The Electronic Intifada 22 January 2007

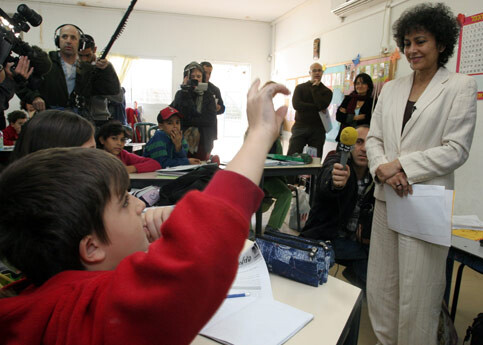

Amnesty International’s Secretary General Irene Khan visits the only bilingual school in Jerusalem, where classes are held in both Arabic and Hebrew simultaneously, 7 December 2006. (MaanImages/Magnus Johansson)

The current public education system in Israel mirrors the wider divisions in society. It is divided into separate sectors: religious Jewish, secular Jewish, Orthodox Jewish and Arab. Although roughly one quarter of Israel’s 1.6 million schoolchildren are Arab, their parallel education system reveals fundamental inequality. The 2001 Human Rights Watch report “Second Class: Discrimination against Palestinian Arab Children in Israel’s Schools” details the extent of the inequalities in funding, facilities, teacher-student ratios.

Integrated schools represent a glimmer of light in this picture of a discriminatory and segregated education system.

Integrated schools provide a neutral space where the children of fractious and opposing groups can be educated together. Their model reflects the widely held belief that “contact” between people and communities will improve relations. Contact opportunities fall into two distinct categories — the short-term and largely symbolic, and the longer-term and sustainable focused. Too often, interventions facilitated by well-meaning international or local NGOs in Israel fall into the first, superficial category. Joint Arab-Jewish projects to clean up the polluted River Jordan, the replanting of olive groves and one-off theatrical events all fall into the first, more symbolic category. Although not without value, they are too often the window-dressing the Israeli and international communities present to show that something is being done to “break down barriers” and “reduce prejudice” amongst young people.

In contrast, integrated schools offer an opportunity for the sustainable contact that is critical if lasting relationships between the two groups are to be built. The Arab and Jewish children who attend the four bi-national and bilingual schools in Israel supported by the Ministry of Education, do so every day, year in and year out. Similarly, the parents, teachers and administrators involved with the school are in constant contact; in this way the communities are drawn together through their children.

But do the schools deliver on the opportunity to build bridges between the two groups?

The general opinion amongst independent academic research is that they are helpful, though views on how helpful they are vary. The major criticism is that any efforts cannot work in a vacuum within society; so long as the wider world remains at loggerheads, lasting impact will not be achieved.

This smacks of defeatism. Children of any cultural, socio-economic or political background can be educated in the same building, learning and playing together. They typically grow into more tolerant and accepting adults. The proof is not just in the four schools currently in Israel, but in examples of successful integrated schooling worldwide. In Northern Ireland, a thriving and expanding integrated school system, educating Protestants and Catholics in the same buildings, has played a key role in healing divisions and sectarian strife. The first integrated school in N. Ireland — Lagan College — opened in 1989 with just 28 pupils and today, schools throughout the country are educating close to 18,000 pupils.

However, despite the opportunity they present, bi-national and bilingual schools in Israel are not proving as popular as one might expect. Since Israel opened its first integrated school in 1984 — five years before N. Ireland —-little progress has been made in increasing the number of schools or enrolments.

This limited progress stems internally from 1) a lack of institutional support and 2) mutual suspicion from the Arab and Jewish community that integrated schooling somehow diminishes their cultural heritage. The international community contributes by continuing to focus on high-profile news of abductions, bombings and murder, to the neglect of education issues.

It is important that efforts are made by the Israeli government, the international community and local groups to increase enrolments at these schools. Whilst critics continue to doubt the extent of their benefits, there is no ignoring the experiences of students. To quote Itamar Koretsky, a nine-year-old student at an Israeli integrated school: “At first studying alongside Arabs takes some getting used to, when you grow up in a Jewish home, you’re taught certain things. But when I came to class and met everyone, I realized that there are good Jews and bad Jews, good Arabs and bad Arabs. Some Arabs are better than some Jews.” [1]

Unequivocal institutional support must be forthcoming from the Israeli government and its Ministry of Education. If schools are to become powerful centers for promoting reconciliation, the wider community needs to be fully supportive of its aims, a situation that is greatly aided by institutional support.

The international community, and the United States in particular, need to pressure Israel to reform their segregated and discriminatory school system in favor of a more cohesive system which values Arabs, Jews and other minorities as equals. The current, fundamental lack of equality between Arabs and Jews in Israel is a major stumbling block for the future of a bilingual, bi-national education system in the country. International pressure can help push the Israeli government to ensure greater equality and inter-community integration.

Parents probably have the most important role to play. Beyond the political pressure parental groups can have on government policy - as they did in N. Ireland - parents ultimately decide which school to send their children to. Action starts at home and parents themselves need to be made more aware of the benefits of integrated schools as a route to a more peaceful environment than they have had.

The integrated education system in Israel should be a key pillar in the building of a peaceful State. Political buy-in, international endorsement and grass roots support are all needed if this opportunity is not to be missed.

Ilona Drewry is a British teacher, living in New York City and currently completing an MA in International Education and Development at Columbia University. Ilona has lived, travelled and worked in the Middle East, including a volunteer placement for PMRS (The Union of Palestinian Medical Relief Committee), a grassroots, community-based Palestinian health organization in Ramallah.

Endnotes

[1] “Unique in a Divided Land, Israeli School Embraces Jews, Muslims, Christians”, M. Chabin, Religion News Service, 23 December 2004.

Related Links