The Electronic Intifada 8 November 2019

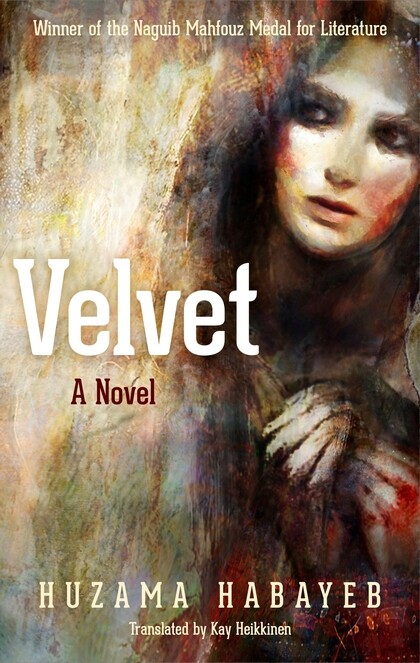

Velvet by Huzama Habayeb, translated by Kay Heikkinen, Bloomsbury (2019)

For many, refugee camps are a world apart. This latest novel from Huzama Habayeb, an award-winning Palestinian writer, goes some way in bringing that world closer.

The impressionistic Velvet portrays the claustrophobic world of Baqa’a refugee camp, established in Jordan in the wake of the 1967 War.

Split between past and present, the present action follows Hawa, a 47-year-old divorced mother, as she spends the day excitedly anticipating her forthcoming wedding. The retrospective describes Hawa’s disturbing upbringing, disastrous first marriage and unusual friendship with her teacher.

As in her previous novels The Origin of Love (2007) and Before the Queen Falls Asleep (2011), Habayeb commands multiple threads of narrative and perspective expertly. In making Velvet a tapestry of past and present, Habayeb provides a protagonist with substantial depth, making Hawa’s struggle against tragedy and malevolence all the more admirable and, ultimately, emotive.

World of violence

The world of Velvet is one in which beatings, assault and rape are common. As Hawa tries to make her way towards fulfillment, she repeatedly encounters people bent on stopping her by brutal means.

Whether it is at the hands of her father, grandmother or first husband, violence constantly interrupts Hawa’s growth. Her unbroken fortitude, the source of which is left somewhat unexplained, is nothing short of miraculous.

Yet this inundation of gratuitous cruelty can overwhelm the text, and the pain and pathologies harbored in its perpetrators, as well as the culture that enables them, is not adequately investigated.

Consequently, there is an unintentional displacement of emphasis: instead of allowing Hawa’s tenacity to shine through, the reader is often overburdened by inexplicable darkness.

People beat her because, well, people beat her. Such undiversified writing, where the characters committing the violence appear to exist only to do just that, leaves parts the novel underdeveloped.

It is a disappointing setback for what is, on the whole, a highly accomplished book.

Habayeb’s foil to the soul-sapping savagery is Hawa’s relationship with her mentor, Sitt Qamar. Qamar is a trend-setter, fashionable and sleek, and presents Hawa with ideas of sensuality and culture.

She teaches Hawa how to sew – a vital skill which gains her some independence – and she affirms life through her elegant ruminations about cloth, and its enigmatic effects on the senses.

Shared desires

It is this relationship that showcases Habayeb’s descriptive talent. As teacher and student luxuriate in the aroma of velvet, the author weaves in allusions to their shared desires and hopes:

“It’s the aroma of warmth, of dormant heat, of depth and expanse; it’s the aroma of well-deserved luxury, of pride and restraint; it’s the aroma of wishes and desire, of maturity, maturity of love and of age; it’s the aroma of clean flesh, of love suffused with yearnings and the sweat of lust.”

Moments such as this make the book bearable, saving it from gloominess.

Whereas Hawa’s abusers lack an inner voice or a contextualizing backstory, Qamar has both. In the presence of these two complex women, Habayeb’s writing is sensuous and sensitive.

She creates a world in which imagination matters, and although increasingly threatened by the surrounding violence, it is a world in which the reader longs to remain.

The lyrical Velvet has garnered much praise since its 2016 release in Arabic, winning the prestigious Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature a year later. We can expect, since its nimble translation into English by Kay Heikkinen, that the favorable attention will continue.

The subject matter is raw, making for compulsive reading. It undercuts the ignorance and misunderstandings of mainstream news. Overall, it is certainly worth a read.

Yet Velvet’s tendency for over-indulgence, stymied development of some crucial characters, and its depressingly anti-climactic denouement cause it to fall just short of the literary merit denoted by its accolades.

Michael Pritchard is a PhD student at Lancaster University working on Palestinian fiction and memoir.