The Electronic Intifada 1 February 2017

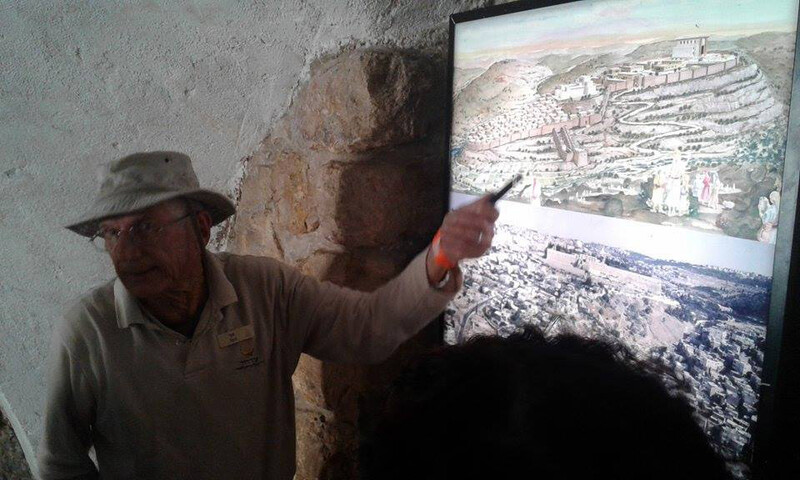

Tzvi, an Elad tour guide, delivers a highly selective history of Jerusalem.

The so-called City of David is a leafy promontory, running out from the southern wall of Jerusalem’s Old City to bisect the Palestinian community of Silwan. The tourist trap and archaeological site is moments from the Western Wall, the Haram al-Sharif and al-Aqsa mosque.

On a map near the site entrance, the City of David itself is picked out in bright colors. Surrounding Palestinian neighborhoods are faded by comparison. Another sign near the doorway, which was surrounded by Israeli school children gobbling packed lunches, claims tours are run by “local volunteers.”

It neglects to mention that these “local volunteers’” are part of the extremist settler organization Elad. They are not drawn from the Palestinians who live in the area.

Elad – a Hebrew word which means “God’s eternal faith” and is also an acronym for “To the City of David” – has full control of the site. As the site expands under flimsy pseudo-archaeological pretexts, Elad is able to demolish Palestinian property and infrastructure and drive Palestinians from their homes, in collusion with state authorities and backed by Israeli police muscle.

Elad’s City of David is largely built on land seized from Palestinians under the absentee property law, a 1950 directive that allowed the Israeli state to take over Palestinian property if owners were not present – because they were either abroad, as absentees, or elsewhere in Palestine as “present absentees” – following the violence that led to the creation of Israel in 1948.

After Israel occupied East Jerusalem in 1967 and unilaterally annexed the area – an annexation not recognized by any other country – all Israeli laws, including the absentee property law, were extended to the city.

And each year, 400,000 visitors to the city are exposed to Elad’s highly selective, ethnocentric version of history, privileging Zionist claims to Palestinian land.

Blink and miss millennia

Thus it was that half a dozen American tourists, both Christian and Jewish, congregated at the entrance for a tour in November. As they chatted, a muezzin sang out the call to prayer from al-Aqsa mosque, just up the hill.

Clad in colonial-style khaki hat and shorts, tour guide Tzvi squatted as he introduced himself to the group. “Our story starts 3,000 years ago, when Hebron tribes asked David to be their king,” he began. “Democracy! We invented it.”

As Tzvi told it, Jerusalem “did not belong to any tribe” when David is purported to have sacked it in 1,000 BCE. While conceding a Canaanite civilization was present in the city – referring to them as Jebusites, as per scriptural tradition – he says they were “not important.”

“I’m thinking maybe God told him to take it!” chirped a tourist. No mention was made of the city’s foundation back in 3,500 BCE, or the subsequent centuries of Bronze Age civilization.

