Balata refugee camp, Palestine 15 December 2004

The Huwwara checkpoint is closed to internationals. The entire Nablus region is completely off-limits. Our destination is the Balata refugee camp on the outskirts of the city, where Palestinian resistance to the Israeli occupation is said to be the strongest in the West Bank. One British journalist told me that Israeli military strategy is to keep foreigners from entering, flood the area with troops, then “turn the lights out”.

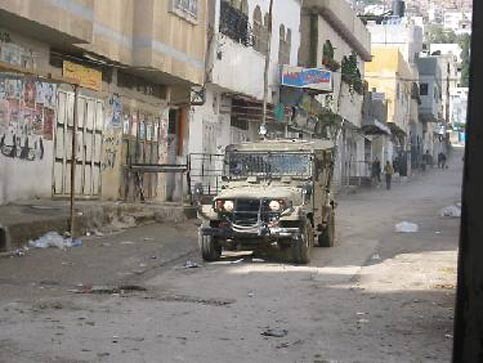

We are met by a van and driver who takes us around the checkpoint then leaves us at the side of a nearby mountain road. He tells us to hurry up the trail, then drives off quickly in order to avoid being seen by Israeli forces. After a short hike we are met by another van and driver who takes us off-road, then to Balata, avoiding an army jeep blocking the road ahead.

Soldiers attempt to enter the camp from alleys and side roads hoping to draw out resistance fighters into clashes in streets crowded with children who are not in school. Sound bombs, tear gas and live ammunition are used to quell the opposition; although it became clear to me after only a day in Balata that every incursion and every shot fired adds to the resistance.

Tear gas lands in the UN water compound, on top of the mosque, and on top of the ambulance. Local boys with the accuracy of major league pitchers land rocks, bricks, cinder blocks, sticks, and even bags of garbage upon the Israeli vehicles, pock-marked from the direct hits. Children run through the streets with life-like toy guns. It’s a wonder more children are not killed.

Martyr posters — often in layers — cover the shops and walls of Balata as if telling the locals of new movie releases. The newest poster shows the 16 year-old suicide bomber from nearby Askar camp who blew himself up in November at a market in Tel Aviv, taking out three Israelis with him. I visited the boy’s family only days after the incident, and the parents spoke of how — only hours after hearing the news of their son — the Israeli army demolished their home, arrested his three brothers who had no involvement, then killed a 12 year-old boy.

The past few years has seen the addition of female suicide bombers, including a 20 year-old woman from another Nablus refugee camp only 3 months ago. I was told many times that these “victims of the occupation” died for the resistance and are even now sitting alongside Yasser Arafat as Palestinian martyrs. The military base only minutes away from the Huwwara checkpoint likely means another layer of posters.

In a couple of short weeks in Nablus the casualty list at the hands of Israeli soldiers is long:

-15 year old boy killed

-16 year old boy killed

-local political leader assassinated

-14 year old boy shot

-home firebombed

-shops demolished

Despite the constant presence of the military, the residents of Nablus take time to show solidarity with the people of Fallujah, victims of another occupation. On more than one occasion an American human rights activist found it easier and safer to tell Palestinians he was Canadian, as opposed to explaining in broken Arabic… “I voted for Nader”.

From the north we received a call that some families outside the city of Jenin (with its own bloody history) could not harvest their olives because of being attacked and fired on by soldiers at the edge of an illegal Israeli settlement. The family we worked with had already seen their home destroyed several times and their olive trees uprooted by the military. Our presence drew warning shots and visits from troops, but the family managed at least to harvest a few hundred kilos from their trees… likely for the last time, as the “security fence” is nearly completed. In this settlement there are more soldiers than residents, as we’re told that Israelis are afraid to move into areas such as Jenin because of the recent conflict. But the settlement stands.

As a child protection social worker I met with several community groups to explore the reality of being a young person in the West Bank. On one occasion in Balata I asked how the Israeli occupation impacts the youth. Here are the top three answers given:

1. It kills them

2. It injures them

3. They go to jail

Balata is a place where stereotypes are shattered. Shattered and found on the road alongside tear-gas canisters and broken bottles. Balata is a place where many residents still hold keys to their homes only a 30-minute drive from the camp, but 50 years ago, and more displaced than ever.

Despite the anger and mourning there is still hope in many of the voices I heard. “We don’t want to be occupied anymore than the Iraqis do. We don’t want a wall. We want peace. Listen to what the world is saying”.

Thomas Feakins is a Canadian Social Worker and human rights activist from Vancouver. He spent the month of November 2004 in the West Bank areas of Nablus and Jenin with the International Solidarity Movement.