The Electronic Intifada 5 October 2017

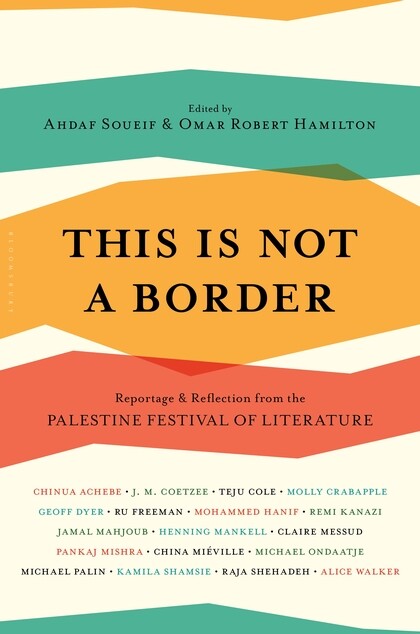

This is Not a Border: Reportage and Reflection from the Palestine Festival of Literature, edited by Ahdaf Soueif and Omar Robert Hamilton, Bloomsbury (2017)

This is Not a Border is an anthology of writing that celebrates the 10th anniversary of the Palestine Festival of Literature, or PalFest – a “cultural roadshow” which was established in 2008. Since then, the annual week-long event has brought about 200 authors and industry professionals to both the occupied West Bank and, in some years, the Gaza Strip.

In the introduction, the Egyptian novelist Ahdaf Soueif states that PalFest was founded in response to a question: “Could we organize a small group of writers to travel to Palestine, experience the situation there for themselves and do events that Palestinians want?”

Soueif’s question animates the 60 essays, statements, reports and poems that follow. Some are by writers who experienced life in Palestine for the first time by attending the festival.

William Sutcliffe – the British author of The Wall, a novel set in the West Bank – writes:

I thought I had a good understanding of the West Bank wall before flying out to Amman to join the PalFest 2010 group … Nothing I had read about the injustices and cruelties of partitioned Hebron prepared me for the physical, emotional and intellectual impact of walking down the shuttered and abandoned high street of the old town.

Also included are reports by writers based in the West Bank and Gaza – such as Raja Shehadeh, who arranges a walk near Ramallah for the festival’s authors. Reflections also come from those who have long connections to the Palestinian cause, including the American novelist and poet Alice Walker.

While some contributions recount a visit to PalFest, others explore wider issues.

Victoria Brittain writes movingly about the “bleak” state of mental health in Gaza. Rachel Holmes, who was born in South Africa, recalls childhood memories of apartheid, which returned as she encountered what she calls “the familiar geography” of occupied Palestine: “The recognition was instinctive, intimate and sickening.”

Not an ordinary festival

Anthologies often get a bad name for only offering excerpts from longer works or short pieces that do not reveal a writer’s full talents. But PalFest is not an ordinary festival and this is a surprising collection.

As the novelist Deborah Moggach writes in a short essay titled “Diary”: “Literary festivals are [normally] where writers go to whinge about their agents and their editors, about traveling all day to be greeted by an audience of three and a dog.” Moggach notes that PalFest throws this “into relief” since Palestinian writers’ lives are “astonishingly hard.”

In another essay, novelist Kamila Shamsie recounts the story of the Palestinian poet Kamal Nasser, who was killed by an Israeli commando unit led by the future Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak in Beirut in 1973.

Shamsie recalls discovering that Nasser was “shot in the mouth, and also in his right hand, the writing hand.” She notes: “When I read those words about Nasser, I had to put the book down, stand up and physically walk away from it for a while.”

There can be few starker illustrations of how dangerous the work of a Palestinian writer may become.

The work of PalFest is designed to keep open spaces where writing and speaking about Palestine are possible, and also to express solidarity with Palestinian writers who persist with their work under extraordinary duress.

Momentarily transformed

The difficulty of accessing a wider artistic community is explored by the Gaza-based novelist and short story writer Atef Abu Saif, who recalls: “When I was at school one of our English-language classes was writing a letter to your friend abroad inviting him to visit you in your hometown.” He shows how little purpose this academic exercise serves when visitors from abroad can seldom access Gaza.

Soueif notes that the festival’s organizers wanted the visiting writers “to travel in the same manner as its Palestinian audience.” Many of the contributors recount entering the West Bank via the Israeli-controlled Allenby Bridge from Jordan rather than through the airport in Tel Aviv.

