Arab Association for Human Rights (HRA) 15 June 2006

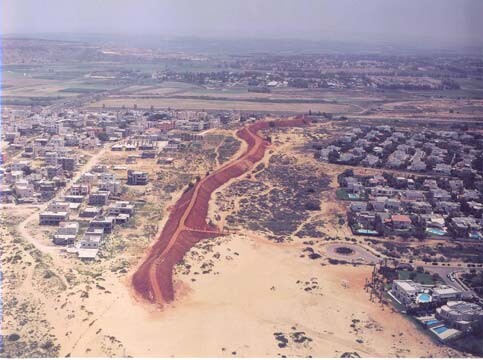

Earth embankment between Jisr Al-Zarqa and Qisariya (HRA)

Background

The Palestinian Arab minority and the Jewish majority in the State of Israel live largely in separate areas. With the exception of the mixed cities, in which a significant Palestinian minority lives alongside a clear Jewish majority, most of the Palestinian population lives in its own communities, as does the Jewish majority. This territorial separation is also seen within the mixed cities: most of the Palestinian minority lives in its own neighborhoods, which are distinct from the neighborhoods inhabited by the Jewish majority.

This separation is the result of historical developments before and after the establishment of the State of Israel. Today, however, it may be considered to originate from the manner of allocation of land owned or controlled by the state, which comprise 93 percent of all land in Israel. The manner of allocation of this land is the result of pro-active planning decisions by the authorities. In state-owned or controlled land, the state acts deliberately to create such territorial separation, allocating separate land for development and construction for the two populations.

An important question that arises in the context of the issue of the residential separation between the Jewish majority and the Palestinian minority, as in other fields such as education, is whether separation is contrary to the principle of equality. In the past, the prevailing view was that such separation per se was not discriminatory, based on the principle of “separate but equal.” However, since the ruling in the United States in Brown v Board of Education of Topeka, which established that the policy of separation between whites and blacks in education was “inherently unequal,” thinking on this matter has changed. This ruling has provided the foundation for a far-reaching revision of the attitude to separation between different groups within society, both in the United States and throughout the world. This approach is based on the perception that separation implies disrespect toward the excluded minority group, emphasizes differences between it and others, and perpetuates feelings of social inferiority.

The 3 Separation Walls

In Israel, however, apart from the territorial separation between the Jewish majority and the Palestinian minority, and the question as to whether such separation infringes the principle of equality, recent years have seen the establishment of separation walls and fences between Arab and Jewish communities within the State of Israel, and, in other cases, between Arab and Jewish neighborhoods within the same city. This physical separation has been initiated by the Jewish majority and the Israeli establishment. The purpose of these walls and fences is to separate the Jewish majority and the Palestinian minority, and to prevent physical or even eye contact between the two populations.

1) The Earth Embankment between Jisr Al-Zarqa and Qisariya - 1-1.5 kilometers long and 4-5 meters high

Jisr Al-Zarqa is an Arab village on the Mediterranean coast in the northern Sharon region. For many years, the village has suffered from severe overcrowding and a lack of space for access roads and residential and public needs. Neglect by the various authorities has led to rising crime rates and drug problems.

Qisariya is an ancient port on the northern Sharon coast. In 1948, it was one of the first towns where the Hagana undertook planned expulsions and the destruction of homes. Today, the population of the town is entirely Jewish. The population is of high socioeconomic status, and includes many very wealthy residents.

In November 2002, the residents of Jisr Al-Zarqa were surprised to discover that work had begun to construct a strip-shaped earth embankment designed to separate the two communities. The establishment of the embankment was undertaken and financed by the Qisariya Development Company, without any lawful permit, without any coordination with the Jisr Al-Zarqa local council and without informing the residents.

The Qisariya Development Company referred to the embankment as an “acoustic embankment.” They claimed that it was established in order to alleviate the acoustic “hazards” faced by the residents of Qisariya due to noise caused by the residents of Jisr Al-Zarqa (the prayer calls of the muezzin, loud music, parties, shooting in the air during celebrations, and fireworks). It was also alleged that the embankment would protect the residents of Qisariya against the “scourge” of thefts they faced as residents of Jisr Al-Zarqa “infiltrated” Qisariya and stole objects from the yards of the local houses. It was also claimed that the proximity of the northern neighborhoods of Qisariya to the Arab village had led to falling property prices in this area.

