Palestine 11 June 2006

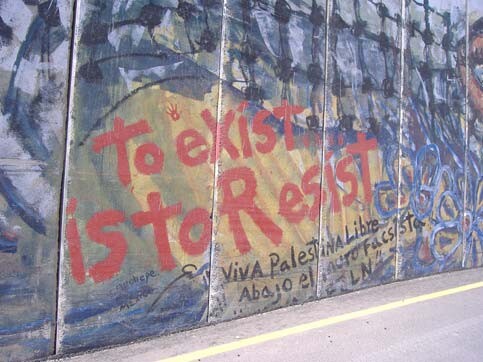

Graffiti, “To exist is to resist,” emblazoned upon the Apartheid Wall in Bethlehem. (Christopher Brown)

“Israel’s High Court of Justice Wednesday began a review of interrogation tactics by Israeli security services mainly applied to Palestinians that have widely been condemned by human rights groups.

“The High Court’s review of tactics by Israel’s Shin Bet security service began a day after a scathing Amnesty International statement said that Israel is the only country in the World to allow what amounts to ‘legalized torture by it’s police.

“Israel does not contest reports that Shin Bet agents have used tactics such as violent shaking, sleep deprivation, confinement in tiny spaces, and exposure to heat and cold in their interrogations of mainly Palestinian security suspects, but it denies that the use of physical pressure on prisoners is systematic and says it is only applied in so-called ‘Ticking Bomb’ cases in which it is imperative to extract information to avoid loss of life.” -David Gollust, VOICE OF AMERICA, 13 January 1999

A friend of mine sent me an article that he found on the web. In the email he wrote: “This ought to bring back memories for you.”

He was right.

While I lived in Palestine for three years, I had many conversations with both Israelis and Palestinians about the issue of torture. The conversations always varied and they never became dull.

I heard from many Palestinians who had been tortured. I also heard from some Israelis and Palestinians who felt that certain forms of torture are useful.

I always sat and listened to them being attentive and polite. But every time I got into one of these conversations, I would think back to a certain time in my life that deeply affected my view on the subject.

June is Torture Awareness Month. I find it ironic that June was chosen as the month, because June holds a very special and yet painful part in my life that I will never forget. For it was on 4 June 1990 that my life took a radical change.

4 June was the day that I was “detained” by the Security Police in South Africa for violating a curfew. I remember a Caspir (riot vehicle) rambling by me down a dusty road. It was the first time I had seen such a machine. It was huge standing nearly 20 feet high and composed of solid bulletproof metal. As I watched this object of law and order courtesy of the apartheid state ramble on, I wondered what sort of destruction this machine wreaked upon the children who first fought against it on 16 June 1976 during the student uprisings.

Suddenly, the Caspir turned around and headed back down the road towards me. I walked on thinking that they wouldn’t bother me.

I was wrong.

The Caspir came to a screeching halt in front of me. Several policemen appeared from the rear of the vehicle and one of them, an a white policeman approached me. In Afrikaans, he asked me where I was going. Because I can speak the language fluently (in addition to four other South African languages) he assumed that I was a local. After a bit of questioning, he told me to get into the back of the Caspir. When I inquired why, he spoke to me sharply:

“Don’t get cheeky Kaiffer (the South African equivalent of ‘nigger’) get in the back!”

That day was the last time I would see natural sunlight for the next 550 days.

I wasn’t under arrest. I wish that they had arrested me - at least then I would have had rights. The right to see a lawyer; the right to let my family and friends know where I was and how I was doing, basically, the chance for due process.

But there were two problems with this scenario. The first was that I was not under arrest, I was being detained; this meant that I had no access to a lawyer, no chance to contact anyone about my whereabouts, and the detention could go on indefinitely, under the Terrorism Act of 1967, and the most chilling part was that many activists died while in detention.

The reasons for their deaths varied, but I must admit they were creative based on reports given by the Security Police. Usually they were listed as “accidents”:

As fate would have it, I avoided these “accidents”. But the Security Police had something else in mind for me.

I had the misfortune - or joy, depending on your view - of being put through “sleep deprivation”. Many states in the world today do not consider this torture.

Indeed, in Israel, to this day sleep deprivation would be classified as “moderate pressure.” We in the West would call it torture-light.

Let me be blunt, there is nothing “light” about torture.

Sleep deprivation can and will play havoc on a person over time. Imagine being questioned for 15 hours straight and then, after this has concluded, being allowed to go to bed. Now keep in mind, no one puts a hand on you during the “questioning”. No one is yelling at you or being abusive in a way we would think one could be. However, you are made to stay awake during this entire process and there are constant questions and accusations hurled at you.

Now let’s say you are headed back to your cell to get some sleep. I mean, you deserve it, heck you’ve been chatting for the last 15 hours, and you’ve got it coming. Right?

