The Electronic Intifada 10 February 2004

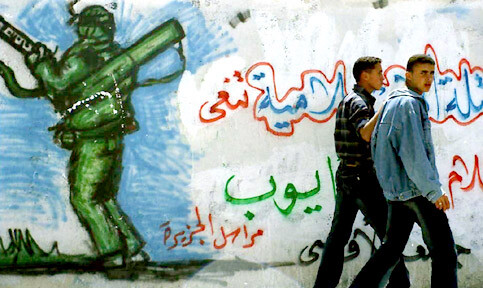

Writings on a wall in Gaza (Helga Tawil)

The International Crisis Group (ICG) has published in-depth reports about emerging problems and conflicts all around the world. They usually reflect solid research and thorough analysis and provide thoughtful recommendations. Thus, one would expect the ICG to offer an original and independent approach to the Arab-Israeli conflict. Unfortunately, however its contributions have often been little more than revisions of cliches and dubious projects already in circulation.

ICG’s latest report, “Dealing with Hamas” (26 January 2004), is no exception. One of its flaws is evident in its title - its authors seem to accept and endorse the widely-held view that had it not been for Hamas and suicide bombings, the region would be much closer to peace and security. This assumption has the attraction of being simple, and politically uncontroversial in the west, but it is also wrong.

Too often, we have seen that anyone who tries to explain Palestinian violence against Israeli occupation as being anything other than pure, evil, and aimless terror, is himself or herself accused of “supporting,” “encouraging” or “excusing” terrorism. A recent example of this was UK Member of Parliament Jenny Tonge, who was dismissed from a senior post in her party for merely saying she understood how the brutal conditions under which Palestinians are forced to live, could lead some individuals to seek revenge in the form of suicide bombing. The ICG apparently did not want to make Tonge’s “mistake” of trying to understand what is actually happening on the ground and how events are connected with each other.

Any meaningful analysis, whose purpose is to promote reconciliation and peace, should courageously and objectively present all the facts of any such conflict. Only this can produce a balanced and useful assessment. After all, the conflict between Zionists and Palestinians began in the 1890s, and yet the first suicide bombing did not occur in the 1990s. Surely there must be something more than evil, hatred and pure fanaticism at work? Being opposed to Hamas’ methods does not free us from the responsibility of placing the organization and addressing it in a broader context if we are to have any hope of making progress.

If Hamas and “Palestinian terror” are problems and obstacles to peace, much more so is the occupation - which includes daily terror and violence by Israel directed at Palestinian civilians, for the purpose of taking their land away from them and giving it to Jewish religious fanatics.

Yet the main difference between Israelis and Palestinians is that the Israelis have warplanes, tanks, bulldozers and missiles. They can, from the unchallenged safety of the skies, or from great distance attack Palestinians at little risk to those doing the killing. The result is that Israel, with its sophisticated weapons, has killed - from any moment you choose to measure it - far more Palestinians than Hamas and its like have killed Israelis.

While Israel tries to portray, and many in the west see, suicide bombings as a sort of incomprehensible religious-ideological statement, many Palestinians view this tactic as the last and most effective weapons-delivery system they have. In effect, it is the strongest weapon they have to balance Israel’s terror. Yet when Israel strikes at the heart of Palestinian cities killing innocents, it can easily be portrayed in the international media as “self-defence,” while any Palestinian response, which produces identical results on an Israeli street is termed “terror.” This difference in perception and standards is the key to understanding why there is so much tolerance, if not outright support, for suicide bombings in the region.

Singling Hamas out as the main problem suits Israel because it diverts attention from the fact that it is occupation, dispossession and colonization that provide the fuel for the conflict and violence, and Israel’s refusal to change its ways despite all efforts for peace. Yes, it is easy to blame “both sides,” but the reality is that when there is no violence, Israel builds settlements, and when there is violence Israel builds settlements. And of course Israel cannot build settlements without itself using violence constantly, because the people whose land it is taking naturally do not move aside willingly. Israel builds settlements not because of the presence or absence of violence, but because its appetite for Palestinian land is and has always been insatiable. This is the basic problem that must be addressed. Everything else is a symptom.

The focus on Hamas equally suits the Americans because American leaders do not want to pay the high domestic political price of refusing to accommodate whatever Israel wants. And it also suits the Palestinian Authority, because as the ICG report correctly notes, the influence of Hamas is increasing because of the harsh military and economic punishments imposed by Israel, and it is now close to “dominating the Palestinian political scene.” Yet all of the world’s condemnation of Hamas, all of the assassinations, all of the freezing of bank accounts, all of this, has done nothing to weaken Hamas. Given that so many powers benefit from the focus on Hamas, it would be hoped that ICG would offer a more challenging analysis.

To be fair, the authors are quite astute, observing correctly that the strength of Hamas derives from varied sources, including “clear ideology, simple agenda, cultivation of a popular base, effective social welfare network, Islamic credentials and ability to hurt Israel.” Hamas has also, according to the report, benefited from Palestinian Authority “failures as a proto-state to protect its people’s well-being and as a political actor to protect its self-determination.” Hamas “appears to have wagered successfully” throughout the Oslo process on the PA’s inability to deliver. Hamas “[u]nlike most radical Palestinian groups, secular or Islamist,” the report states, “is sensitive to public opinion, skillful at reading popular moods and acting in ways that are basically congruent— or at least not inconsistent— with them.”

