The Electronic Intifada 7 August 2012

Not the Israel my Parents Promised Me is the story of one of the quietest of human dramas: the act of changing one’s mind.

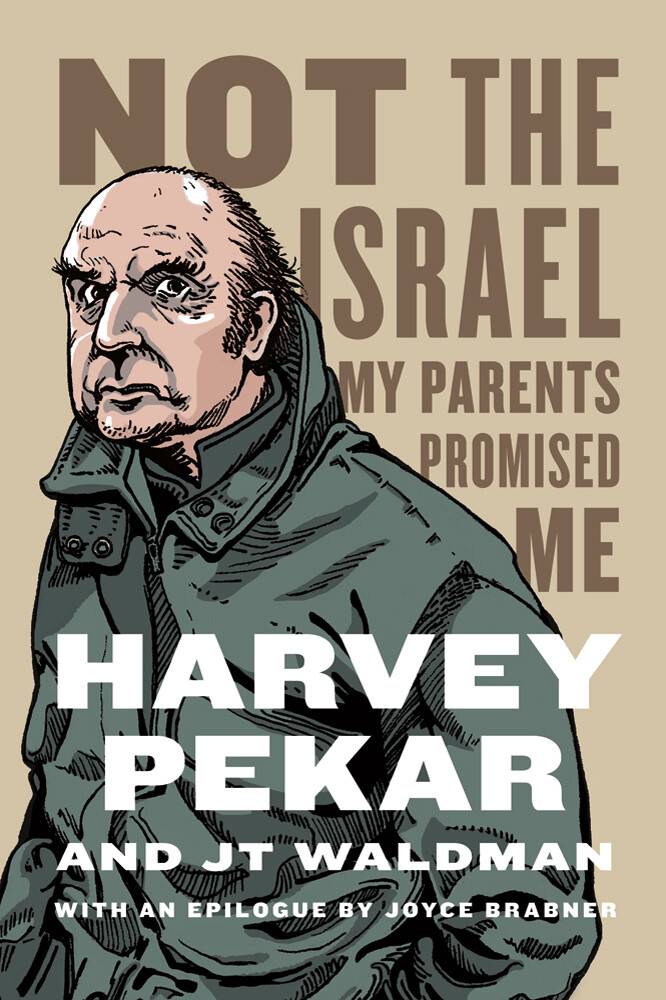

In this graphic novel, legendary comic book writer Harvey Pekar and illustrator JT Waldman examine Pekar’s disillusionment with the State of Israel. Pekar and Waldman weave together Jewish history with Pekar’s memories from his childhood experiences as the son of ardent Zionists. Published two years after his death, the book captures Pekar’s talent for unabashed truth-telling.

It is hard to imagine a better narrator for this graphic novel than the critically-acclaimed curmudgeon of comics, Harvey Pekar. Through his series of autobiographical comics titled American Splendor, Pekar defined the graphic memoir genre.

In Not the Israel my Parents Promised Me, Pekar speaks with the brutal honesty that characterizes all of his work. This is not a comprehensive examination of Israel’s occupation of Palestine, but it is a compelling and persuasive argument against nationalism and for justice.

Pekar writes, “I guess the story begins with my parents. I have them to thank for my personal entanglement with Israel” (8). Pekar’s father believed Israel to be the fulfillment of religious prophesy. His non-religious mother believed Israel would fulfill the promise of communism. But both of Pekar’s parents believed wholeheartedly in the Jewish state.

Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me is told as a conversation between Pekar and Waldman as they drive through Cleveland, Ohio — Pekar’s hometown. Waldman and Pekar discuss history, contemporary politics, Pekar’s memories and his conclusions about Zionism, nationalism and Israel. Pekar explains, “For centuries Jews endured horrible suffering and like other people deserve the right to self-determination, but the current trajectory of Israel frightens me” (86).

For readers who want to understand a Jewish anti-Zionist perspective, this book will not disappoint. Likewise, Pekar will satisfy readers who want to understand the historical context of Zionism. Pekar begins with Abraham and follows Jewish history though the crusades, the Holocaust, Jewish emigration to Palestine, Israel’s foundation in 1948 and occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967, and into the present day. Waldman’s expressive illustrations add emotional depth to Pekar’s story. Waldman’s style is both engaging and clear, making this a graphic novel that is accessible for readers less familiar with comics.

Selective at times

Pekar does not attempt to represent a Palestinian perspective. Though he supplies an accurate overview of Jewish history, students of Palestinian history will find his portrayal occasionally lacking. Pekar uses the Arabic word Nakba (catastrophe), to describe the 1948 war between Arab states and newly-established Israeli state. Pekar, however, does not mention what Palestinians generally use the word Nakba to describe: the violent displacement of more than 750,000 Palestinians and the creation of a refugee crisis that lasts to this day. Pekar, however, doesn’t balk from recounting the massacre at Deir Yassin or from calling armed Zionist groups like the Stern gang and the Irgun “Jewish terrorists.”

This book will persuade many readers to begin reconsidering support for Israel, but it can certainly only be a start to a conversation that must include the voices of Palestinians.

It is tempting to criticize Pekar for what he does not include. But this book is masterfully persuasive, in part because it is simple, honest and free of all pretensions. As always, Pekar speaks only for himself. He promotes no political prescriptions. “What do I know? I make comic books,” he says. “I do know the difference between right and wrong, though” (156).

Subtle but powerful

Whatever else we might wish him to include, Pekar manages to challenge nationalism in a subtle, but powerful way. Pekar and Waldman’s conversation creates a compelling picture of a man who Pekar’s wife rightfully describes as “proudly Jewish but not nationalist” (172). Pekar would hate me for saying it, but his human decency and his refusal of ethnic exceptionalism are examples from which we would do well to learn.

Not the Israel my Parents Promised Me belongs in the growing body of Jewish anti-Zionist literature and is among the best of the recent well-spring of graphic novels about Palestine. Pekar explains his disillusionment with Israel and answers many questions that readers unfamiliar with the topic will ask. But Pekar’s account doesn’t try to be anything it isn’t.

Pekar writes, “I hope this book will change some minds but I dunno” (4).

Not the Israel my Parents Promised Me invites readers into a conversation about Israel and challenges us to hold all people accountable to basic values of justice. This poignant graphic novel is a fitting final statement from one of the most uncompromising voices in comics.

Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me will undoubtedly ignite controversy. I can think of no better memorial for Harvey Pekar.

Joy Ellison is a writer, activist, and comic book lover who spent three years in al-Tuwani, a small village in the South Hebron Hills which is resisting the expansion of Israeli settlements and the accompanying violence. Ellison is in the process of completing a graphic novel about al-Tuwani and can be followed on Twitter (@j_in_tuwani) and on Facebook.

Comments

I've read the book, and

Permalink Mark replied on

I've read the book, and concur.