The Electronic Intifada 14 November 2024

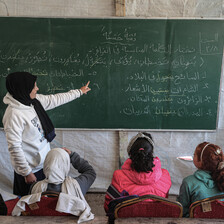

Giving classes during genocide to local children gave the author some of her most “meaningful moments.”

What do you do as a teacher when there are no schools, but hundreds of thousands of school children in need of education?

In May, I came up with my own response to Israel’s genocidal onslaught on Gaza’s education sector.

With every university and 80 percent of schools damaged or destroyed in little over a year, and remaining schools transformed into shelters for the displaced, my options were limited.

So I decided to start giving classes in a small room in my own home in al-Shujaiya in the north.

And I decided to start every day by reciting these lines, to encourage and inspire my students.

Bloom, bloom, bloom,

Like the rose

We will bloom.

Shine, shine, shine,

Like the stars

We will shine.

It is children who have paid the highest price of Israel’s genocidal aggression. Forty-four percent of verified killings are of children, according to the UN, while 17,000 children have been left unaccompanied, either because all their relatives have been killed or they have been separated from adults in their families.

Of Gaza’s 625,000 school age children, none have received a formal education since last October.

Creating a place to learn

I felt I had to find a way to bring back learning and happiness to at least a few of these children.

I took out my old chalkboard and put it on a wooden stand in my dining room, which had a table with eight chairs. I formed four groups of eight students from kindergarten through sixth grade.

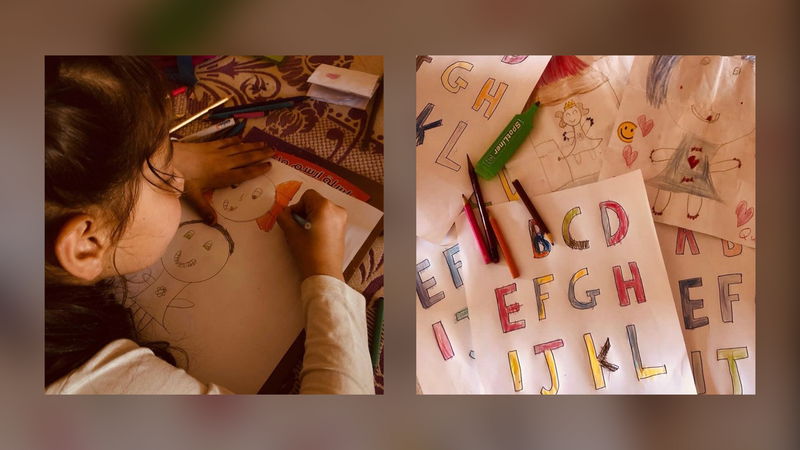

I planned to give them English lessons.

During our first class, 32 students from my neighborhood came. I asked the students their names and ages, outlined our schedule together, and talked with them about what we would be studying.

Their excitement was palpable; they were eager to have a teacher and lessons after eight months without any education.

During our second class, I noticed that the students brought knapsacks, water bottles and an array of pencils. Some of the school supplies had been scavenged from the rubble of their homes; others gifted to them by kind neighbors.

I had to develop my own curriculum, selecting topics I believed would interest the children.

The most obvious, of course, was what was happening around them, so one day I asked my students to write stories about the Israeli genocide and their dreams and hopes amid all the carnage.

The following day I was astonished by their creativity. I felt a profound sense of pride in myself and my students for our courage and commitment to learning.

And I felt deep sadness for these children, who should not know what they have learned in the past 13 months.

Wrote Mariam, 8:

“I don’t know where my friends are. I miss them so much, and I miss my days in school with them. I love studying math and science. Now, I’m so sad and tired without school.”

Jory, 8, remembered her sister:

“I can’t believe that my sister is in the grave now. What did she do to deserve this? She was just smiling and playing with us when they killed her. I miss her so much.”

Students tell of love and loss

“Are we children like other children in the world?” Marah, 5, wondered. “Why do they kill us? I want to play with my toys, not die. I miss my teacher. I miss all my friends.”

After each class, I encouraged the children to stay a little longer so they could draw, play games. and sing songs. These were moments of joy amid the overwhelming loss and suffering they had endured.

I encouraged the students to share their dreams and think about how they could help our country and its people during these difficult times. I encouraged them to tell the truth and to seek justice in a world that often feels dark and unfair.

These were some of the most meaningful moments of my life, even with the heavy bombardment all around us.

Unfortunately, after six weeks of classes, the Israeli military invaded my neighborhood in June. I was displaced and could not continue teaching.

It would be two weeks before I was able to return to my home. But by then, many of my students had themselves been displaced. Most of them remain displaced, living in makeshift shelters or with relatives.

When I see them, I often ask why they stopped attending my classes.

“It is no longer safe,” is the universal response.

They are simply afraid. They’ve seen too many children killed in the streets.

I believe my little school provided a glimmer of hope in these awful circumstances. I hope they allowed these children to express themselves and dream of a better future.

As soon as I can, I will start up these classes again. As a teacher, it is my duty to help children bloom, even – perhaps especially – amid the ashes of our homeland.

Nadera Mushtha is a teacher/writer in Gaza.