West Bank 4 November 2004

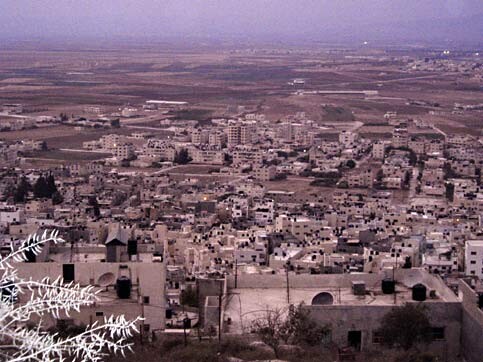

Arrabeh, a view of my fathers village where I stayed.

The thing that always surprises me about the West Bank is how it never seems to change significantly. Understandably, there is a lack of progress. But I still find it disheartening in a sense to return to my parents homeland and find that, besides a building or two or a new shop, everything is the same as it was four, eight, or even twelve years ago.

My last trip to the West Bank was in 2000, just a week before the Intifada broke out. West Bank remains in essence as it was then, however, there are more road closures and greater difficulty entering. Even leaving is a daunting prospect considering the number of checkpoints (no less than five on the route I took to Allenby Bridge) and a 4.30am departure time.

My experience in West Bank was extremely memorable, despite an appalling beginning. I spent one week in my father’s village of Arrabeh (about 12km from Jenin), and visited family in other nearby areas, including Jenin.

I left Amman at about 8.30am and by 11.00am I was on the bus to get to the West Bank side of Allenby Bridge. The buses are meant to come every half an hour however I had waited for over an hour.

On the bus I sat next to an old Arab-American woman, a New Yorker, who makes regular visits to Palestine where she has family. She asked me how much I knew about the situation there and I told her that I was well-informed and looking forward to getting there. She brought up the Jenin massacre and said that she had gone there after to take pictures, but no one was allowed in. She had taken pictures, however, and I asked how she got them through when she left. “They don’t care about what you take out, they’re just happy that you’re leaving, because you’re rubbish to them,” she said without flinching.

The house next door to my aunts apartment in Arrabeh that was destroyed; note the shed next to it where the chickens were housed was also heavily damaged.

We eventually arrived at the bridge on a bus with all foreigners (including Arabs like myself who have foreign passports). At the checkpoint I noticed about five buses loaded with passengers and luggage on the roof, waiting to get through. At the bridge we had to wait until we were given permission to get off the bus. The Arabs who were waiting in line to get their luggage put through (passports and cases are given to someone who takes it to a soldier and stickers are placed on the luggage) were made to move away and sit on the grass. Apparently something suspicious had been found amongst the luggage so the area had been cleared. I later heard that the morning bus delay was due to another such suspicious object being found.

This particular day was a very hot one (even now the weather is extremely hot when it should be much cooler!), so we were quite surprised that they were made to sit out in the sun. One woman was holding a baby who seemed to be screaming (we couldn’t hear anything obviously but everyone’s attention was on the events unfolding), so a gentleman went up to her and took the baby to a shady area and started talking with the people there. A soldier quickly came up to him and said something and he moved back to where he was. If you could hear the gasps in the bus! We were shocked. The soldier had been carrying a cup of water and it had been assumed that she was going to offer it to the man for the baby. As it turned out, it was for her; they were in fact passing out cups of water for all the soldiers standing watch.

Jenin from above, after dark; very peaceful.

One of the soldiers had told the bus driver to move further away and eventually when the suspicious object had been cleared (after at least 10-15 minutes) he was allowed to move the bus back. We still had to wait, and eventually one of the passengers came to the front to ask what the further delay was. The bus driver spoke no English and asked him to sit down or else we would be made to wait longer (which someone at the front translated into English to him). The bus driver didn’t seem to be making this up as he looked extremely anxious, particularly as the man lingered. Eventually a few passengers at the front began to tell him in English to obey the driver and sit down.

Finally, we descended from the bus and collected our luggage. At the bus stop in the Amman section I had befriended an Arab-American woman who had with her her two children. She told me to stick with her at this point because I think she realised that I seemed a bit lost. The last that I had come through the bridge it had been a totally different process, but then again every trip into Palestine (and I have made a few) has always been a different experience. It was slightly chaotic as everyone seemed anxious to get inside. I eventually got my luggage through and when my passport was returned I went inside with my new friend and her children.

We waited in line to go through the security detector, taking off any jewellery and watches beforehand. I noticed a few of the Arab-American passengers I was travelling on the bus with sitting outside the inspection rooms, obviously waiting to go in. When it was my turn, I placed my handbag on the conveyer belt for it to be X-rayed and walked through the detector (exactly like the ones at an airport). It beeped and I was told to return and remove my shoes. This surprised me since they were very slim sandals. Nevertheless, I did as they said feeling slightly embarrassed that I had to walk barefoot through this machine. It didn’t beep this time so happily I continued on to get my visa.

There is a standard visa application form that must be filled out. I am not sure if the one I filled out is only for foreigners, but it was in English and said, quite ironically in my opinion, “Welcome to Israel”. Following my experience at the bridge, I felt that a more realistic greeting would be “Welcome to Israel; what do you want?”

When I submitted the visa application and passport, the lady serving me took her time. She hesitated a lot and loaded me with questions about where I lived, how long I planned to stay, why I came and so on. The booth had two women at the counters, but the lady serving me was discussing me with a third soldier who was present. The lady said “I’ll give you two weeks”, although she didn’t really say it to me, and even when she said it she seemed hesitant. My new friend had already gone through with her children but before she had, she had asked me what I was going to say as to my address there.

The main shopping area in Jenin.

I told her that I would say West Bank since that was where I was going. “If I were you I wouldn’t say that. Say Al-Quds (Jerusalem) otherwise they’ll give you a hard time.” I refused to do this however, as I didn’t feel the need to begin a lie that would never end. Finally I was handed back my passport, being given only two weeks stay (I was only going for a week so this was fine, but I didn’t feel it was necessary for them to change the visa from 3 months to 2 weeks!).

The next part is something that in many ways I would like to forget. I had not known what to expect of my travels into Palestine; family in Amman were mixed in their views, some urging me to go saying everything would be fine, others saying that the situation was too dangerous and that I should hold off (note that a very sophisticated communication network exists in Jordan and Palestine as to the status of the situation!).

After your visa is approved you must hand your passport to a lady (I’m not sure if she was security, a soldier or police) who checks it and lets you through to get your luggage. She was an extremely rude and aggressive woman who wouldn’t even hand me back my passport, instead slapping it on the table and telling me in her broken Arabic to go. I asked her to speak in English. I understood her, of course, but I wanted to make a point. She was just as rude in English. I walked into a fairly small area that included a roped-off section. In this roped-off section there was a room where the bags are checked.

I submitted my passport once again at another desk; the soldier took it, did something with it then slapped it onto a pile and ordered me (they don’t ask) in Arabic to go and sit down. I asked her to speak English and she said “Go take seat!” Now, I had no idea what the process was, especially as my new friend had already collected her luggage and left. However, the soldier wasn’t about to enlighten me.

Jenin’s main shopping area with many signs of life.

“My passport?” I asked, to which she said very loudly, “Go take seat!”. In a small act of defiance (which really hurt me more than them), I refused to sit, instead standing with my arms crossed for most of the time. I felt jittery in any case, so sitting would not help. An hour later a French lady who had been on my bus came through and we started talking. She was going to Jerusalem, and we made small talk as I speak a bit of French, but her English was good. She asked me how long I had been waiting and looked a bit concerned. The area was fairly small and there were just too many people for such a small area. There certainly weren’t enough seats were everyone to sit down.

This is the process. A soldier or someone else (an Arab) comes into the roped-off area with a few or several passports. The names are read out and if it is your passport you have to go into the roped-off area. They didn’t use microphones and didn’t speak very loudly over the din, so it was extremely hard to hear the names being read out. Many people stood at the rope in order to hear better, and the lady who had been extremely rude when I first entered this area kept getting up from her desk and extremely loudly would order everyone to move back. Irja la wara! Irja la wara! (“Go back! Go back!”) she yelled, with, and I do not exaggerate, a huge scowl on her face. The disgust is extremely obvious. On my last trip through the bridge, there had been no Intifada, but there was an insincere politeness from the soldiers (although perhaps some were sincere, I couldn’t know). There is no such pretence now.

I waited no less than two hours. I was ready to cry or scream or both. A poor old man in a wheelchair had been yelling to no one in particular, “What’s going on? What’s taking so long?” No one understood what was going on, how some people were getting through quicker while others were forced to wait. The French woman had earlier taken a seat and her name had been called within half an hour of her entry. When my name was finally called I was joined by three other travellers, all holding Middle Eastern country passports. We were taken to the side to a table where our hand luggage was scanned and even our passports were scanned by some device.

The soldier looked at the only other girl there and said, “Are you Amal?” She said no. He then looked at me and asked again, and I said yes. I would have assumed it would be quite obvious since I wear a headscarf and the other girl doesn’t. Another man in plain clothes came up to us and my passport was handed to him and he asked me if I was Amal. Once again I said yes. He walked away and the soldier said we could go. I had a feeling that he didn’t mean me, but as he hadn’t indicated otherwise, I moved to leave. He actually barked at me, “Not you!”.

I was surprised and not a little annoyed. I wanted to leave. I had been standing for two hours (minus five minutes at the end where I finally gave in and sat down just to be doing something different!) and I was tired. I had eaten only an apple earlier and I deeply regretted forgetting my bottle of water in Amman. The plain clothes man came back and told me to go with him. He led me into the bag-checking room and told me to take a seat. He wasn’t rude but he wasn’t friendly or polite either. He stood over me and was joined by a woman who, as I remember, was a soldier.

He began speaking to me, then suddenly stopped and said, “I’m Israeli security, by the way.” I honestly can say that I felt no fear, just surprise. You can’t assume that you will be trusted because you carry a foreign passport, but to be taken aside for further questioning? This was new to me. They began to ask me lots of questions such as the usual “Where do you live? Where do your parents live? Why did you come? Where will you be staying and with whom? Are you going anywhere else?” Then came the more interesting line of questioning:

“Do you work?” Yes.

“What is your occupation in Sydney?” I told them.

“Are you married?” Nope.

Back to my work. “Do you have a business card?” No, but here’s a driver’s licence.

I have no idea why I offered this to them, but I guess I was hoping to speed things along. The soldier noticed a photograph in my wallet.

“Who’s that?” she asked quickly, pointing.

“My nephew,” I replied.

“When are you leaving?” I told them once again what my intended period of stay was, emphasising that I had a return ticket to Sydney. They asked to see it, so I showed them.

“Did you pay for this ticket yourself?” Yes.

“Did anyone give you anything to bring in with you? What did you bring with you? How many aunts do you have? Do you have any other passports? Are you staying in Amman for the rest of your stay? Who were you staying with before coming here?”

They actually seemed to not know what to ask me at certain points, hesitating and looking at each other, then finally the man said, “Okay, you can leave now.” With relief I left, immediately thinking of my poor aunt who must have been panicking about me by now since it was so late. The soldier took me out and actually apologised, but I think she was referring to their broken English as she said something like, “I’m trying to practice” and she was all smiles.

I took my passport, grabbed my one piece of luggage and found the bus to the istiraha (the bus stop where you meet your relatives or find transportation to your destination). A man helped me with my luggage and saw me on to the bus. I couldn’t believe what I had just seen. The treatment, as though the travellers are animals, not human beings. While I expect their level of security, I guess I had always hoped for some basic respect. No such luck, as pointed out to me by someone, they don’t want you to be comfortable. The fewer coming in, the better.

Even on the way to the istiraha there is another checkpoint, run by Arabs who take the passports and check them inside an office. By this point I wanted to say “please just take it and keep it!!!” Luckily, my aunt was waiting for me at this checkpoint and with much relief on both sides we greeted each other. We took a taxi to another checkpoint where we would take another taxi (a “servis” which carries several passengers all going in the same direction).

The nicest bread I have ever tasted, homemade in an oven.

We walked behind a barbed wire fence to two soldiers standing at a counter. One of the soldiers took my passport (I was getting good at this) and inspected it. My aunt provided her hawiya (ID card, although some Palestinians do have Palestinian Authority passports that are not compulsory). The other soldier asked her something in Hebrew and she replied in Arabic that she didn’t know Hebrew. I probably rolled my eyes at this point, as I was pretty fed up and just said, “English! Do you speak English?” So he spoke in English and I translated into Arabic for my aunt. They asked where she came from, how she got there and why, as well as a few other questions. The other soldier turned to me and asked for my passport. I took it out again and told him that it had already been checked. Eventually the soldier who had checked it turned to him and said, “No, she’s okay”. So we finally made it to the servees (shared taxi) and were on our way.

I have many thoughts on what I experienced at the bridge, but my immediate response was that I had been profiled. A single, young, Arab-Muslim woman living in a foreign country - was I a security threat? The line of questioning certainly seemed to indicate the desire to establish that I had a life back in Australia, a life that I valued and intended to return to, and that I had not come courtesy of someone else or on a mission of some sort. My aunt initially suggested that Israel was always worried about foreigners coming in because they felt a responsibility towards them should anything happen and they are involved.

I disagreed totally with this, telling her what I was questioned about and she agreed that she was probably wrong, but that I had nothing to worry about as a foreigner. Of course, having a foreign passport makes little difference if there is gunfire, since a bullet is indiscriminate. The other take on their questioning is that lots of foreigners are coming in to join peace organisations; these people go to hot spots and stand in front of the tanks (like Rachel Corrie). One of my cousins actually mentioned that he had met an English woman recently who was off to the Gaza Strip in the name of peace efforts.

Palestinians are more aware of foreigners now and while they know little is being done by governments to help them, they do appreciate that there are many outsiders who will stand up in their name, or who at least want to know more. Some of my cousins pointed out their school in Arrabeh and excitedly told me that they had met many foreigners who had come to visit them there. While I am a foreigner myself, I was able to connect to my family, to any of the Palestinians I met on a personal level, while still being a bit of a curiosity. They ultimately view me as one of them despite our differences. There we were, both sides amused by (at times) broken attempts at a different language, the exploration of cultural variations, a happiness erupting that they have not been forgotten by the foreigner.

Related Links

Amal Awad is an editor in the publishing industry in Australia.