West Bank 17 July 2003

A Palestinian truck driver tries to circumnavigate an Israeli roadblock in Azzoun, east of Qalqiliya. The town is completely encircled by Israel. Around 90,000 Palestinians live in the Qalqiliya area.

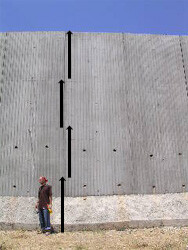

An international stands next to the Apartheid wall. 6-feet tall, he is dwarfed by the 25-foot-high wall (arrows adjusted slightly to account for perspective).

The family lost most of their farm land and orchards in 1948, during Al Nakba (the Catastrophe), when Israel took most of the land that was known as Palestine and over 800,000 Palestinians were expelled from their land and made into refugees. Since the construction of the Apartheid Wall, the family now cannot even get to the land that they were able to keep after 1948.

When we asked him about the U.S. backed Road Map for the Middle East, the father of the family said, “All of these talks and agreements — this is just for the media. I do not want to hear it on TV. I want to see it on the land.” Almost every day here in Palestine, as we are witnessing yet another example of the injustice of the Israeli occupation, at least one local will make similar comments to our group about the Road Map and the talk of “peace”.

In the last five days I have traveled to Nablus, Ramallah, Tulkarem, and Qalqilia, and I would like to share with you what is happening on the land, so that you will know what the media, the U.S. government, and the Israeli government are not saying.

Nablus

Some things have improved for Palestinians in Nablus: the regular 24-hour curfews that confined Palestinians to their homes for most of the day for weeks at a time, which persisted from the spring through the summer and into the fall of 2002, have ceased for now. My friend and local organizer of nonviolent resistance to the occupation, Saif, described to me the other day how the curfews were stopped in Nablus:

The children wanted to go to school and the education department did not take responsibility for these students and did not open the schools for them under the positions of tanks and curfew all the time. So the students with the local communities and the parents opened local [neighborhood/home] schools and then after a while [the people said] “No, we don’t want local schools, we want to go to our [regular] schools. We want to study with our friends from different areas and our teachers. And then the teachers with the parents with the local communities with the students took responsibility over the schools. The parents and students challenged the authority of the occupation!And the Israeli occupation forces did not accept this. They opened fire on children, they shelled schools, they shot students, they arrested students, they arrested teachers, they killed, but this did not stop these students from going to school. They continued going to school and this was one of the reasons that all of the community — everybody — decided to break the curfew, to go out. The schools opened, the teachers went, the students went and they needed transportation, so the taxis started to work and they started to go and pick them up from the roadblocks. The people went to school, they moved in the streets and so they wanted to buy things and the markets started to be open for those people.

Then the people thought, “Oh wow, the market is open, I’m going to buy something for my family,” so the people themselves started leaving their homes and going out and buying stuff even if the tanks were in the streets moving all around the houses. The Israeli army attacked taxis, destroyed cars, and killed drivers, but this did not stop the taxis from working. The occupation forces came to the market, to the stores, crushing them completely. The owners would come and repair their stores, and if they were arrested, their son or relative would come and repair the store and open it again. The woman, if they arrested her husband, she would come and repair the store and open it.

And this is the reason from this time until now, that the Israeli army leaves us alone and does not enforce the curfew on the street. And if there is a military operation in one area, just a few meters from the soldiers the stores are open and the people are in the streets, just looking at the army unfazed. This brand of courage didn’t come out of nowhere. It came from 55 years of occupation and 55 years of challenging the occupation. If you go inside a refugee camp and ask a little kid, “Where are you from?” he will not say “I am from Askar refugee camp.” He will say something like “I belong to Jaffa — my family came from there in 1948. I live in Askar.” This will happen in any refugee camp you may go to.

The positive changes in Nablus have come from the resistance of the people. Sadly, although the curfews have been lifted, the checkpoints continue to strangle the movement of Palestinians between Nablus and all of the surrounding villages that depend on Nablus for work, school, medical treatment. It is hard for me to imagine how there can be talks about “peace” when the movement of tens of thousands of Palestinians is dependant on the whims of Israeli soldiers every day. Palestinians must have written permission from the Israeli government to go back and forth between the villages and Nablus, and even this does not guarantee the soldiers will allow when to pass. Last week in Nablus I spent two days at the Beit Farik checkpoint which is the only way into Nablus for five nearby villages.

At Beit Farik, 25 men stood waiting in the sun to return to their villages from Nablus for over 5 hours. The line grew from 25 to 50 men, but the soldiers ignored them, only allowing one or two men to pass every twenty minutes until late in the day. Eight of the men were singled out. Their IDs were taken from them and they were detained at the checkpoint for hours until the soldiers decided to return their IDs and let them leave.

A young woman and her brother were trying to get to the University in Nablus and chanced driving around the checkpoint in order to avoid the wait and the possibility that they would not be allowed through. A settler police jeep caught them on the side road and forced them to drive to the checkpoint where their car was taken and they were forced to wait for at least one hour until the soldiers decide to return the car and allow them to go to University.

Many other cars, including taxis, tractors, and trucks loaded with hay have been confiscated by the soldiers for everything from attempts to drive around the checkpoint or because someone took longer to leave and return than he promised the soldier. One man we met has not been able to get his car back for over a month. The standard “punishment” as the soldiers themselves call it, is keeping Palestinians’ cars for one week. The soldiers at this checkpoint have a grocery bag full of Palestinian car keys.

