The Electronic Intifada 13 August 2008

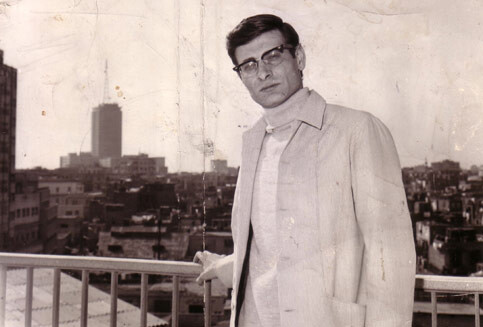

A young Mahmoud Darwish in Cairo. (Al Akhbar)

At a time when many feel that the Palestinian cause is dying, the death of the poet Mahmoud Darwish following open-heart surgery acquires added poignancy.

Variously described as “the Palestinian national poet” or “the Arab poet laureate, Darwish was 67, exactly the same age as his friend Edward Said when he died five years ago. Both men were seen as embodying the aspirations of their people, both served on the Palestinian National Council, and both resigned in protest against the Oslo Accords which, as they rightly anticipated, sold out Palestinian rights for no tangible result.

While Said philosophically endured the status of icon and saw it as helpful in his task of representing Palestinian claims, Darwish repeatedly but unsuccessfully rebelled against it and felt burdened by being forever associated with a poem such as “Identity Card,” from his first collection:

Write it down!

I am an Arab

I have a name without a title

Patient in a country

Where people are enraged

He protested the view that “Palestinians are supposed to be dedicated to one subject — liberating Palestine. This is a prison. We’re human, we love, we fear death, we enjoy the first flowers of spring. So to express this is resistance against having our subject dictated to us. If I write love poems, I resist the conditions that don’t allow me to write love poems.” Nonetheless, he also asserted that “most of my poetry is about love for my country.”

The violent creation of the state of Israel in 1948 saw the village of Darwish’s birth — Birweh or al-Birwah — wiped from the map. After a brief exile in Lebanon, he returned illicitly to Galilee and settled in Deir al-Assad, becoming an activist in the Israeli Communist Party. Subsequently he moved to Moscow, Cairo, and Beirut where he witnessed the Israeli onslaught in 1982. He recorded his impressions in the powerful prose memoir Memory for Forgetfulness, where normal everyday life is symbolized by the humble cup of coffee. Darwish’s addiction to this beverage may have aggravated his later heart ailment, necessitating major surgery in 1984 and again in 1998 during which, in the latter case, he was briefly clinically dead.

It was in Paris — over coffee! — that I met him in the spring of 2003, an encounter arranged by his old friend the historian Elias Sanbar (now Palestinian ambassador to UNESCO). I secured his autograph on my copy of the French edition of his selected poems, as translated by Sanbar, and invited him to visit Ireland at his earliest convenience as a guest of the Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign. He expressed his enthusiasm for the idea, and wondered whether he would be able to meet Seamus Heaney. He asked me about the Irish language, and seemed genuinely shocked when I told him that only around one percent of Irish people spoke it as their first language. “You cannot have a national identity without a living language,” he exclaimed. He was a little nonplussed by my lack of enthusiasm for the Celtic tiger, and I got the impression that his view of Ireland was colored by Edward Said, who saw the country through rose-tinted post-colonial glasses.

Curiously, he was obsessed with the notion that US President George W. Bush was back on the bottle. He had just seen him on the TV news emerging from an airplane, and was convinced that he looked drunk. I suggested that the US president had never really sobered up in the first place.

Somehow, sadly, the proposed visit to Ireland never took place. I telephoned him about it on several subsequent occasions, but there was always something in the way. The last time I rang him at his home in Amman, Jordan (he also had a residence in Ramallah in the West Bank), was in the immediate wake of Hamas’ surprise victory in the 2006 elections. He was distraught and aggrieved, and under the circumstances I felt that it would be inappropriate to press him. How I wish now that I had been less delicate!

Like Garcia Lorca, Mahmoud Darwish was a cosmopolitan modernist poet whose work nonetheless embraced a lyric dimension that enabled it to be set to music by many composers and sung by such popular artistes as Marcel Khalife, Fairouz, and Reem Kelani. His longer poems included the complex “Mural” (2000), a reflection on his survival after surgery, and the more direct “State of Siege” (2002), inspired by Ariel Sharon’s barbarous reinvasion of West Bank cities, and again instancing his beloved poison as a symbol of normality:

Our cups of coffee. Birds, green trees …

The water in the clouds has the unlimited shape of what is left to us

Of the sky. And other things of suspended memories

Reveal that this morning is powerful and splendid,

And that we are the guests of eternity.

Mahmoud Darwish left no children to whom we can address our condolences. Instead, it is the Palestinian people as a whole who must receive our commiseration for the loss of their most vibrant voice at a time when so much else is being lost to them.

Raymond Deane is an Irish composer, author and activist.