The Electronic Intifada San Francisco 17 September 2012

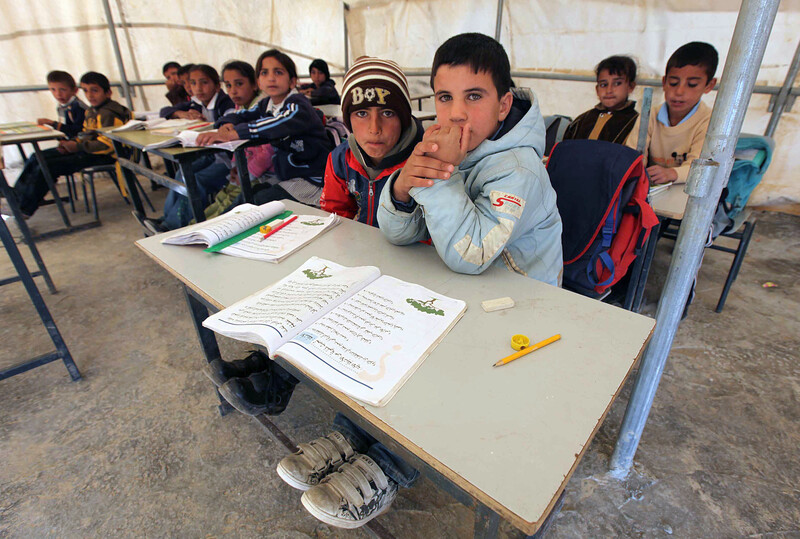

Bedouins are deprived of proper education facilities in both the West Bank and the Naqab desert.

APA imagesNine years after being “recognized” by Israel, the Bedouin village of Abu Tulul opened the doors of its first secondary school on 27 August.

Situated in the Naqab (Negev) desert, Abu Tulul is home to 12,000 Bedouins, 2,600 of whom attend junior high school. It is one of a handful of “recognized” villages amid a vast expanse of Bedouin communities that remain “unrecognized.”

Since the village was granted “recognition” in 2003, residents and civil rights organizations have been fighting for the establishment of a high school. Campaigners believe the presence of a school is required to curb the high drop-out rate that has become endemic in Bedouin communities. Fifty-five percent of Bedouin students drop out at high school age compared to an Israeli national average of just 4.6 percent. For female students, the trend is worse: 77 percent of Bedouin girls drop out in their high school years.

Eight Bedouin villages of the Naqab were “recognized” in 2003 as part of the Abu Basma Regional Council. Under the leadership of Ariel Sharon, Israel’s Ministerial Committee on the Non-Jewish Sector promised in 2005 that 470 million shekels (almost $121 million) would be invested in the Abu Basma localities over the course of three years in order to develop education, health and other social services (“Off the map: Land and housing rights violations in Israel’s unrecognized Bedouin villages,” Human Rights Watch, March 2008 [PDF]).

But the government never delivered.

All in all, the Abu Basma Regional Council received a meager 574,000 shekels (approximately $147,000), a fraction of what was originally promised. As a result, “recognized” Bedouin communities have little more public services — including running water, roads, and schools — than their “unrecognized” counterparts.

Despite an Israeli high court ruling in 2007 that ordered the education and interior ministries, as well as the Israel Land Administration, to build and open a high school in Abu Tulul by September 2009, students remained deprived of basic educational facilities.

In September 2009, Adalah, a group campaigning for the rights of Palestinians in Israel, petitioned the high court over the ministry of education’s failure to establish a secondary school (“Demanding implementation of Supreme Court decision ordering the opening of the first high school in Arab Bedouin unrecognized village of Abu Tulul in the Naqab,” Adalah, September 2009). The petition was submitted on behalf of 35 female students and local organizations.

Adalah’s petition argued that the ministry of education had breached the rule of law by flouting the 2007 high court ruling and that it was denying the right to education of children.

The Electronic Intifada contributor Charlotte Silver interviewed Sawsan Zaher, an attorney for Adalah.

Charlotte Silver: Why had the municipality failed to open a school in Abu Tulul? Did the fault lie on the local or national level?

Sawsan Zaher: Abu Tulul is a Bedouin village that was recognized by the state in 2003 but is still under planning process. The education issues fall under both the local council and the central (national) government, the ministry of education. The authorities argued they cannot establish a school as long as the planning process of the village is not finished. To note, the planning process started in 2003 and until today has not been finished.

Due to our petition we succeeded in making them finish the planning of the school area so that we did not have to wait for the end of the planning process of the entire village.

CS: Talk about the consequences of not having a high school in Abu Tulul.

SZ: Not having a high school is illegal and constitutes a breach of the state’s duty to provide education equally for all citizens; it violates constitutional rights of the pupils, their right to equality, dignity and mainly education; many of the pupils were not able to continue their education for lack of school; the pupils that continued were obliged to travel to other far-away villages to get education; [and] the percentage of drop-out from school was high, mainly among girls — since traveling to other schools in other villages obliged them to take transportation that was mixed with girls and boys, and many girls were not allowed due to strict social norms to take this transportation.

CS: Where would students go for school?

SZ: They would go to other recognized villages, which were far from their houses and made the commute very long for them.

CS: Are there other villages in Israel facing this kind of lack of resources and basic public services? Are there other cases of a similar nature that Adalah is fighting?

SZ: Yes. Most of the villages that have a similar status to Abu Tulul — 11 in number — face similar issues. In addition, all the 36 unrecognized villages face more severe problems because they are not recognized at all and thus there are no planning processes for them. Meanwhile, we don’t have other pending cases in court related to establishment of schools.

CS: Your petition was on behalf of 35 girls. Why did Adalah choose to make this a case about gender discrimination instead of a general right to education?

SZ: Although the petitioners were mostly girls, the petition includes all possible arguments, including and mostly the right to education. But it was important for us to illustrate the gender aspect because of the crucial impact on girls since their drop-out rate from high school was huge and got to 77 percent due to lack of the school.

CS: When Israel grants a village recognition, what is supposed to happen. In the case of Abu Tulul in 2003, what did and did not happen?

SZ: They didn’t go forward with the planning process and they dragged this process for years. Though it [Abu Tulul] has been recognized since 2003, they still haven’t finished the process. In Jewish places such a process can take a much shorter time, in some cases as little as one year only.

CS: Have you seen this sort of negligent delay in other cases involving Palestinian citizens of Israel?

SZ: Yes. This happens a lot with regards to the Bedouin villages, mainly those which are not recognized. This is used as an excuse to not provide any essential services such as education, health, water, electricity or welfare services arguing that there is no planning process. The state has also been saying that they are not providing these essential services in order to put pressure on the Bedouin residents to evacuate their land and move to villages that were set up by the state. Unfortunately, this argument has also been justified by the [high] court.

CS: How does Israel inhibit education to its Palestinian minority and poor citizens in other ways?

SZ: Among other things, discrimination in budget allocation; supervising the appointment of principles and teachers; severe supervision of the curriculum so as not to include the Palestinian history; lack of resources such as classes, laboratories and others; [and the] lack of representation of Arabs in decision-making processes related to the education system.

Charlotte Silver is a journalist based in San Francisco and the West Bank. Follow her on Twitter at: @CharESilver.