The Electronic Intifada 12 October 2004

The 100 Shaheed exhibition catalogue

In Occupied Palestine, it is as if you live a dehumanized existence from the day you’re born. You are uneqal. You feel it everyday in how power is exercised. That relationship is rarely altered. You are second class and relegated to a Bantustan-like existence. When the people in power talk peace, you see the situation deteriorate. You see loved ones die, killed off by security forces. You learn to hate because you’re isolated and you know nothing else.

Today you can still see the broken glass of the picture, the bullet holes and a broken door left in the board room, curated like an art exhibit. The Sakakini Center has at different times received funding from the Japanese Government, the United Nations Development Program, the Ford Foundation, the European Union, and Dutch benefactors - hardly radical organizations in the grand scheme of things.

Director Adila Laidi explains that the role of culture evolves over time and raises to the public questions like the normalcy of the Israeli Occupation. If

Edward Said and Noam Chomsky argue that the role of the intellectual is to speak truth to power and Bill Moyers says the same of journalism, then what Laidi is arguing is much the same for art and culture in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

In the office next door, the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, known as the conscience of his people, is working on his literary review, Al Karmel, as he has since he used to edit it in Lebanon.

Laidi says that since the outbreak of the second intifada in 2000, there has been no normal life. And that as the role of art and culture develop as a means of expression in the context of the Occupation and the current intifada, the Sakakini Cultural Center has a duty to reach beyond the middle, educated classes.

Her view is that music, culture, art and literature still has the power to lift people up to dream and imagine when their humanity has been reduced to an

identity card. And by giving people access to these forms of expression, it can also reduce the gaps between those who are here and isolated with those who are in the Palestinian diaspora and the outside world. It is also a place where people can channel their anger and creativity.

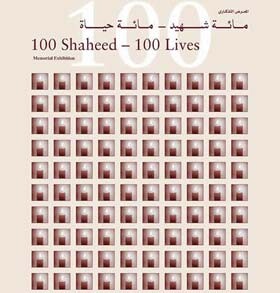

Laidi sees the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center as a place to nurture Palestinian visual artists. She was also involved with curating the controversial 100

Shaheeds exhibit which memorialized the first 100 Palestinians who died in the second intifada.

In the introduction to the exhibition catalogue, Laidi, as the editor, writes, “one of the project’s goals was to give back to each shaheed (martyr) his or her individuality …[hence] each [was given] his or her own personal space, featuring his or her name, photograph and personal object. The Shuhada [are] also presented in order of age. The objects and photographs … speak for themselves, on their own terms, going beyond death to recreate a life without the clutter of text or obtrusive display devices.” The exhibit has gone abroad and generated much discussion.

For now, the Sakakini Cultural Center is limited in their ability to go beyond Ramallah, hampered by the same security restrictions as everyone else.

Adila Laidi says, “We need to have more rooting in the community that does not currently consume culture, and have more popular forms which they can affiliate with.”

Am Johal is a freelance writer recently working in international advocacy with the Mossawa Center, the Advocacy Center for Arab Citizens of Israel, and is currently in Canada working on the book “The Grand Dissonance” about the Israeli/Palestinian Conflict.

Related links: