IRIN 4 August 2006

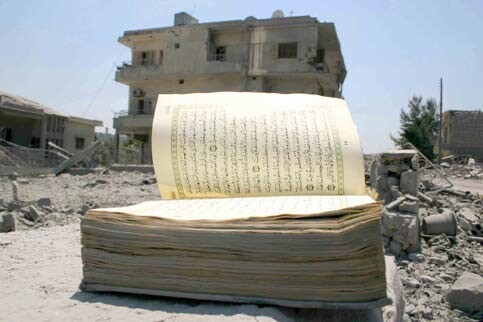

A Quran blows in the wind amid the wreckage of houses in Nabatiye, 2 August 2006. (Hugh Macleod/IRIN)

ARNOUN - The road inland from the port city of Tyre, 60km south of Beirut, is riddled with craters filled with mangled cars. A cattle pen is jammed with dead and dying cows left to starve after their terrified owner fled.

The road then forks east into the Aamel Mountains where entire towns are deserted, shops boarded up, bridges collapsed, and broken power lines flail in the wind.

The once-bustling market town of Nabatiyeh, 30km east of Tyre, is a Hezbollah stronghold, with the faces of those killed fighting Israel emblazoned on flags. Now, just a few grocers and roaming cats are left.

These mountaintop communities of Nabatiyeh province have been decimated by the Israeli bombardment, which began on 12 July in response to Hezbollah’s capture of two Israeli soldiers.

“Every rocket that lands here is like a sugar-coated almond to us,” said 74-year-old grocer Hani Hamadi, referring to the strengthening of the resistance. “As long as we have the resistance, the Israelis will not be able to take one inch of our land,” he said, sitting beside untouched piles of fruit and vegetables in the central square of Nabatiyeh, with the Hezbollah-affiliated Al Nour radio station blaring out military marching music.

Though Hamadi said his customers had dropped from thousands to hundreds - most of whom had taken advantage of the relative safety of a two-day ceasefire this week to do their shopping - the old man remained confident that Hezbollah would prevail in this conflict.

But across town, sheltering in the basement of one of the few houses left undamaged, an elderly caretaker, Sheikh Muslim, said it was time for both sides to end the conflict.

“I hope both sides can agree on a deal to end the fighting,” said the elderly man, from Syria’s northern city of Aleppo, who has lived in Nabatiyeh for two decades. “Every day is a day full of danger now. The aircraft are the most difficult to deal with. If it is just [artillery] shelling, then I can sleep, but not when the planes are dropping bombs.”

The caretaker said the last of the Lebanese families, who had been sheltering in the nextdoor basement, had fled Nabatiyeh after hearing of the deaths of civilians sheltering in a similar way in Qana. His only company were cats and canaries, two of which had died recently, he said, from the shock of Israeli air strikes.

His support for Hezbollah, however, remained unwavering. “Of course I support them. Does it require two people to sit down and discuss it?” he asked rhetorically, using a familiar Arabic expression. “As long as the people inside the country are united, nobody can come in.”

Lebanese Prime Minister Fouad Siniora has said that so far in this conflict 900 people in Lebanon have been killed and 3,000 been wounded, with the majority civilians and a third of casualties children younger than 12. Sixty-eight Israelis have been killed, including 27 civilians, according to the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).

On the frontline

Arnoun is another mountaintop village in south Lebanon, just 5km from Israel’s border. Munir Tawbe’s family is the last one remaining in the upper part of Arnoun. Of the estimated 1,500 people who used to live there, only three households remain.

The village has been in the frontline of the conflict since the Israeli military launched its largest ground offensive into Lebanon since 1982. Israel withdrew from south Lebanon in 2000, but the Lebanese government and Hezbollah have insisted since that Israel must also leave what they claim is the Lebanese territory of the Shebaa farms, on the borders between Lebanon, Israel and Syria, which Israel has occupied since 1967.

“This time there will be no occupation, we will die before that happens,” Tawbe said.

The family’s house is set against the dramatic ruins of Beaufort Castle, the mountain fortress just above Arnoun that has been a strategic stronghold since the Crusades.

Tawbe, his mother, three sisters and younger brother listen all day to the near-constant sounds of Israeli artillery pounding suspected Hezbollah positions in the valley below. “We cannot leave because we cannot rent a house and we do not have family elsewhere, so we have been living in the basement,” explained the young man, whose father died when he was a child.

The family is living off fried potatoes and food contributed by the few Lebanese soldiers remaining to man a checkpoint on the road leading up to the village.

“When the shelling is going on we just sit in the basement and think about our lives,” Tawbe said, looking over the scorched earth less than 10 metres from his house. “Or I try to analyse the sounds of the shells to work out where they are going to land.”

Related Links

This item comes to you via IRIN, a UN humanitarian news and information service, but may not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its agencies. All IRIN material may be reposted or reprinted free-of-charge; refer to the copyright page for conditions of use. IRIN is a project of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.