The Electronic Intifada 5 November 2002

Kathy Kern. (CPT)

Unlike my cellmates from Malawi and Russia, facing deportation — probably for overstaying a visa and prostitution respectively — I was being deported for working with a human rights organization.

That afternoon, the young woman at passport control had stamped my passport with a three month visa and sent me, as per the usual routine for suspicious characters, to a security person for further questioning. He laughed when he saw me, because he had interrogated me before. The next steps normally would have involved him asking me further questions, putting my luggage through a scanning machine and letting me go.

But this time, something on the computer caught the attention of the Interior Ministry. After several hours of questioning and leaving me to wait outside an office, Ministry officials told me they were denying me entry into Israel.

I refused to accompany the security people to my cell until someone answered this question: Given that I had entered the country multiple times in the last seven years, each time telling airport security the truth about my work, why were they deporting me now?

“I don’t care about your honesty! I don’t know why they let you in before! You may not enter Israel!” the Interior Ministry official said. I persisted in my demand for an explanation and he finally said, glancing at what looked like a police report in Hebrew on his computer screen. “You make many problems for soldiers.”

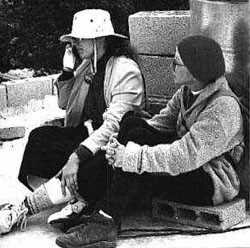

Kathy Kern and another CPT member sit on the roof of a Palestinian home in an attempt to halt an Israeli demolition. (CPT)

When Israeli airport security ushered me into the holding cell area and told my jailer why I was being deported, he noted the tears running down my face and said, “No! No! It is crazy here. You are good! You are good!” He then kindly allowed me to call an Israeli friend, Yaalah, although official deportation protocol permits a call to the U.S. Embassy only. She said she would notify my co-workers.

At 6:30 am the next morning, the police drove me across the tarmac to the British Airways jet and waited there in the vehicle, its lights flashing, until the plane taxied away.

The day after I got home, Yaalah called and told me that Israel’s Ministry of the Interior is on strike at the moment, which may have had something to do with my deportation. Representatives were denying entry to anyone who raised red flags rather than scrutinizing their backgrounds more closely.

Several days later, I wrote a letter to the Israeli Embassy saying that the work I do as a human rights activist actually enhances Israeli security, because intervening when we see Israeli soldiers and settlers brutalizing Palestinians helps decrease feelings of rage and helplessness that might be channeled into violent resistance, and because we support Palestinian groups using nonviolent strategies to resist the Occupation.

“If Palestinians believe their goal to end the Occupation can be accomplished nonviolently,” I wrote. “There will be many fewer dead Israelis. And fewer dead Israelis and Palestinians is something that my co-workers and I truly yearn for.”

I do not have high hopes that the Israeli authorities will allow me to return. Zeev Boim, a senior member of the ruling Likud party recently introduced a bill in the Knesset (Israeli parliament) that would make assistance by an Israeli citizen to the Hague International Court of Justice punishable by up to ten years’ imprisonment. The deportation of foreign human rights observers pales in comparison to the imprisonment of Israeli citizens for submitting evidence of war crimes to an international judicial system. But both actions beg the question, why is the current Israeli government afraid of people reporting what it is doing in the Occupied Territories?

Kathy Kern is a long-time member of the Christian Peacemakers Team (CPT) in Hebron. This week she was deported back to the US upon arrival at the Ben-Gurion Airport for her eleventh term of peacemaking service. She wrote an article about the experience for a local paper in Rochester NY.