The residents of Jisr Al-Zarqa refer to the embankment as a “racist barrier.” They feel that its purpose is to choke them and encourage them to move elsewhere. A national park borders the village to the north, the embankment to the south, the main highway to the east and the sea to the west. The village now has no possibility to develop.

The embankment certainly constitutes a serious obstacle to the urban planning of the village, preventing the possibility of building a by-pass road as planned in the past. It also severely impairs a beautiful landscape, blocking views of the sea and of nature and causing distress and frustration to the residents of the southern neighborhood of the village.

2) The Wall between the Jawarish Neighborhood and the Gannei Dan Neighborhood in Ramle - 4 meters high and approximately 2 kilometers long

Wall between Jawarish neighborhood and Gannei Dan neighborhood in Ramle (HRA)

Ramle is a city on the inner coastal plain in the Central District of Israel, close to the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem highway. In 1948, Ramle became a mixed city when it was occupied by Israeli military forces, who expelled the majority of its Arab population. As of September 2003, the city had a population of 63,000, 80.5 percent of whom were Jews and 19.5 percent Arabs.

In 1950, several Arab families from the small town of Majdal were brought to an area adjacent to Ramle, where the State of Israel established the village of Jawarish. In 1965, Jawarish was annexed to Ramle. The neighborhood now has a population of some 2,000 Arabs. The average monthly income of the residents of Jawarish is significantly below the national average; most of the residents work in the construction industry and in agriculture.

In the mid-1990s, during the period of mass immigration from the former Soviet Union, the Gannei Dan neighborhood was built close to Jawarish. This neighborhood has a population of approximately 2,000, including approximately 80 Arabs. Gannei Dan enjoys a good socioeconomic level.

One of the main characteristics of the spatial profile of the Ramle area is the physical separation between the Jewish neighborhood of Gannei Dan and the Arab neighborhood of Jawarish. During the construction of Gannei Dan, and as an integral part of the planning, a concrete wall was built, 4 meters high and approximately 2 kilometers long, separating the new neighborhood from Jawarish, and blocking both physical and eye contact. This wall was built and financed by the promoters who developed the Gannei Dan neighborhood.

Most of the residents of the Arab neighborhood were opposed to the separation and to the construction of this wall, given its length and height. The opposition focused mainly on the insult they felt faced with the hostile attitude of their Jewish neighbors, which they felt regarded them as inferior people, as well as the fact that the construction of the wall was imposed on them by their Jewish neighbors and the Israeli establishment.

The residents of the Jewish neighborhoods largely supported the establishment of the separation wall. They felt that separation was a simple and logical feature of the area. Some also claimed that Jewish residents would not move to the neighborhood unless the wall was constructed. This support reflected their claims that they “suffered” from the proximity to the Arab neighborhoods: the general inconvenience of living near Arabs, fear of criminals and drug addicts, concerns relating to the feud between two families in Jawarish involved in drug dealing (a feud that has cost 32 lives), and falling real estate prices due to the proximity to the Arab neighborhoods.

3) The Wall between the Neighborhood of Pardes Snir in Lid and Moshav Nir Zvi - 4-meter high wall of concrete and bricks be built along a length of approximately 1.5 kilometers

Wall between the neighborhood of Pardes Snir in Lid and Moshav Nir Zvi (HRA)

The city of Lid is situated on the eastern edge of the coastal plain, close to the city of Ramle. In 1948, Lid became a mixed city. As of 2003, the city has a population of 74,000, of whom 72.5 percent are Jews and the rest Arabs. Most of the Arab population lives in poor neighborhoods that suffer from a lack of proper urban planning, poor sanitary conditions, and from high levels of crime and drug dealing.

Pardes Snir is an Arab neighborhood on the western edge of Lid, with a population of approximately 3,000 (as of 2003). It has a reputation as a disadvantaged neighborhood that suffers from problems in almost all spheres of life due to longstanding neglect. Among other problems, the neighborhood suffers from the absence of any plan regulating construction in order to meet the minimum and most basic needs of the population. As a result, and due to the growing needs of the population, most of the construction in the neighborhood is unregulated, and Pardes Snir is developing organically without any planning and without the appropriate infrastructure.

Nir Zvi is a moshav (a cooperative Jewish agricultural community) adjacent to the neighborhood of Pardes Snir. It has a reputation as a prestigious, prosperous and well-maintained community whose Jewish residents come from the middle and upper classes.

