19 July 2024

Muhammad with his three sons.

Courtesy of the familyRafah city.

Jneineh neighborhood.

A three-story building.

Opening the door, the first thing Muhammad, my brother-in-law, sees are his children with their six pairs of brown eyes anticipating his arrival.

This routine occurrence was the highlight of the evenings for my nieces Misk, Mais and Sham and nephews Huthaifa, Ezzat and Obaida.

Muhammad, 36, always came back home after work, filling the U-shaped gathering of children with his serene smile to complete a circle with a hug.

The loveliest Friday feasts I had were when my parents, younger siblings and I would gather, forming another circle, at my sister Nour’s home in Rafah.

Muhammad would usually go to bed early, leaving his home a cozy private space for sisters’ chatter. Nour would start telling stories nonstop till dawn broke. I would listen lovingly.

I treasured those moments, always a blessed relief after long weeks of hard work, studying, teaching or finishing freelance projects.

On 11 November 2023 at 10 pm, an Israeli airstrike targeted and killed Muhammad, robbing Nour, Misk, Mais, Sham, Huthaifa, Ezzat and Obaida of their joyful evenings.

For months, my sister Nour stayed home, staring at the sky in silence.

But, as May 2024 approached, the family was forced to leave their home to flee Israel’s Rafah ground invasion.

“Will our home in Rafah stand?” Nour asked, fearing her children would be homeless as well as fatherless.

A broken circle

June 2024.

A tent in a camp for the forcibly displaced.

Visiting Nour no longer comes after a hard week at work or study.

Neither exists in Gaza anymore.

In fact, I don’t have to go far. Just out of my parents’ tent and turn left and there I find my sister Nour with her six kids inside their tent.

No stories.

No circles.

When the six pairs of brown eyes finally close in sleep, I bring two coffees.

Nour broke her silence. Stories followed, describing how she felt when Muhammad’s life was taken away from her and her children.

Unusually, under the current genocide, the family got a chance to say goodbye to Muhammad, whose body was brought back home for burial.

“Despite the unbearable pain in my heart, I have to feel grateful that Muhammad was given a proper burial, a luxury today,” Nour said.

But like her children, the loss of their evening routine has struck her hard.

“The image of him opening the door at the end of the day and coming home never leaves me,” she said, opening up after months of silence.

She is painfully aware that her grief is neither unique nor unusual in Gaza.

“I see helplessness in the eyes of all visitors,” she said. “No matter how much they love and support, they have their own pain.”

The genocide has torn our family apart. My parents miss their partially destroyed home. My brother thinks of his home, burnt to the ground. One sister is besieged in northern Gaza, fighting both famine and fear.

Nour’s fears for her own home have also been borne out. In June, her home was damaged in a bombing.

“Relatives sent me photos of the rubble. Even the pillars are gone.”

It was not clear from the pictures, but Nour held out hope that just one room might still be habitable.

“Sometimes I just want to scream out loud that I don’t want to live in a tent. My children deserve better.”

She is struggling, she said, with everything.

“Sometimes I wonder why am I still alive. Knowing that even our home won’t be there. I am consoled by memories only.”

Above seven skies”

Nour described the excruciating pain of what it was like for her children to live without their father.

“My 14-year-old daughter Misk loved eating. Since Muhammad was killed, all her meals have been accompanied by tears,” Nour said. “She stops eating once she has the first spoonful of food.”

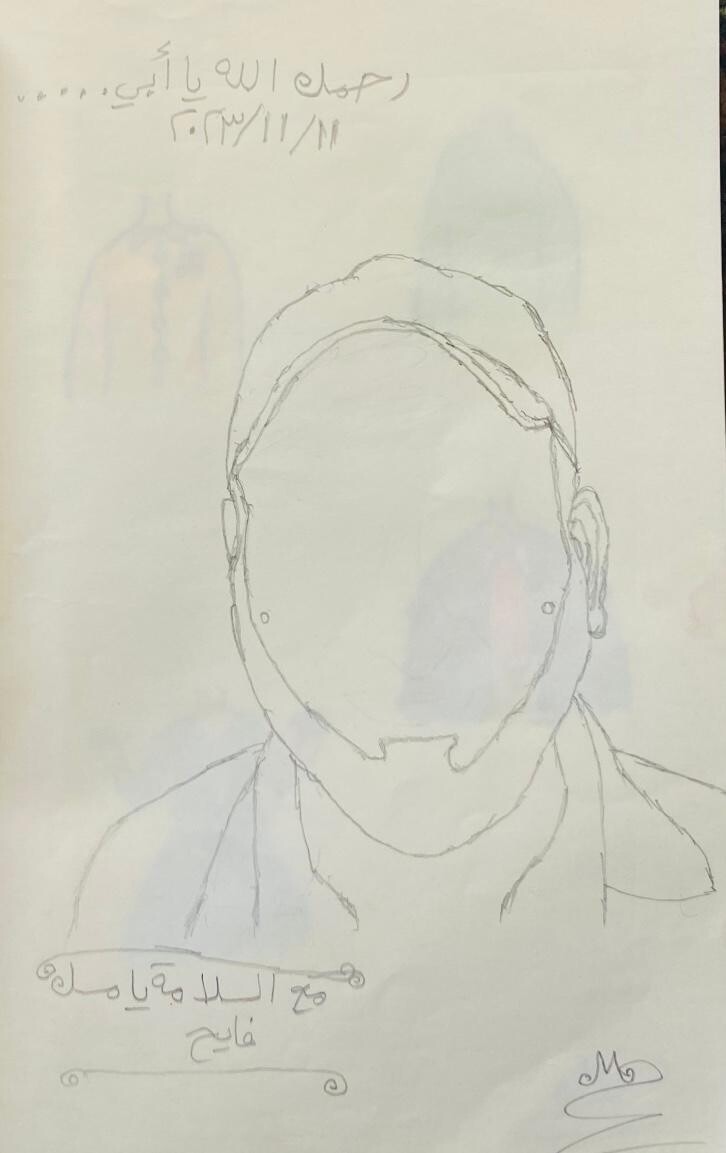

Mais’ drawing of her faceless father. “Rest in peace, baba,” the caption reads.

Courtesy of the familyMais, 12, used to draw cartoon characters with vivid facial expressions. But recently, Nour said, she had drawn a painting of her father without a face.

“When I asked her to complete the drawing,” Nour said, Mais “told me it was complete.”

Sham will turn 8 in October. Her dad had promised to make a photo album for her to celebrate the occasion when war was over, with their favorite moments together. Now that won’t happen, Nour lamented.

“My 2-year-old Obaida looks at the sky all the time,” she continued. “‘I love you dad,’ he cries, sending a kiss to heaven.”

“Obaida now has a full-time job of making me weep day and night, as he is always watching his dad’s videotaped memories,” Nour said.

One morning, she remembered, Obaida woke up smiling.

“When I asked him about the reason, he said happily: ‘I kissed baba.’”

When Huthaifa, 10, misses his father, he asks if there is “a Wi-Fi connection up above.”

“Ezzat, his twin, learns that his cousins traveled to reunite with their father. When he expressed how lucky they were to ride a plane above the clouds, Huthaifa rebuked him, boasting that his dad travels freely above seven skies,” Nour said.

Their grief, Nour conceded, had made it difficult for her to express her own.

“Listening to these daily conversations of my kids, I feel that expressing my own pain of losing a husband is just another hard task.”

Nevertheless, she has started remembering happier times.

“Muhammad’s very first words when I met him before we got engaged still resonate in my head. ‘May God help me give you a happy life,’ he said.”

Sitting in the tent that is now his family’s only shelter, she answered her late husband: “You did.”

“Our last days together were so sweet,” Nour recalled.

“I can’t forget how he didn’t eat unless he made sure that our circle was complete. ‘Where is Nour,’ he insisted when I wasn’t around in our last gathering.”

“Will our circle ever be complete again?”

Amna Shabana is a freelance writer, translator and trainer from Gaza City, currently displaced in the southern Gaza Strip.