The Electronic Intifada 17 June 2004

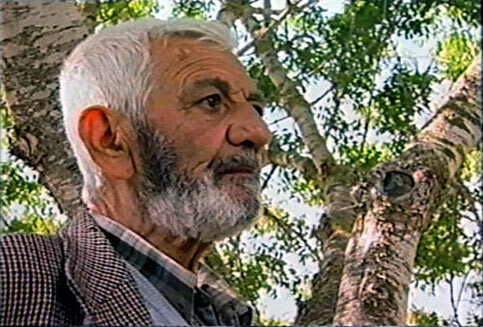

A Palestinian refugee surveys his family’s demolished village in “Keys”

“Mafateeh,” or “keys,” is a word that holds symbolic meaning for Palestinians, and refugees in Rafah, Amman, and Jenin alike can show you the keys to their houses that they temporarily fled or were expelled from during the time leading up to and during the 1948 war. And like Ali Nimer Harami does in the film Keys, these refugees can show you well-preserved pieces of paper that prove their legal claim over land that is currently inhabited by Jewish Israelis in what is now Israel.

In his beautifully shot and quietly powerful film, Salim Daw, whose family is also waiting to return to their original village, profiles aging Arab Israelis who were forced to resettle in other parts of the state after their villages were destroyed following their disposession. Explaining that his family fled their hometown of Birweh on 11 June 1948, because it was “raining bullets,” fellow Israeli-Palestinian Abed Alrameh Kaiyal says his family thought they would only be gone for two weeks. But 54 years later, he says, “I still have my key.”

As Kaiyal says this to the camera, a Jewish villager and a male relative approach the crew and reprimand them for not phoning and asking for permission from the landowners before filming. She says, “It’s been 40 years now that you’ve been shooting and telling stories,” she says, storming off. Kaiyal, who says that this happens every time he visits his family’s land, challenges her to show him her deeds to the land, but she doesn’t respond. This is how we coexist, he says.

Mohammed Ayed Arabat, who died shortly after the film was shot, recalls his childhood in Sajara during which Jews, Muslims, and Christians coexisted harmoniously, sometimes under the same roof. “Even the Jewish thieves and the Arab thieves were friends; they’d steal together,” he says. Now, he laments, “the entire landscape has changed.”

Israeli villas loom over the pastoral green of where the Arab villages once stood. Daw lets his cameras linger on the natural beauty of the land, and viewers enjoy close-ups of bees pollinating a flower, hear the rustling of the trees in the wind, and get a taste of the scenery so treasured by the refugees. Kaiyal is so invigorated by being on his family’s land that despite his old age and his disapproving wife, he begins to climb a raspberry tree, plucking off and eating its fruit.

Although their original towns have been razed over, and as Kaiyal watches Israeli-operated Caterpillar bulldozers raze his father’s grove of fruit trees, the refugees’ memories of home remain intact. Often telling stories as their grandchildren listen attentively, the mature Palestinians have clearly handed down their memories to the next generations. As is shown in the film The Children of Ibdaa, in which kids from the impoverished Jenin refugee camp in the West Bank visit the land on which their families previously lived, they feel a deep connection to their history and desire justice for their family’s past. And thanks to documentation such as Daw’s film, hopefully the desire for justice for the Palestinians who have been wrongly displaced from their land won’t be bartered for some paltry peace deal that will fail like so many have before.

One can only wish that Harami is correct when he says, “History has proven that a patient man who refuses to forget or relinquish that what is his, will eventually regain it.”

A recent graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Maureen Clare Murphy is Arts, Music, and Culture Editor of EI

Related links