The Electronic Intifada 24 October 2025

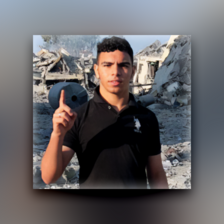

Ziyad Bhar, left, and Muhammad Bhar, right, were killed by an Israeli drone strike on 25 September 2025.

The last time that I saw my uncles Muhammad and Ziyad Bhar was in August 2023, at a goodbye gathering for Muhammad’s son Mohsen, who was going to work in the United Arab Emirates as a chemistry teacher.

We gathered at Uncle Muhammad’s home in al-Bureij and exchanged stories, food and laughter. As he always did, Muhammad walked my family to our car, hugged us in his warm embrace and told my father to take care of my mother.

On 25 September 2025, my uncles Muhammad and Ziyad, 68 and 66, were killed by an Israeli drone strike in Nuseirat, central Gaza.

Also killed were my cousin Muhammad Bhar, 34, and Ziyad’s son in-law, Tareq Zaqout, 33. They had been on the roof of their four-story home, preparing food for the rest of the family.

“Their bodies were torn, barely put together,” my younger brother Ahmad told me over the phone. “The shrapnel tore their flesh all the way to the other side.”

His tone, though sad, was one that impressed on me that he had grown so used to death.

Ahmad and my mother, Nehad, had been on their way to visit Muhammad and Ziyad the same day of the massacre. They then changed their destination to a hospital in Nuseirat, where my uncles’ bodies were laid.

My mother shrieked at the sight of her brothers’ and nephew’s bodies. Her feet trembled, and she fell to the ground.

“Please stand up, please!” she cried over their bodies.

As she couldn’t stop crying, Ahmad walked my mother outside for a breath, but even then, Ahmad told me she couldn’t stop weeping.

My mother, who is about a decade younger than her brothers, grew up in al-Tuffah neighborhood in Gaza City.

She told me how she would wait for all her siblings to gather at the dinner table before she began eating, as that was her favorite time with them. They would tease their parents and joke with each other, joking that their father should take a second wife so their mother could get some rest.

Uncle Muhammad also wanted to get a cat, but my grandmother refused, scared her couches would get ruined. Yet Muhammad said that she need not worry about the cat liking the couches too much, as even the cat would have back pain from them.

My mother was the sister who they came to for advice and care. When their mutilated bodies were placed before her eyes, still and lifeless, it must have been as though her soul was straining to reach theirs.

“You forgot your brother?”

Out of four brothers, Muhammad and Ziyad were the closest.

Ziyad’s son Muhammad, who was also killed that day in Nuseirat, was both named after the prophet and because of Ziyad’s love for his older brother. The families spent the genocide together, and Ziyad warmly welcomed them to his home in Nuseirat in the first months of the genocide, as Muhammad had to evacuate al-Bureij.

My parents and my brother Ahmad joined them later in the genocide.

During that time, they fought together against hunger and displacement. They gave my mother heavy blankets in the winter, and they shared their clothes and mattresses.

They were generous, especially when it came to family. That’s how I always knew them.

Growing up, I used to spend most of the summer at their houses in Nuseirat and al-Bureij.

Uncle Muhammad had a little farm with chickens, ducks, doves and many stray cats, which he used to feed. Whenever I craved chicken or duck, he would slaughter one of his and make a meal for me and the family, a habit he continued till the end of his life.

Muhammad had eight children, and he treated me as his own son.

He was once a chef and had opened a shawarma restaurant, though he had to close it for financial reasons. But this explained his love of cooking and his spectacular preparations of mandi (a yellow rice dish, often with chicken cooked in the earth) and shawarma.

He made the best chicken mandi whenever my family visited. When it had become too long between visits, he would say to my mother, “What? You forgot your brother? Tomorrow you have to visit me.”

His generosity never faded.

The muezzin and the designer

Uncle Ziyad’s presence was peaceful and calm. He was patient.

I don’t recall him raising his voice to anyone in my life.

I never had to worry about conversation whenever I sat next to him. I was just comfortable.

My mother used to tell me that I had some of his traits.

Spending his free time at the mosque, Ziyad memorized the Quran and was later the muezzin at his local mosque, issuing the call to prayer throughout the day.

Ziyad finished his bachelor’s degree in the 1990s and worked hard all his life. Upon retirement, he used his savings to build apartments for his sons so they could establish themselves and get married.

He was a father of eight and a grandfather of 14. He loved his grandchildren and was so excited for his son Muhammad to get married.

Yet Muhammad never got married.

In 2017, after obtaining his college degree, he opened a printing and design business called Bhar Printer. As cousin Muhammad and Ziyad struggled to cover the costs of the business, Uncle Muhammad stepped in, unasked, and provided help.

Cousin Muhammad was passionate about computers and design. Soon after we would finish playing football in the street with his younger brother Motaz, Muhammad would run back to his computer.

I recall his disappointment and the momentary frustration whenever the electricity was cut off.

The pandemic led to the closing of Bhar Printer. In debt, Muhammad struggled to pay back loans and also save for his marriage.

Right when Muhammad had saved the right amount to get engaged, the genocide began. A few families rejected his marriage proposals during the genocide due to his financial situation.

Muhammad had a kind soul and wanted to love and be loved. His kind smile lingers in my memory.

Miserable final years under genocide

Before they were massacred, their souls were tormented during the genocide.

Uncle Muhammad’s son Mahmoud, a father of two, was shot in the head by a sniper in Rafah on 15 August 2025. He had been going to get flour for the family at a so-called safe distribution point.

Uncle Muhammad also lost his farm and home to Israeli attacks.

Ziyad was longing to help rebuild his neighborhood’s mosque, so he could announce prayer again.

In their last forced evacuation from the north to the south on 20 September 2025, I suggested to my family to go back to Uncle Ziyad’s, cover the roof and shelter there. My family, though, ended up staying at another place in Nuseirat, thus avoiding the fates of my relatives.

My heart bleeds for my uncles and cousin, and then sinks again, as if I’m falling into a void. It is even more painful to imagine that my mother, father and brother could’ve been there.

I dream that I am crying, to the point that I cannot take a breath.

Every day, I open the WhatsApp news chat and scan for news. The bombings have not stopped, and people are still being killed by Israel.

I don’t know all of their names, what they were like or how many loved ones they had. I only see a number.

Scrolling in pain and anger, I feel that a part of me is killed with every martyr.

I never knew Tareq, who was killed that day on the roof, but I know he had two children and a loving wife who will miss him forever.

My family and my people don’t deserve this.

The author is a writer from Gaza.