related Links: