The Electronic Intifada 3 April 2025

An early morning walk through Gaza City reveals a surreal, eerie landscape.

APA imagesOne early morning in November, with the darkness just before sunrise enveloping me, I left the Beach refugee camp in Gaza City and made my way to Al-Ahli Arab Hospital.

My father was receiving post-surgery treatment there after his diabetic foot condition worsened and he had one of his legs amputated.

His spirit was shattered and three siblings and I took turns checking in on him. One brother is stranded in southern Gaza, relying only on fragments of news from occasional phone calls to learn of our father’s condition and our almost unbearable reality in the north.

I carried the weight of darkness in my heart and felt deeply anxious moving about at this hour. The short distance – maybe 7 kilometers – to the hospital felt endless. An Israeli drone hovered above, seemingly tracking my every step. My heart pounded as I feared the sudden strike of a missile. The streets were eerily vacant.

I paused at a corner, staring at soil still stained with the blood of my son Rauf’s friends who had been playing marbles in this spot just a few weeks earlier when an Israeli drone pilot had fired a missile at them.

Their five young bodies were torn to pieces, their innocent game ended in violent death.

Rauf had left the game earlier when his grandmother called him in for lunch. He was fortunate, but he still weeps for his friends, who had been displaced from different corners of Gaza to the camp – united by tragedy, bound together in blood.

A little further ahead, I paused again, this time to remember five of my friends.

Like the fingers of a hand, they were inseparable. They were volunteers, dedicating themselves to aiding the wounded during an Israeli raid on the Beach camp in June.

They sat beneath a lone tree, laughing – until their laughter was shattered like shards of glass, their bodies sent skyward by a merciless missile. I saw them perish that day as if they had never existed.

With cemeteries full, they were buried side by side in the camp’s park, aligned like jasmine blossoms in the direction of prayer, the qibla.

A cruel irony

The road is not safe.

Every house along the Tariq Ibn Ziyad street has been destroyed, its edges blurred by rubble and dust.

There was no echo of the Lebanese singer Fairuz’s songs in the narrow alleyways as there always used to be in the mornings. Only my own hesitant footsteps disrupted the silence.

The drone above kept watching me.

Daylight broke. People whose homes had been destroyed, stirred in the storefronts where some had built makeshift shelters, seeking safety in the skeletal remains of bombed-out buildings.

I mumbled to myself as I passed a house with a band of horses tethered outside, maybe a family of laborers transporting goods by horse-drawn carts. They had taken refuge in a home that once belonged to a wealthy family, perhaps owners of luxury cars and SUVs, who fled southward.

And so, I thought, a displaced family, maybe one that long struggled with poverty, now dwells in the ruins of an opulent home. A cruel irony.

In Gaza, madness is the new normal.

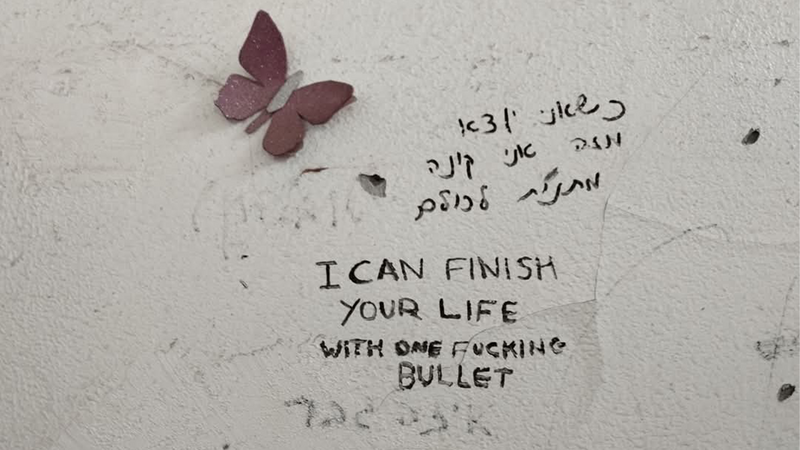

Graffiti near Al-Shifa Hospital.

At an intersection near the spot where Al Jazeera journalist Ismail al-Ghoul and cameraman Rami al-Rifi were killed in a July 2024 Israeli attack, a solitary sycamore tree stands.

It is almost the only thing still standing here. Homes have turned to dust, mosques and churches to ruins. The barricades, rubble and shattered pavements make movement here nearly impossible. A newly built villa, completed just two months before October 2023 at what must have been great cost, is now a heap of debris.

Closer to Al-Shifa Hospital, the terrain transforms into mountains of rubble. On a nearby wall, someone – likely an Israeli soldier – has scrawled threatening graffiti in English.

There is no life left in this city.

Further ahead, Dar al-Kalima University has been silenced. The Gaza branch of an art college set up to empower local artists and which offered art therapy classes to children traumatised in Israel’s repeated bombings over the years, was completely destroyed by the Israeli military a year ago – leaving behind only the somber remnants of an unspeakable genocide.

From the ashes

For a moment, I thought I was alone in this wasteland. But I was wrong.

As morning broke, I saw a few young men gathering firewood. One struggled to cut down a tree. A child scavenged through the wreckage, salvaging bits of furniture. I wondered whether the young men had been university students? Engineers?

Gaza’s schools have become shelters. Then, one by one, they became mass graves.

My journey to Al-Ahli Arab Hospital was long, my feet weary, my clothes dust-covered. As I passed the ruins of Al-Shifa, once the largest hospital in Gaza and perhaps all of Palestine, I saw only a surreal, haunting landscape.

To the west, martyrs have been planted like flowers. To the south, the morgue has become a landfill. To the east, remnants of massacres, where doctors and patients were exterminated, then buried in mass graves.

As I neared Al-Ahli, the streets swelled with those queuing at the only remaining bakery in the area. A large crowd of hundreds – women, children, the elderly – waited in line, jostling for a loaf of bread that would not last them half a day. It was a scene beyond comprehension, beyond words. It resembled a prison yard.

How did we reach this point? How do we end it?

I continued, past the charred remains of Rashad Al-Shawa Cultural Center, where once we held literary and artistic gatherings. Its ceiling now gapes open, pleading for salvation, its library emptied, not by scholars, but by the desperate, who will have used its books as fuel for cooking in the absence of gas.

Borges, Marquez, Naguib Mahfouz, Al-Bayati — all turned to ash alongside Einstein and Ibn Khaldoun, Marx and Ibn Kathir.

In the heart of Gaza City, the Phoenix Monument still stands, a testament to an ancient Canaanite legend which has the mythical bird die in fire and be reborn from the ashes.

It is a message to the world: Gaza will rise again, just as it always has. The city has been a graveyard for invaders for millennia, and it will remain a thorn in the side of occupiers.

Despite the carnage, despite the blood, we know that the road home is paved with suffering. But what matters is the destination.

Yousri Alghoul is an award-winning novelist, short story writer and essayist in Gaza.