But there is a slight problem when you get to your cell. For one, the lights are kept on while you’re trying to get sleep. To make matters worse, the light is coming from a bright fluorescent tube that is suspended over your bed. Add to this, music blaring from down the hall of your cell while you are trying to get some shut-eye.

Good times.

Well, no sooner than you lay your head on your flea-infested pillow, and actually manage to somehow fall asleep, someone comes to open up the cell door and says:

“Come on, get up, you can’t sleep forever. We want to talk to you!”

You wake up confused, disoriented. You look about asking yourself, “Didn’t I just get back from ‘talking’ not more than 20 minutes ago?” But regardless of what time you got back, you have to go again. Besides, all they want to do is talk to you. Nothing more.

Right?

The truth is that there is so much more. Over time, one begins to get delirious. One begins to imagine things constantly; you talk to yourself, argue with yourself. You begin to have hallucinations. In some cases you begin to lose control of bodily functions. And all the while you lose track of time and space. A day seems like a week, a week seems like a month, and so on.

Don’t be too concerned; you’re not always being “talked to” for 15 hours straight. Sometimes it’s only for 4 hours on and one hour off. Maybe they want to have a late night bull session with you from 3 am to 9 am, then let you go back and rest for a little while as AC/DC wails in the background and jailers laugh and roar with their drunken buddies.

Not bad, you say?

Well, imagine that this sort of treatment is kept up for over a period of time like a year and a half. Imagine that every once in awhile, they tell you that you’re going to be released the next day, and they tell you to gather your things. You’re going home! Never mind that you haven’t given them any useful information that’s not important. What is important is that you’re outta there!

Then imagine, that you have what little they’ve allowed you to have in your cell (Usually a Bible), and your walking down a corridor. You stop at a desk and they have papers for you to sign to be released.

It’s legal.

They have your name on the papers and everything. You read through them making sure it looks okay and you sign. You’re about to leave this God forsaken place when suddenly a man walks up to you as you are approaching the main doors to wherever they have been keeping you and says:

“Are you Khaya Chris Brown?”

You nod in agreement.

“You’re being detained for 90 days under the Terrorism Act.”

And off you go for another round of conversation with your jailers. Not knowing when this “light” form of torture is going to end. Not knowing when your name will be on a report that says: “Prisoner hanged himself in his cell.”

This is what happened to me over the course of my 550-day incarceration. You might say I was one of the lucky ones - I didn’t end up dead.

And if you thought about it this way and have never experienced torture yourself, I suppose you’d be right.

But explain to me how lucky I was when after three months, I had been “questioned” so many times by the Security Police, and become so disoriented, that I began to believe that there was another man who was being tortured in a cell right next to me.

I was sure there was, because he and I had many conversations about our situation. He told me about his family, girlfriend, where he went to school. In fact, during my darkest hours he would tell me to be strong and not give in. Now imagine that no one had been anywhere near my cell who was also detained at the same time as myself. I had dreamed up my imaginary friend out of necessity for what little sanity I had left.

Maybe I was lucky when I counted ants in my cell and kept them as pets, thinking them dogs instead.

Those who would proclaim that there are times when torture is necessary never seem to be the folks that have gone through any form of torture, whether it is “hard torture” or “torture light.”

I recall a quote from the email my friend sent me. Moshe Fogel, then an Israeli government spokesman, said:

“Torture is illegal in Israel. There is no excuse and there is no way that anyone can employ torture or tactics which involve torture in interrogations, even with wanted terrorists. What is allowed, in certain unique, extreme circumstances - What we call ‘Ticking Bomb’ situations - is moderate pressure…”

I’ve been in a number of support groups with other survivors of torture and we all arrived at the same conclusion. None of us, no matter how bad our experiences - no matter if we received water-boarding, electric shocks on our genitals, cigarette burns on our breasts and scrotum, exposure to extreme heat or cold, and sleep deprivation - none of us would wish torture on even our worst enemy.

So, maybe I am lucky. Maybe I should be grateful that I didn’t die at the hands of my jailers like so many before me or since. But, I’ll tell you now, no matter what anyone says; a part of me died on 4 June 1990 and I wish I could get it back.

That doesn’t sound very lucky to me.

Christopher Brown is a radical grassroots journalist who grew up in South Africa for the first eight years of his life under apartheid. In 1990, he returned to continue the struggle against racism and oppression. He spent 550 days in solitary confinement in a South African jail under the 1967 Terrorism act. While detained, Brown was repeatedly tortured. In 1992 he and several thousand other detainees were freed in part due to a massive letter writing campaign led by Amnesty International. Brown, to this very day, is card-carrying member of this human rights organization.

Related Links