Rafah, Egypt, Rafah 26 September 2005

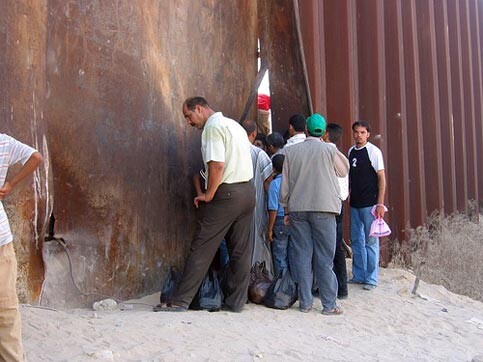

Palestinians crossing through to Egypt from Gaza’s abandoned ‘Philadelphi corridor’. (Photo: Leila El-Haddad)

We were standing there on the edge of what was a graveyard of man and stone - the no man’s zone in which many Palestinians had lost their lives at the hands of the Israeli army.

We were seven friends and coworkers, some of which had come to verify the rumors in Gaza about unchecked crossing into Egypt, while others were tourists, making their very first trip outside the Gaza Strip.

On the night of Sunday, September 11, two days before our trip, the last Israeli soldier left the Gaza Strip, ending 38 years of Israeli military occupation. All of a sudden, Egypt was open to Palestinians.

Trade, curiosity, meeting relatives or all these reasons together were driving thousands of Palestinians to cross the former death zone and the eight-meter-high metal wall into Egypt.

We had not expected to see such an enormous outpouring into the Egyptian territories. People were scaling walls, barriers and at points burrowing their way through, in an effort to reach the other side. Parents passed children over walls and others hired drivers to take them to the border to avoid the colossal traffic jams.

Officials on both sides of the border estimated that 100,000 Palestinians had crossed over to Egypt, but eyewitnesses believe that this figure is a gross underestimation.

“Come on! Let’s cross. I want to have fish for lunch in Areesh,” shouted a friend, encouraging us to cross and travel 40 kilometers to the coastal town of Areesh, which is the capital of northern Sinai.

As we jumped the 150-centimeter fence that separated Gaza from Egypt, we were greeted by Egyptian officers, some of the 750 men deployed along the border as part of an agreement with Israel.

While many Palestinian men, women and even children were making the leap into Egypt with us, others were standing on the wall and throwing back into Palestinian territories boxes of cigarettes and other goods purchased cheap in Egypt, goods that they hoped would make them a hefty profit once sold in Gaza.

Some Palestinians took advantage of the porous border to smuggle across tax-free cigarettes. (Photo: Leila El-Haddad)

On another part of the fence, relatives were hugging and kissing each other at their first reunion in over 10 years.

Um Rami, who lives in the Palestinian part of Rafah, greeted her sister Mariam with tears of joy and ululation. The sisters have been separated for more than 12 years, when the city of Rafah was divided between Gaza Strip and Egypt.

“How are you, my dear sister? I missed you so much,” Um Rami cheered, her voice choking with tears.

Leaving these emotional scenes behind, we reached “Egyptian Rafah”, a small town with a similar architecture to the “Palestinian Rafah”. It was indeed a city divided - only the license plates of cars revealed where you were.

The streets were full of curious Palestinians of all ages, asking for directions to Areesh. Fortunately, we managed to convince a pickup driver to take us as near to Areesh as possible. He agreed to take us to a nearby village called Sheikh Zewayyed.

We drove on roads snaking between vast expanses of farmland and sand dunes. It seemed as if we had never left Gaza. “It’s so similar to Gaza’s terrain,” said one of the passengers. “But it’s by far larger,” commented another.

But some 10 kilometers later we saw clear signs of being on Egyptian soil.

The village of Sheikh Zewayyed was dotted with posters of Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak and banners supporting his election for another term - leftovers of the first multi-candidate presidential elections that had taken place in Egypt a few days earlier.

The market area of the once-tranquil Sheikh Zewayyed had changed drastically into a city-like terminal filled with pickup trucks and buses packed with eager Palestinians.

Transportation fees surged from three Egyptian pounds (about $0.50) to a whopping 10 Egyptian Pounds - a 150 percent increase in one day!

Taxi drivers were worried about traveling to Areesh. “There’re a lot of [Egyptian police] checkpoints on the road to Areesh and I’m afraid they’ll take away my driving license,” said one.

However, more money and a good local guide quickly dispersed that fear. A young man from Sheikh Zewayyed, Ibrahim Sawarka, offered us his assistance and knowledge of bypass roads around the checkpoints, in exchange for a free ride to Areesh. His offer was immediately accepted.

Throughout the trip to Areesh we were constantly being greeted by joyful locals, who flashed the V-sign for victory and chanted “Palestine, Palestine”. We flashed back at them, feeling like victorious Romans on their victory parade.

The moment we laid eyes on Areesh, we felt free, relieved and happy - we were in another country without the need for a visa or any kind of procedures on the borders. Some of us had no proof of identification at all.

However, the surprise was to find the streets of the downtown area packed with thousands of Gazans, overflowing from the shops, cafés and parks. The once quiet resort town had become a hyperactive trading hub.

Business owners in Areesh seemed happy but rather stunned; they were happy to receive their Palestinian brethren after long years of separation, but stunned that Palestinians were buying everything that they could get their hands on. It was a massive ‘shop till you drop’ spree.

In a matter of a few hours, Areesh had almost nothing left to sell, and prices had climbed to exaggerated heights. Hundreds of visitors walked for hours just to find a restaurant that still had food, and the exchange rate for the Israeli shekel (the currency used in Gaza Strip) weakened from 0.8 shekel to 1 shekel per Egyptian Pound.

Fish, an abundant commodity in Areesh, and which normally sold for 6 Egyptian pounds per kg, had more than quadrupled in price, and we still had to wait in line until more fish was brought in by the fishermen.

As we searched Areesh for a ride home later at night, we ran into a friend from Gaza. He had been a frequent traveler to Egypt because he used to study there, so seeing Areesh was not as thrilling for him.

“Why did you come then?” we wondered.

“I didn’t come here to buy food or conduct business,” he replied. “I think most Gazans here came to Areesh to break the psychological barrier of closures.”

Yasser Abu Moailek is a freelance journalist and translator living in Gaza Strip. He contributes news items and feature stories to several news agencies around the world and has worked with foreign media outlets and NGOs in the Gaza Strip. He can be contacted on yasser_moailek@yahoo.com