The Electronic Intifada 18 December 2003

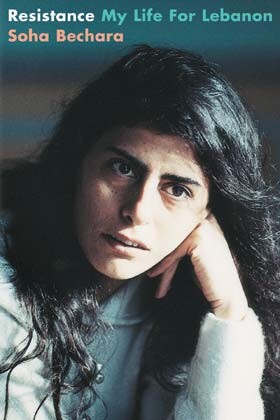

Resistance: My Life for Lebanon will soon be available from Soft Skull Press

Born to a family of secular Greek Orthodox Christians, she grew up during Lebanon’s fratricidal fighting. Béchara doesn’t describe it as religious fighting (Christian vs. Muslim), but as the left versus the right, and she skips over much of the details regarding the Christian minority’s struggle to keep the majority of political power from the demographically stronger Muslims. What she does emphasize is that as bad as the fighting during Lebanon’s civil wars was, it was nowhere near as horrible as what happened after Israel occupied Lebanon in 1978.

Bechara illustrates an idyllic childhood in the southern Lebanon village of Deir Mimas, only a few miles away from Khaim, the location of the prison whose inhospitality she would endure for ten years. Although the days leading up to her her birth date, June 15, 1967, were “day[s] of defeat for the Arab world,” the reality of Israel didn’t hit Deir Mimas until 1978. Villagers who worked in Israel “would rise at dawn, enduring meticulous searches and hours of humiliating delays at Israeli border stations, before reaching their workplace, where they would often be forced to labor at a punishing speed.”

Béchara adds, “in the early ’70s, my childhood years, no one in Deir Mimas would have imagined than less than a decade later invasion and then occupation were to be our fate.”

Not only does Béchara inherit her “father’s passion for politics” which she develops while staying with her uncle, but she also inherits his discretion. Knowing that her mother was averse to all politics being present in the house, Béchara quietly develops her contacts and becomes more involved in student political groups, not revealing much to her parents.

This skill would become vital to Béchara once she becomes more committed to the liberation of southern Lebanon as she enters into her late teens. Evading varying security forces, which were often more corrupt than committed to any single party or ideology, Béchara moves to and from occupied south Lebanon and Beirut while coming up with plots to demonstrate Lebanon’s resistance to Israeli occupation.

Béchara actively commits herself to the resistance at the age of 15. Organizing student protests, she notes that on one occasion, “I shouted slogans with so much energy that a man who saw me remarked to no one in particular: ‘That girl — she’ll end up a suicide bomber, that’s for sure!’” Her conviction was further solidified in January 1985, when Sanaa Mehaydle “became the first girl to commit a suicide attack in the occupied zone, voluntarily detonating the bomb she carried in the middle of an Israeli patrol.”

It is worth noting that Béchara sought out involvement in the Lebanese Resistance Front. She did not become brainwashed, and did not commit herself to any particular ideology. Her sole objective was to get Israel out of Lebanon. Although she was committed to the Lebanese Resistance Front, Béchara does not go into detail regarding its particulars. She writes, “Ever since the announcement, on September 16, 1982, of the creation of a united Lebanese Resistance Front against the Israeli occupation, my mind was made up. I was going to join them.”

Béchara has so much conviction for this cause that she turns down potential boyfriends so as to not compromise her commitment to the resistance, and even attempts an “exercise in seduction” on an unsuspecting friend, to see if she “was able to go that far” with an Israeli. She reinvents herself as a carefree, naive teenager who is not so interested in politics in order to prevent arousing suspicion. Eventually, she gains the trust of Minerva Lahad, Antoine’s isolated wife, by becoming her aerobics instructor. This provides Béchara with the opportunity to assassinate the Israeli-supported general in his own home.

However, Béchara doesn’t fit the preconceived notions of a militant who would be willing to die for Lebanon (it is not so explicitly stated, but rather implied that she would have become a suicide bomber if the resistance called for it). She is smart, successful in school, comes from a good family, and, of course, is female.

And Béchara the narrator does not explore in depth her attitude regarding legitimate violence. She refuses to kidnap Lahad’s young boy, and consciously chooses to shoot Lahad in the chest rather than the head (although she probably would have successfully killed him if she had) in attempt to make the scene less gory. But there is not a satisfying exploration of Béchara’s internal struggle regarding violent resistance — the reader just has a chronology of Béchara’s life.

It isn’t until the latter part of the book, when Béchara is in prison, that her psychology is more fully revealed. After her somewhat anticlimactic assassination attempt, Béchara realizes that she has no exit strategy, and is immediately arrested. She is beaten, tortured, threatened with rape, and her family members are all rounded up as well.

Refusing to give her interrogators the information they want, Béchara quickly becomes branded as a difficult inmate. The prison director, Abu Nabil, makes Béchara’s life as difficult as possible. She explains how she maintained sanity during solitary confinement, and how she committed herself to exercise every day, even when her wrist was handcuffed to her ankle. Béchara understands the importance of keeping her mental health, and despite the constant torture, writes poetry and stealthily steals materials out of garbage cans in order to make a deck of playing cards and even a chess board. She also uses this opportunity to learn passages from the Koran from her fellow inmates.

The narration of Béchara’s psychological struggles while she is in prison is the most effective opportunity the audience given to bond with their narrator. The stark, generally unflowered language used to tell the story (it is revealed in the prologue that Béchara wrote poetry, and its a disappointment when the reader finds none), makes it difficult to fully empathize with Béchara. This may be a problem with translation — it is likely Béchara’s story in her own language would be a richer one. And although the story is compelling, and its 175 pages go by fast, it is missing that extra layer of narration that would let readers in on the true mental process of someone who is ready to give their life for their country.

Maureen Clare Murphy is an Arts Correspondent for both EI and eIraq.