Electronic Lebanon 30 September 2008

A toilet and kitchen area are contained within the 18-square-meter units and residents say water from the units above leaks through the ceilings, while sewage running under the floorboards is a sanitary hazard. (Hugh Macleod/IRIN)

NAHR AL-BARED (IRIN) - They look like cargo crates: long lines of prefabricated steel units, stacked two high, set on the edge of the ruined Nahr al-Bared Palestinian refugee camp in northern Lebanon.

Inside each airless 18 square meter unit there is a toilet, gas burner and tatty mattresses on the bare wooden floor. This is the bedroom, bathroom and kitchen for Palestinian families like Hayat Jundi’s, whose home in Nahr al-Bared was destroyed in last summer’s battle between the army and Islamist militants.

“All I do all day is fight with the neighbors above about the water that spills down into our room,” said Jundi, 55, as some of her four young children bustle around. “I’m irritable because I have backache from sleeping on the floor.”

Jundi’s husband, a bin man for the UN agency for Palestine refugees, UNRWA, has two other wives with children, so is only able to give her around $150 a month, she said. Food comes from UNRWA handouts and donations from the Lebanese Future Movement of parliamentary leader Saad Hariri.

Along the dark, dank corridor and up some steps, 19-year-old Marzouka Mohammed Khadr, a young Lebanese who married a Palestinian from Nahr al-Bared, shows us the room where she is raising her young family.

“We used to have a private kitchen and bathroom; now it’s all in the same room,” she said, pointing out the cockroaches scuttling into the cracks in the wooden floor beneath her makeshift sink. Flies buzz around as the breeze catches the smell of sewage seeping from the floor.

Food aid, rental subsidies under threat

Yet life for these 300 Palestinian families and their thousands of other kinsmen displaced from Nahr al-Bared — some for the third time in their lives — might very soon be getting a lot worse, in large part due to the neglect of the region’s Arab states.

UNRWA is warning that unless its flash appeal for $43 million for emergency humanitarian assistance is met soon the agency will be forced by the end of October to stop distributing food aid to 3,100 families and halt rental subsidies supporting 27,000 Palestinians displaced from Nahr al-Bared.

So far only the United States has come forward with emergency funds, donating $4.3 million for shelter, health and education, part of a total commitment this year of $23.5 million to UNRWA’s reconstruction of Nahr al-Bared.

In June, UNRWA said it needed about $445 million to rebuild the refugee camp — both the so-called New Camp, which sustained heavy damage, and the original, smaller Old Camp which was completely destroyed.

Little Arab financial support for UNRWA

So far UNRWA says it has received just $70 million, 88 percent from Western donations, which also make up 90 percent of funds pledged for short-term relief. To date, no Arab governments have pledged to the long-term reconstruction of the camp, the largest single project in UNRWA’s history.

“Sadly this is part of a pattern,” said Leila Shahid, a Palestinian representative at the European Union, in a recent editorial.

“Luxembourg donates more than any Arab government to UNRWA’s regular budget, while Norway gives more to the same budget annually than all Arab governments combined.”

In a bid to highlight the plight of the Palestinians displaced from Nahr al-Bared, UNRWA last week organized a rare tour to areas of the new camp. IRIN’s previous visit to the camp was in December.

Despair, trauma

Though many aspects of normal life, such as vegetable shops, Internet cafes and functioning electricity cables, had returned to some areas of the new camp (the old camp, controlled by the Lebanese army, remains off limits), the emotional scars among the population appear to run as deep as the physical scars on the camp.

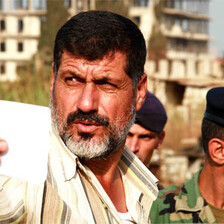

“Depression is increasing among patients,” said Mahmoud Nasser, chief medical officer for the camp, and head of one of two new health clinics opened by UNRWA since November.

“They are more aggressive and some are sinking into despair. We’ve had diabetes patients who stop taking their medicine because they don’t see any point in staying healthy.”

Nasser said his clinic was treating some 180 patients a day, many with skin diseases from the huge dust clouds that blow from the rubble of the camp. UNRWA is now providing 100 percent of medication for chronic diseases, like hypertension and diabetes, rather than its usual commitment of 50 percent.

Salina al-Aynen, coordinator for the Children and Youth Center, a kindergarten funded by an Italian non-governmental organization, and Save the Children, said many of the young children aged five to eight they host had displayed signs of trauma.

“After the nightmare of Nahr al-Bared we saw kids just walking barefoot through the streets. When they came here all were scared and some would prefer to be alone. But we help them overcome their fear through communal games and celebrating the good things in life.”

Discontent

Abed Najjar of the Nahr al-Bared Palestinian Popular Committee said discontent was growing among Palestinians returning to live in the new camp.

“The army doesn’t care about anyone. People are being harassed at checkpoints daily,” he said. “Reconstruction is very slow. They’ve promised to remove the rubble in the old camp five times now.”

UNRWA says rubble removal in the old camp is due to begin at the end of the first week of October.

This item comes to you via IRIN, a UN humanitarian news and information service, but may not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its agencies. All IRIN material may be reposted or reprinted free-of-charge; refer to the copyright page for conditions of use. IRIN is a project of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.