On the basis of this record, one would expect Hamas to make sweeping political gains in any democratic process. And there is no shortage of calls for Palestinian “reform” and “democratization,” especially from Israel and the US. Certainly, Hamas could expect to do as well as, or even eclipse the Palestinian Authority.

But if the authors can recognize that Hamas is a complex movement with many sources and bases of support, stemming directly from the conditions and experience of the Palestinian people under occupation, then why are their conclusions framed around the concept of “dealing with Hamas” as if it were nothing more than a small, alien gang disconnected from the environment which created it?

Granted, the report does in fact advise against “a strategy based on military action alone,” but only because it does not work, not because it is not right; “it is unlikely to meet the security and ideological challenge the Islamist movement presents,” the report says.

The alternative, “and the surest course” the report recommends, “would be to mobilize real pressure on Hamas to join the mainstream by closing down its military wing or risk becoming increasingly vulnerable and irrelevant.” But pressure by whom? And who should decide what the “mainstream” is other than the Palestinian people? And why should any Palestinian resistance group disarm before the occupation ends? It is one thing to call on Hamas to stop deliberately targeting civilians, but to tell them to disarm is to say they have no right to resist at all, not even against armed troops in their own towns and refugee camps.

The world is very good at telling the Palestinians what they may not do. But for decades the world has sat by wringing its hands while Israel has carried out a continued process of colonization and ethnic cleansing without any effective international intervention. Is it not then time to allow the Palestinians to decide for themselves how to choose their leaders, and decide on their policies to win the freedom for which the international community is not willing to lift a finger? It is time for outside powers to stop deciding which Palestinian factions or figures should be recognized or “empowered, ” and for Palestinians to be allowed to decide this through their own, not externally-imposed, democratic process.

Because the ICG report lacks originality and direction, it offers in some sections ideas which were rendered unimaginable in others. The way to “deal with Hamas,” the report suggests, is based on four elements: a ceasefire, disarming Hamas and transforming it into a non-violent political party within the Palestinian system, securing Israeli agreement to the ceasefire, and a “detailed vision of a comprehensive political settlement” provided by the so-called Quartet.

This is both simplistic and naive. Each of these elements depends on the success of the others. As we have seen repeatedly, such processes are bound to fail, especially when the steps offered are illusory. Let us look at the four elements in reverse. The Quartet has nothing to offer since its notorious Road Map, which failed instantly, except repeated calls to return to the Road Map, which everyone knows is dead. In any case, the roles of the UN, the EU and Russia, three of the members of the Quartet, have been reduced to those of mere observers since they have surrendered all their authority in the matter to Washington, and relinquished any space to act independently. With Washington in full control, and in no mood to initiate any action that may annoy Israel in an election year (or apparently in any other year), one can only expect stalemate, and of course continued deterioration and violence. This means there will be no ceasefire, no disarming of Hamas and no renunciation of violence from any side. What this underscores is that violence is not something that stands in the way of a serious political process. Rather, violence is the result of the absence of a serious political process.

In contrast to its prescriptive approach to Hamas and the Palestinians, the ICG takes a much more cautious approach to Israel, which is left with ample leeway to sabotage the whole scheme without officially violating its commitments.

As part of the proposed scheme, Israel would “agree to cease the policy of armoured incursions, collective punishment, such as home demolitions and generalized arrests, sweeps and targeted killings except to prevent imminent deadly attack.” But Israel claims that every one of its actions in the occupied territories - whether an assassination of a Hamas official, or killing an unarmed activist of the International Solidarity Movement — is to “prevent an attack.” Since Israel’s claims are unverifiable, in reality this exception means that Israel is not restrained at all. While Israel had to work hard in the past to convince outsiders that it should have the exclusive privilege of violating ceasefires, this time ICG grants it willingly. And why the biased assumption that it is the Palestinians who will violate the ceasefire (hence the Israeli right to “prevent” attacks)? The reality time and again is that Israel is the party that has violated both official and unofficial ceasefires, restarting episodes of horrible bloodshed.

Even where Israel is asked to “revoke… economic and other punitive measures against the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip…” it is allowed to observe that commitment only if it is “consistent with its legitimate security needs.” Of course Israel alone gets to decide what its “legitimate security needs” are, and in practice there is not an atrocity it has committed that it has not justified in these terms.

A final point, which reflects the total lack of seriousness of this report is the recommendation that Israel “restrict the West Bank separation barrier to the 1967 line, freeze settlement activity and remove settlement outposts.” Does this mean Israel is being asked to actually relocate the wall it has already built? And by asking only that the settlement “outposts” be removed, is the ICG implying that those built before March 2001 should stay where they are?

Such forthrightness when it comes to the Palestinians, and vagueness and hedging where Israel is concerned is typical throughout this report. The overall result is that a document that contains a lot of interesting facts is too unbalanced to be taken seriously as contribution to moving forward.

Ambassador Hasan Abu Nimah is former permanent representative of Jordan at the United Nations.