Brigid Keenan, a founding trustee of the festival, writes: “Laughter ceased at the Allenby crossing. All the people in our party with Arab names were stopped – in spite of holding US or British passports. It was four hours before our friends were released.”

The English-Palestinian novelist Selma Dabbagh reports being part of an “Egyptian Delegation” of PalFest that visited Gaza in 2012.

Dabbagh describes the Rafah crossing as a “hateful space,” but writes that it was “momentarily transformed” by music when she was there, as an oud player from the Egyptian band Eskenderella was also waiting. He was promptly told to stop playing and leave, as he did not have the correct papers.

The anthology frequently portrays art disrupting the daily oppressions of the occupation, and Dabbagh’s experience at the border is not the only time in this book that such art is silenced as a consequence.

Thus Remi Kanazi, a New York-based poet, writes of the limits of his art:

this poem

will not end apartheid

my words, no matter how beautiful

clever or carefully strung together

will not end the occupation

Yet a poem by the British-Egyptian writer Sabrina Mahfouz speaks beautifully, in answer, of what poetry might do:

Let’s be the protectors of poetry

let’s pull bricks down

with the trick of words

and build them up again

when the sky no longer burns shadows

where we once spoke.

Silence is a language

The anthology also includes vignettes from the workshops that PalFest authors were asked to lead with young Palestinians. The Pakistani novelist Mohammed Hanif reports that among his apprentice writers, “There was anger over occupation, but more anger over why we must always be telling this story.”

Jeremy Harding, a contributing editor at the London Review of Books, queries a young woman’s desire to use mime in response to a writing exercise. “We believe that silence is a language,” she replies.

It is a serious limitation to the anthology that it includes these reported voices, but no poems, reports or essays that emerged from the workshops. An anthology that mixed established writers with new Palestinian voices would have been a more radical enterprise and might have better reflected PalFest’s mission.

Nonetheless, the writers included form a powerful community and their contributions are arranged with care. An echo in one piece will reverberate unexpectedly two or three essays later, while tales of everyday brutality accumulate.

It is an appropriate way to document the repetitive and cumulative impact of life under occupation.

Responses to chaos

The final, and longest, contribution is by the novelist and filmmaker Omar Robert Hamilton, the anthology’s co-editor and driving force behind the festival. In his essay, he makes a refrain out of the repeated instruction for the writers to “Get on the bus” as they visit five locations in the week during PalFest: Haifa, Jerusalem, Ramallah, Hebron and Nablus.

The piece combines Hamilton’s acts of witness with the stories he hears around him:

We need new words if we are to feel again. The bus climbs from the Dead Sea. The audience waits in Ramallah. Our host in al-Khalil is dead. I don’t want to cry going through Qalandiya any more. I don’t feel anything.

… The bus climbs. A bullet punctures a lung on Mount Calvary.

We have seen all this before.

The bus climbs. A body hangs limp from a tree above Abraham’s tomb.

Strange fruit.

Hamilton skillfully interweaves different voices and experiences, which are almost overwhelming, into something like a prose poem. It is a fitting conclusion.

The American novelist and Nobel Prize winner Toni Morrison has written about literature and engagement in a book subtitled with these themes:

I have been told that there are two human responses to the perception of chaos: naming and violence. … There is however a third response, which is stillness. Such stillness can be passivity and dumbfoundedness; it can be paralytic fear. But it can also be art.

Many of the writers in This is Not a Border speak of being dumbfounded by what the festival showed them; several describe moments of fear. Yet it is clear from these contributions that PalFest does more than present writers to Palestine or vice versa.

This anthology, like the festival it celebrates, strives to name the obscenities that are carried out against the Palestinian people.

Teju Cole contributes an incisive essay on the topic: “We must begin by calling things by their proper names. Putting a people into deep uncertainty about the fundamentals of life, over years and decades, is a form of cold violence.”

The anthology also seeks to conjure moments of stillness against the odds. The difficulty of that task is caught in Hamilton’s beautiful closing essay, which, like the anthology itself, ranges between anger and something close to prayer.

This book is not only an exhibition of writings from a festival; it is a work of art in its own right.

Tom Sperlinger is Professor of Literature and Engaged Pedagogy at the University of Bristol, and the author of Romeo and Juliet in Palestine: Teaching under Occupation.