Today we visited Bethlehem and the village east of the city, Beit Sahour. With a well-known history of resistance — non-violent civil disobedience and the tax resistance in 1988 — Beit Sahour has a reputation of active engagement in the struggle for freedom and justice. Bethlehem and the surrounding towns of Beit Jala and Beit Sahour are the backbone of the Palestinian Christian community, estimated at 180,000 people.

As expected, we had to get out of the taxi when we arrived at the checkpoint between Jerusalem and Bethlehem. As we walked, passing Israeli soldiers who have been imposing the siege on Bethlehem and surrounding villages, they called us back. We had to stand in line, showing the soldier our passports. One man carrying a Jerusalem-identity card — these work very like the “passbooks” of Apartheid South Africa — was not allowed in. We continued our way, took another taxi and went to visit George, a friend.

The Al-Khader protests

At his family home we met an Israeli peace activist, Neta Golan. Her arm was broken by Israeli police at a demonstration, Friday afternoon, as she was forcibly removed from an area near the village of al-Khader. Last week settlers set up new caravans on land belonging to Palestinians in Al-Khader, south of Bethlehem. Many villagers from al-Khader rely entirely on agriculture as their source of income and this fact has made them the group that is most vulnerable to Israeli colonial aggression. Because the lands of Al-Khader lie in close proximity to Israeli settlements, the villagers who own the land suffer frequent attacks from settlers as well as by the Israeli occupation forces.

Yesterday, Palestinians, Israelis and internationals living in the country demonstrated near al-Khader to protest against the latest move by the settlers. At one point, the Israeli occupation forces declared the area a “closed military zone” and protesters were given six minutes to leave the place. As she was walking away, an Israeli police officer twisted Neta’s arm until it broke. She was not allowed to receive medical attention.

“After several hours,” she told us, “I was pushed out of the police station and was forced to make my own way to hospital with a broken hand.” Neta was detained along with five other Israeli activists. Since there was no international media presence, the Israeli soldiers and police were allowed to act in a cruel and brutal way. Later we met other Palestinian participants of the Friday-demonstration who showed the bruises sustained from blows. More than six other Palestinians were injured in al-Khader.

Shedma

The homes of Joseph Hijazin and Karem Sar’awi (AEF, 2001)

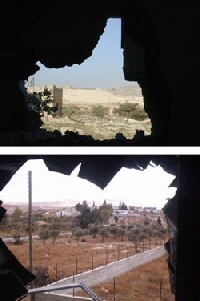

Shedma military base, as seen through damaged walls (AEF, 2001)

Since the Intifada erupted on 29 September 2000, Israeli shells and heavy gunfire have completely destroyed a total of 3,669 residential buildings. In the past few months alone, more than 200 residential homes have been damaged to various degrees. Four were completely destroyed and eight need to be rebuilt completely. Churches, mosques, and refugee camps have also been attacked.

Later in Bethlehem, we passed by the Church of Nativity and saw an empty Manger Square. The tightened siege and the months of closure have been catastrophic for Bethlehem’s tourism-dependent economy. Restaurants and hotels remain empty. A man who was sells falafal, the best in the area, told us about the economic deprivation and looked as he was almost getting used to this situation.

This is still something that amazes me every single day, the way Palestinians continually adjust themselves to the situation. It does not mean accepting their circumstances but trying to continue to live in the midst of them and to remain on their land. It is even more amazing when you realise that the economic deprivation that people here have to deal with is happening in the middle of Israeli bombardments and shelling.

Dheisheh

We drove south and visited Dheisheh, one of the refugee camps in the Bethlehem district. This refugee camp was created in 1949 on 430 dunums. Today the camp shelters more than 11,000 refugees and still covers only 430 dunums, a ridiculously small amount of space. Dheishe’s residents were particularly active during the first Intifada. The Israeli occupation forces built a fence around the camp and a metal turnstile for the main entrance, which were in place for almost eight years.

The remains of the iron entrance is still there. Last year, in August 2000, when I was in Dheisheh, I visited the Ibdaa Cultural Center, which means “creating something from nothing” in Arabic.

I spent the whole day with Ziad Abbas one of Ibdaa’s directors. That day I also met another contact,Muna, for the first time, after only having known each other by email for a couple of years.

I was hoping to meet Ziad today but he was in Sweden but visited Ibdaa’s new building. Last year, Ziad had shown me around while they were still busy with furnishing. Now I could see how these plans had developed. We spent some time looking at black and white pictures of various Palestinian villages from before 1948 and of the plight of the refugees.

For the children in Dheisheh, Ibdaa is a source of learning and empowerment. Its dance troupe is known internationally for dances that capture the Palestinian refugee experience. Its oral history project takes young people to visit the nearby demolished villages of their parents and grandparents. Its website enables refugee youth across the region to bridge the physical barriers between them, to communicate, and to renew the pledge to leave the refugee camps and return home one day. After my visit last year, my memory of the faces of Dheisheh’s children really energized and motivated me.

After I returned to Holland, I heard the news of the fire. In the pre-dawn hours of 26 August 2000, someone scaled the two-story walls of the cultural center, stole the computer server, and set fire to the center. Today, in the gutted youth center, nothing remains but 14 charred computers, equipment that the children used to connect to other young refugees in Shatila refugee camp in Lebanon and elsewhere. The Across Borders project had been the first Internet project set up by and for refugee children.

Today, Annet, who has worked and lived in Namibia for a while, pointed at a picture of Dheisheh refugee camp and the shelters built by UNRWA in the mid-1950s to replace the original tents that housed the refugees after the 1948 war. “It’s like the homes in the townships in Namibia”, she said. We went to the roof of the building and sat there for a while, looking out thoughtfully at the camp.

In the evening I was reminded by the words of Tawfiq Ziyad:

“Here we shall stay, sing our songs, take to the angry streets, fill prisons with dignity.”

Having dinner with friends, listening to songs about the land and people, and discussing politics and ways forward, as the siege continues.