The Electronic Intifada 9 February 2012

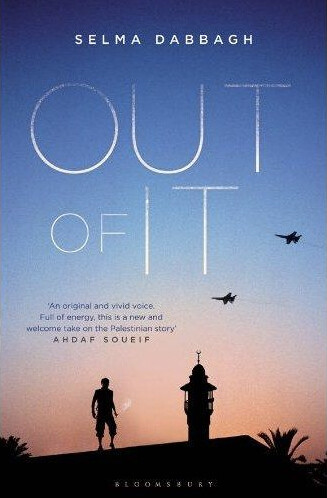

In Selma Dabbagh’s debut novel Out of It, 27-year-old twin misfits Iman and Rashid Mujahed try to find belonging in a contemporary Gaza groaning under Israeli siege and air strikes, and street battles between competing political factions.

The Mujahed family’s trials in Dabbagh’s fast-paced narrative encapsulate that of the Palestinian family at large — split by political division, secrecy and amputated (literally, in the case of Iman and Rashid’s heroic older brother, Sabri) by betrayal. The children of a high-ranking figure with the “outside” Palestinian leadership who has fallen from grace, the Mujahed twins were raised in scattered countries before peace agreements brought their family to Gaza.

Out of It is strikingly different from the story which one would expect to be told about Palestine, focusing on a family which has spent most of its time in exile. The Israeli occupation is felt by a menacing helicopter overhead and air strikes executed by anonymous pilots rather than dramatic scenes of incursion or checkpoints (though Iman has a humiliating experience at one when leaving Gaza). There are lots of characters with guns here, but they are Palestinians, and those guns are pointed at other Palestinians.

Contradictions within Palestinian society are shown through the characters’ struggles. Iman diligently tries to prove herself in tedious leftist Women’s Committee meetings, where competition rather than camaraderie is the prevailing dynamic. Iman is marginalized because she has only just “returned” to Gaza, and finds that the only thing she can contribute are servings of tea. Her desire to take more effective action sets her life in an unanticipated trajectory, taking her to the Gulf and later London.

Shadowed by family’s past

Meanwhile, Rashid, despite working at a human rights center, becomes increasingly apathetic politically and long-held grudges further alienate him from his brother and mother. He escapes from his non-future in Gaza by smoking marijuana until a scholarship brings him to London, where he is still shadowed by his family’s past.

The twins’ time in the Gulf and London makes for the richest narration, thanks to Dabbagh’s evocative description of Rashid and Iman’s new surroundings. In London, Rashid is brought to his English girlfriend Lisa’s family home, “as though she had brought home a particular piece of jewelry from a junk shop and could now, against a plain background, appreciate its particular panache” (113).

Meanwhile in the Gulf, Iman is stuck in a traffic jam with her father, “where middle-aged Western men stared hard at the stationary traffic, gripping their steering wheels as though they were about to be pulled away from them, women in black headscarves chewed gum with open mouths, East Asian women in the safari uniforms of the Chinese proletariat held toddlers in backseats, their foreheads slumped against the windows” (166).

Iman and Rashid’s characters are complicated and believable, and this reader wishes that more narrative care was spent on other characters — particularly that of their mother, who is portrayed bickering with a next door neighbor and obsessively pickling vegetables. One of the plot’s turning points is a revelation about the mother’s past that explains why the father abandoned the family. But because those two characters are not particularly developed, the plot twist falls a bit flat.

Power dynamic

Dabbagh also uses some of the characters to make points that come off as forced. Rashid’s girlfriend Lisa is at first presented as a well-meaning human rights activist who had volunteered in Gaza. But when Rashid joins her in London, a patronizing power dynamic develops between them.

This is compellingly shown in a tension-filled dinner gathering in which Rashid is expected by Lisa to perform on command by describing the despair in Gaza to impress the crowd, which includes a British government official. “Anger had built up in Rashid, talking about the situation, trying to give these people Gaza like it was chili on a saucer,” Dabbagh narrates (141).

This would be enough to show the dynamic between Lisa and Rashid — Rashid wanting a fulfilling relationship with Lisa, Lisa wanting him to serve a particular end. This is needlessly hammered home when Lisa responds to Rashid’s suggestion that a small grant from the British official be given to his friend Khalil, who is devoted to the human rights center in Gaza. Lisa says: “ ‘That’s just typical, isn’t it? So tribal, you stick up for your own little group. You just don’t get it, do you?” (143).

The patronization Western activists show toward the Palestinians with whom they purport to be in solidarity is demonstrated with more restraint through the character of Rashid’s fellow stoner roommate, Ian, who does his best to one-up Rashid’s knowledge of Palestinian history. “When faced with political questions of the type Ian particularly liked to concoct, Rashid never knew where to start. … Victim or propagandist, take your pick; Ian always forced him into one role or the other” (119).

While the character development in Out of It may be uneven, the plot moves quickly and Dabbagh’s unique sense of observation brings her story’s settings and characters to life. Iman and Rashid do eventually find their own sense of belonging, but not without their own complex personal struggles and not without understanding the truth of their family’s — and people’s — history.

Maureen Clare Murphy is managing editor of The Electronic Intifada.