The Electronic Intifada 20 August 2025

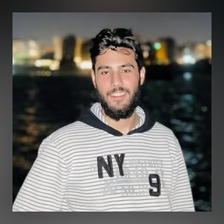

Mohammed Hamo at the library at the Islamic University of Gaza in August 2023, three months before his martyrdom.

I can’t remember how many times my friend Mohammed Hamo and I fought.

We would argue over the silliest things – where we would hang out, when we would hang out next or who would pay for the taxi this time.

Mohammed and I would even fight over who would play as the Barcelona team in a football video game.

But no matter how many times we would fight, we would always reconcile quickly.

In October 2023, days before the genocide began, Mohammed and I fought when I went out to attend my other friend Osama’s graduation party.

Mohammed didn’t speak with me for days after. But it was Mohammed who called me first on 7 October, asking how I was doing and where I was.

I reassured him and asked about his situation, and he told me that he and his family were fine, though they couldn’t sleep at night because of the bombardments.

That was our last fight together.

Knowing Hamo

If Mohammed was known among his friends for one thing above all else, it would be his laugh.

He had a laugh that radiated pure joy and childlike innocence. It would burst out of him with a high, ringing pitch – drawn out just a little longer than expected – before breaking into staccato bursts.

His wide grin would stretch across his face as he laughed, making anyone who happened to be there – most likely our friends Khaled El-Hissy and Mahmoud Alyazji – join in laughing, unable to resist.

He would laugh at the silliest things.

And that’s what prompted my first interaction with Mohammed – he laughed at my family name on the first day on campus.

It was in 2020. I had just attended one of my first lectures at the Islamic University of Gaza, and I sat in a shaded area to rest a bit.

Mohammed walked over and sat beside me.

I wasn’t very sociable then, so I stayed quiet.

He greeted me and asked how I was doing.

I did not know him, but I felt like I had to respond as I hadn’t found much to do on that first day. So I said I was doing OK.

“What’s your name?” he asked next.

I replied, a bit grumpily, “Khaled Al-Qershali.”

Mohammed chuckled at my family name – Qershali comes from the Arabic word qershala, Palestinian biscuits enjoyed with warm milk or tea.

It was something rude to do, but Mohammed’s laugh was contagious. I laughed with him.

Our conversation carried on as we talked about our tawjihi results, and soon after, Mohammed and I went to eat falafel together.

From then on, we hung out after class until we eventually became best friends.

We studied together, played computer games, tried new restaurants and spent nights at each other’s houses – usually joined by our two other close friends, Khaled and Mahmoud.

Mohammed and I also took extra courses outside the university during the summer.

After the courses, we would go to any cafe on our way, open my laptop and play video games until dawn.

Birthday cake

Just as Mohammed would laugh at the silliest things, with the same childlike manner he would also get mad at other silly things.

On 29 July, Mohammed and I were planning to try a new Syrian shawarma restaurant called Chef Warif.

Mohammed called me that day to make sure I was getting ready to go to the restaurant.

But on the same day I decided to see my neighboring friends whom I hadn’t seen for more than a week.

“That’s how it is now?” Mohammed asked.

“They are free today,” I responded. “I want to get together with them.”

He hung up, saying, “Fine. Do not talk to me or tell me you want to go out again.”

A typical Mohammed reply.

I laughed, thinking we would see each other tomorrow with no problem – just like before.

Mohammed celebrating his 21st birthday.

The next day on campus, Mohammed didn’t talk to me.

I tried teasing him — I sat on the same bench beside him in the lectures and went to the same restaurant he went to during the break.

He still didn’t utter a word with me. It seemed he was very annoyed.

I tried to make things right by inviting Mohammed to breakfast, but he refused.

I didn’t know what to do.

When I returned home, I remembered that Mohammed’s birthday was tomorrow on 30 July.

I went to my mother and pleaded with her to prepare a birthday cake today as I wanted to surprise Mohammed by appearing at his house and hopefully reconciling with him.

But my mother said that she wouldn’t be able to bake the cake today and she promised that she would prepare it tomorrow.

I begged her to make it by evening.

“I will try,” she said.

I went to take my usual long after-university nap and woke up in the evening.

When my mother told me that the cake would be made tomorrow, I was disappointed. I ate my lunch and sat to study.

But I couldn’t focus, thinking about how my surprise for Hamo failed.

At 11 pm, while I was still studying, my mother called me from the kitchen.

I went to check what she wanted.

My mother opened the fridge door, showing me the cake – already prepared.

I felt euphoric, though I realized it was a bit late.

I called our mutual friend Khaled to accompany me.

Khaled agreed and helped me prepare for the reconciliation as he went and bought three shawarma sandwiches.

When Khaled saw me, holding the cake in my hands at midnight, he laughed and told me that it was a crazy idea to be doing this at such a time.

We took a taxi and reached Mohammed’s home.

I hid behind the door while Khaled knocked.

But it seemed Mohammed was asleep.

We didn’t give up – Khaled kept calling until Mohammed finally woke up and came to open the door.

Still half-asleep, he giggled and asked Khaled: “What brings you to my house at such a late hour?”

“Happy birthday,” I said, stepping out from behind the door with the cake.

Mohammed grinned wide and laughed again: “And what brings you here? I thought you were still grouchy with me.”

“Are you going to let us in or not?” I asked.

“No, you go home,” he joked, pointing at me. “But Khaled, you can come in.”

Then, laughing, he waved us both inside.

Once we entered, Mohammed went straight to wake his mother, Um al-Abd, teasing her: “Yama, you were sleeping while my friends brought me a birthday cake.”

Both Mohammed’s parents, Um al-Abd and Abu al-Abd, came and greeted us.

They loved Khaled and me, treating us like family because we were always at Mohammed’s side – encouraging each other in our studies, taking training courses together to enhance our skills and find work.

We gathered in the living room, lit the candles and sang as Mohammed laughed with us.

He blew them out, cut the cake and we shared shawarma before enjoying the sweets.

Mohammed wanted us to stay the night, but with classes the next day, we promised to come next weekend instead.

Knowing it was late and taxis scarce, Mohammed insisted on calling a taxi for us – and wouldn’t let us pay.

After that, Mohammed and I fought plenty of times again – whether because I beat him at a football video game, refused to sleep over at his house or chose to study for a different exam than the subject he wanted.

Then, there was our last fight at the beginning of October 2023, just before the genocide began, when I attended my friend Osama’s graduation party.

We reconciled when Mohammed called me on 7 October.

Just dots

On 13 October, I evacuated from the Nasr neighborhood in Gaza City with my family to a school in Deir al-Balah.

Mohammed and his family remained in northern Gaza’s al-Sabra neighborhood.

While displaced, I tried to reach him many times by phone, though I couldn’t contact him on WhatsApp or Telegram because of the internet outage.

On 30 October, I finally spoke with him. I asked about his situation, and he replied, “Alhamdulillah, we are still alive.”

Then he asked how I was managing as a displaced person. I told him how life was unbearably difficult – the nights were cold, and we had no blankets to keep us warm.

Mohammed sighed and said, “If I came with my family, would there be space for us in the school?”

There was no space – every classroom was already crammed with displaced families. But I understood his worries and intention to relocate from the immense danger.

So I reassured him: “Yes, if you came, you would find a place. The earlier the better.”

He ended the call, saying, “I’ll tell my father and call you later.”

Only a week later, on 22 November, I managed to reconnect to the internet and found that, on 15 November, Mohammed had sent me several messages – just dots – trying to check whether I had internet access.

I wrote back, asking how he was and where they were staying.

Mohammed never replied.

On 24 November, our friend Khaled messaged me on WhatsApp with words I will never forget: “Mohammed Hamo is a martyr. May he rest in peace.”

I did not believe him. But then I searched for Mohammed’s name on social media and found that he, his family and about 200 others had been massacred by the Israeli occupation.

I cried bitterly that day.

Whenever I remember Mohammed and our memories, my eyes fill with tears.

Envious

But my tears for Mohammed have decreased recently.

I stopped worrying for him – not because my grief has lessened or because I feel any relief at his absence or because my love for him has faded – but I stopped worrying simply because I know, with certainty, that Mohammed is in a better place.

I even feel jealous of him, may he rest in peace, and I wish I was him.

Mohammed was not displaced several times or forced to cook over a woodfire, surviving on scant amounts of water and sleeping without a blanket.

He had not gone to the Netzarim or Rafah aid distribution points, where hundreds of starving people seeking food have been killed by the Israeli army.

He did not wait hours for a bag of flour at an aid site only to get nothing. He did not go to bed hungry for days, feeling himself starve to death.

He was not forced to drink salty or contaminated water.

He was not left to wander with nowhere to shelter.

I consider Mohammed to be the luckiest as he did not spend the last two years of his life in fear as bombs shook the ground beneath him.

He did not have to mourn and bury his loved ones one by one until none were left.

Mohammed himself was never buried – his body still lies beneath the rubble, with no grave I can visit, even if the war were to end.

But I visit him every day. He is always with me, alive in my mind.

And as long as we – his friends – remember him, Mohammed will live on.

Khaled Al-Qershali is an English graduate working as a journalist in Gaza.