Water trucks with permits to take water to villages who have no access to safe ground water are forced to wait for hours with no explanation as to why they are not allowed to pass through the checkpoint.

Three women from Jenin were allowed to pass the checkpoint. They attend the University in Nablus and are studying Industrial Engineering, Information Technology, and Psychology. Their brother, who also studies at the University and who is going to graduate in two days, was not allowed to pass through the checkpoint. Tired of waiting, he decided to go around through the olive groves — a very dangerous choice — and his sisters worry for his life.

From Ramallah to Tulkarem

Palestinians cross a barbed wire fence in Ramallah. (Ronald de Hommel)

On July 3rd, we awoke at 6:30AM in Ramallah in order to arrive in Tulkarem no later than 10:00AM for a demonstration against the Israeli Apartheid Wall being built on farmers land throughout the western edge of the West Bank. We had to walk for thirty minutes to the outskirts of Ramallah because of two large roadblocks built by the Israeli occupation forces. Anyone trying to enter or leave Ramallah on the Northern edge of town — workers, students, old men and women, mothers with small children — must walk a mile between the roadblocks that dips into a ravine and then back up.

Thousands of Palestinians must cross this stretch of road in both directions every day. On the other end of the roadblock, we found a service taxi to take us most of the way to Tulkarem. After passing through beautiful terraced hills of olive trees tended by generations of Palestinians, at least 5 Israeli settlements, and two Israeli checkpoints (where the soldiers were much more interested in the local Palestinian ISM coordinators’ IDs than the internationals), we came to a locked gate close to the town. The Israeli army has constructed the gate to prevent vehicles from crossing into Tulkarem on this road.

An Israeli gate controlling access to Qalqiliya.

Tulkarem

Palestinians demonstrate against the occupation.

Currently there is only one legal way in and out of the city — the checkpoint, and a small number of entrances that are often guarded by soldiers and will be closed off permanently soon. The family I mentioned earlier who lives near the Wall, described Qalqilya, “It is a jail with one gate. Qalqilia must be the biggest prison in the whole world.”

A sniper tower on the Wall.

When our group of internationals and our local coordinator arrived at the checkpoint, the soldiers did not want to allow us to enter. We waited and attempted to negotiate our way into the town for hours with no success. As usual here, at a little after 6:00PM the soldiers closed the checkpoint. At least fifty Palestinians were still waiting at the checkpoint or had arrived shortly after the checkpoint was closed.

All hoped to return home that night. The soldiers were refusing to let them return to their homes and families and screaming at them to leave the checkpoint. Some men argued with the soldiers and the soldiers responded aggressively. The soldiers marched up to the Palestinians who refused to leave and put their faces centimeters from the Palestinians faces and screamed at them. One soldier was especially aggressive, kicking stones at a young man and screaming in his face, while pushing and grabbing Palestinians.

This soldier charged screaming at one Palestinian and was preparing to beat him, when his captain pulled him back, possibly because of the circle of internationals witnessing this abuse. After about one hour of this, while a group of internationals were discussing the situation with the soldiers, the Palestinians began to walk through the checkpoint in a large group.

This time the soldiers let them go. We heard the next day that another group of Palestinians came to the checkpoint at 8:00PM and were not allowed into the town until the soldiers switched shifts at 11:00OPM. Our group was not allowed into Qalqilya and at about 7:00PM we went to one of the few remaining alternate entrances to Qalqilia where the Apartheid Wall has not yet been completed.

These entrances are deemed “illegal” by the Israeli military and when we arrived there was an armored personnel carrier with four soldiers blocking the way. While we negotiated with the soldiers to allow us into the town, a young boy (possibly 14-years-old) came on a horse trying to leave Qalqilia for his home in the village across the road. Another group of Palestinians wanting to go home to Qalqilia gathered across the road, watching us negotiate with the soldiers.

I asked our local Palestinian coordinator if we could negotiate for them to enter the town also, but it was almost dark and he felt that we could ask the soldiers about them, but should not push the issue and that we should enter the town if the soldiers allowed us. When the soldiers finally consented to allow us into the town, we asked about the boy on his horse and the men waiting across the road, but the soldier refused to let them pass. We entered Qalqilia, one local and 8 strangers with the privilege of international passports, while 40 locals were stuck to wait until the soldiers left or forced to find another way home. I felt sick to my stomach.

A section of the Aparthied wall, with a sniper tower.

Imagine if you were told by the soldiers enforcing the military occupation that you had to come home before 7:00PM every night. Imagine if your family’s survival depended on a farm and that the farmlands were confiscated in order to build the wall which imprisons you.

When the media, the U.S. government, or the Israeli government talk about the Road Map, do they mention the Apartheid Wall that the Israeli government continues to build all along the western edge of the West Bank? Do they mention the thousands of more acres of Palestinian land that the Israeli government is confiscating? Do they mention the countless checkpoints, roadblocks, and locked gates that the occupation continues to impose on Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza?

Despite all of these injustices the Israeli occupation impose upon the Palestinians in Qalqilia and all of Palestine, one young man here, Mohammad, described his community’s determination to stay in Qalqilia, “We believe in this land, this is why we don’t leave. This is my land, my father’s land, my grandfather’s land. I will not leave it. I will not even think of leaving it.”

Brooke Atherton is currently with the International Solidarity Movement in Palestine.