The tour moved into a 3D presentation, with a 1950s educational filmstrip vibe. A holographic architect hosted the show, glancing up from a relic to feign stagey surprise at the tour’s arrival: “Oh! Hello there!”

Animated Israelite soldiers crept up a water tunnel to capture the city, a version of events with no basis beyond a single line in the Bible, but presented here as fact. “A city with no justice loses its right to exist,” the host intoned, as Biblical narratives played out on the screen.

Following Emperor Hadrian’s murderous purge of the city’s Jewish population in 135 CE, the presentation abruptly skipped over nearly 2,000 years. It did not cover later Roman and Persian rule, Jerusalem’s conquest by the Arab Caliphate in 638 CE, or 14 subsequent centuries of Islamic life.

Also ignored were the Crusades, Jerusalem’s Christian history, and the Ottoman Empire. Blink once and Jewish families were arriving in the late 1800s: blink twice and it was 1990, with a “re-established Jewish community” in the area.

“We have returned to the hill where it all began,” concluded the digital archaeologist in strident tones, as pictures of 20th century Israeli landmarks flashed up. “Boys and girls are playing in Jerusalem’s streets once again.”

Bible in one hand

The tour group emerged into the light. From a look-out at the highest point of Elad’s City of David, the presence of Palestinian boys, girls and whole communities could not be glossed over.

“When David came, nothing was here,” Tzvi claimed, as he pointed at a vast, ramshackle bank of Silwan houses immediately to the east.

“That’s an Arab village which is actually part of the municipal area of Jerusalem. There are more than 20 Arab villages within Jerusalem.” He chuckled. “Did you know that?” There was a chorus of coos and snapped pictures.

Next, the tour moved down into the excavation itself. Despite being indicted for “damaging antiquities, wilful destruction, and the disregard of court orders,” Elad was handed full control of the site by the National Parks Authority in 1997. (Elad-funded workers have also been accused of destroying Islamic archaeological finds.)

An ongoing dig at the City of David site.

This is the digging ground of Dr. Eilat Mazar, an archaeologist whose say-so is taken as gospel by Elad, and who claims to have uncovered King David’s palace here in 2005. “I work with the Bible in one hand and the tools of excavation in the other,” she has said.

“Dr. Mazar brought some arguments, I won’t tell them all now,” Tzvi said. Appealing to the religious crowd, he showed off seals apparently bearing the name of an Old Testament official.

Mainstream Israeli archaeologists are highly skeptical of Mazar’s claims. “Had it not been for Mazar’s literal reading of the biblical text, she never would have dated the remains to the 10th century BCE with such confidence,” prominent critic Israel Finkelstein of Tel Aviv University has said.

But such commentary is dismissed almost with sadness here.

“Some people say if archaeology doesn’t prove something, then the Bible must be wrong, it’s just stories,” said Tzvi, shaking his head. “But not all archaeologists are evil.”

“The more they search, the more the Bible’s going to be proved,” a tourist said happily. “Some want to disprove, and some want to prove.”

Wasteland, maybe

An Israeli flag hangs from a home taken over by settlers in the heart of Silwan.

The group then waded through the trip’s main attraction, a navigable subterranean waterway known as Hezekiah’s Tunnel, and damply emerged for a final Q&A session.

When asked who exactly had built on top of the site in the intervening two millennia of history, Tzvi grew cagey: “Here was nothing. Wasteland, maybe. I don’t know.”

His answer neatly encapsulated the deliberate omissions at the heart of these tours. Credulous tour-takers swallowing Elad’s narrative will leave with the sense Jerusalem stood empty for centuries until Zionist settlers returned to reclaim it. The constant Arab presence encompassing centuries of culture, conflict and religious tolerance is ignored.

And nor do the tours cover what is happening around Jerusalem today.

Sahar Abbasi works in the Wadi Hilweh Information Center, a community organization whose modest offices stand in the shadows of Elad’s City of David.

Here the focus is vastly different and the concerns acute. “We are not talking about history or heritage: we are talking about compulsory transfer,” Abbasi told The Electronic Intifada.

Elad’s aim, stated explicitly in 1998 and evident in practice ever since, is to “Judaize East Jerusalem” by driving out Palestinians and parachuting in Jewish Israelis. Settler homes draped in Israeli flags stud Silwan, their Palestinian owners often forced out by Elad’s exploitation of Israel’s discriminatory absentee property law.

These transfers are illegal under the Fourth Geneva Convention, which forbids occupying powers from transferring its civilians into occupied territory.

Others have been forced to leave their homes to make way for the dubious expansion of Elad digs. (Even Elad’s favorite archaeologist Mazar has slammed a recent City of David excavation as a “tourism gimmick” flouting good archaeological practice.)

Targeting the locals

The destruction of land and community centers in Silwan is also directly linked to Elad’s City of David and the wider Jerusalem Walls National Park, in what Abbasi called a “well-planned, systematic agenda” of expansion.

Elad is abetted by the Israeli state, which systematically sells the organization occupied land at rock-bottom prices.

More broadly, Abbasi linked the arrests, beatings and violent abuse suffered by Silwan’s children to the loss of land and livelihood driven by Elad. The group operates in collusion with Israeli militarized forces.

In 2010, Elad chief David Be’eri ran over two Palestinian children during a rock-throwing incident in Silwan. Both survived.

“[Demolitions] are a municipality job, but still we find Nature and Parks Authority people there, Elad people, all being protected by police and soldiers,” Abbasi said. (Elad also runs special tours for Israeli soldiers.)

Muhammad Ja’abees had to destroy his own home, leaving him and his children without proper shelter.

As with an estimated 20,000 Palestinian houses in East Jerusalem, Muhammad Ja’abees was unable to secure municipal permission to build his home thanks to tortuous Israeli planning regulations targeting Palestinians. The unemployed 32-year-old, whose house was a five-minute drive from the City of David, was forced to destroy his house with his own hands in November 2016 rather than pay an expensive and cruel fee. It’s a common tactic employed by Israeli officials.

“The municipal authorities kept trying to pay me off [by purchasing the house] and I said no, no,” he told The Electronic Intifada. “Eventually they said I was going to pay.”

He and his preschool-aged children now sleep rough under a tarpaulin amid the rubble of their former home. Though not directly at the behest of Elad, the demolition formed part of the campaign of Judaization the settler organization is pushing in the area.

“I had to destroy my own home,” he said. “And [doing so] destroyed me.”

Thou shalt not bear false witness

Elad’s City of David National Park is only minutes from the wasteland where Muhammad’s family huddles at night. But few of the tourists it hosts will ever see the destruction Elad wreaks in Palestinian communities.

Alongside ticket sales from its massive tourist franchise, which encompasses similar archaeological experiences and tours across East Jerusalem, Elad rakes in more foreign donations than the seven largest left-wing Israeli nongovernmental organizations combined. Some of this cash is being used to build a gleaming new visitors center, standing seven stories high.

Palestinian businesses have been demolished and archaeological sites placed at risk to create an air-conditioned walkway conveying tourists from the Old City to the City of David without the risk of meeting a Palestinian.

Elad’s sphere of influence is expanding: it recently won control of the Jerusalem Archaeological Park, alongside the Western Wall plaza in the heart of Jerusalem’s Old City.

Unchallenged, Elad’s ethnocentric revision of history will continue to legitimize Israel’s illegal occupation of East Jerusalem in the eyes of millions of tourists.

“We brought many important laws to the world,” Tzvi told his visitors that November day in Elad’s City of David. “Who knows the ninth commandment? It was my mother’s favorite. Don’t tell lies, ever.”

All photos by Matt Broomfield.

Matt Broomfield is a freelance journalist currently working in London. He regularly reports for The Independent and writes for VICE, Dazed and activist media, as well as publishing poetry and fiction.Twitter: @hashtagbroom. Website: mattbroomfield.contently.com