On July 21, 2002, Government Decision No. 2264 was adopted. The explanatory comments to the decision, which relates to the rehabilitation of the city of Lid, state that it aims to address the problems faced by weak populations, including the Arab population of the city. However, the decision also included the following measure:

“The Ministry of Transport and the Ministry of Housing and Construction will be charged with erecting an acoustic wall between the Pardes Snir neighborhood and Moshav Nir Zvi, and with presenting the Director-General of the Prime Minister’s Office within 14 days with a work plan for the establishment of the said project.”

On June 13, 2003, Local Outline Plan No. GD/475/24 was submitted for approval. One of the goals of this plan was to establish provisions for the construction of a wall alongside the road between the neighborhood of Pardes Snir and the moshav of Nir Zvi. The plan proposed a wall be erected along the road’s edge and with a height of 4 meters.

On July 23, 2003, Ludim Local Building and Planning Committee issued a building permit permitting the establishment of a wall between the neighborhood and the moshav. Construction of the wall duly began, but the work was halted in accordance with a temporary injunction issued by the court following an administrative appeal filed by several residents of the neighborhood. As of today, approximately one-third of the wall has been constructed.

The residents of Moshav Nir Zvi claim that this is an “acoustic wall.” They also claim that they suffer from burglaries in their homes by drug addicts who come to Pardes Nir neighborhood to buy drugs, as well as from agricultural losses. A further claim is that apartment prices have dropped by approximately 40 percent due to the proximity to the Arab neighborhood. Accordingly, the wall is “needed” in order to “protect” them.

A professional opinion prepared by Bimkom – Planners for Planning Rights regarding this separation wall suggests that there were planning defects in the establishment of the wall. The opinion shows that, in this case, there is a gross lack of balance between the benefit accruing from the establishment of the wall for one population (the residents of Nir Zvi) and the damage to another, weaker population group (the residents of the Pardes Snir neighborhood). In addition, the decision to establish the wall met the needs of one population while ignoring those of the other. The opinion further shows that the wall will impair the urban quality of life of the residents of Pardes Snir, severely eroding their access and their right to freedom of movement and open space. The wall will transform a local neighborhood road forming an integral part of a living and dynamic urban fabric, without any clear limit of right, into a space of geographical, ethnic, racial, social and economic separation. The proximity and height of the wall severely injure the residents of the neighborhood, particularly those who live close to the road. It blocks breeze from the west, obscures the open view and hence constitutes a grave esthetic hazard.

Discussion

In the three locations where walls have been established, the Jewish residents claim that the intention is to prevent noise hazards allegedly caused by the Arab residents. However, the circumstances in which the walls were established suggest that the use of the term “acoustic wall” is intended to disguise the true nature and purpose of these separations. The length and height of the walls clearly suggests that their true purpose is not “acoustic” separation, but total separation between the two populations, preventing all contact, both physical and visual.

The decision by the government to finance the separation wall in Lid suggests that the establishment of walls and fences is not a response to local problems of noise and thefts, as the Jewish residents have attempted to suggest, but rather an important national issue relating to the preservation of the Jewish character of the state, in general, and the severing of contacts with the Palestinian minority, in particular.

The separation walls also reflect the perception of the Palestinian minority by the Jewish majority as a “demographic threat.” Once the Palestinian minority has been defined as a “threat” to the Jewish and Zionist character of the state, the Jewish majority should separate itself from the Palestinians and prevent any contact with the minority population.

In fact, the establishment of walls and fences forms part of a broader trend toward racial separation between the two populations, including the ghettoization of the Palestinian minority. These processes of racial separation and ghettoization are manifested in physical terms both in the territorial separation between the two populations and in the constructions of high walls and fences preventing the natural urban development of the Arab communities. This is compounded by the difficulties faced by Arab residents who attempt to seek more suitable housing opportunities in Jewish communities – difficulties that are the product of racist motives. The net result is a depressing reality of Arab ghettoes surrounded by Jewish communities, and, in some cases, by separation walls and fences.

To date, only three locations have been documented where separation walls have been established. In this respect, it would be inaccurate to depict the separation walls as a common phenomenon in Israeli society. However, the Arab Association for Human Rights (HRA) believes that these walls may serve as a dangerous precedent for the establishment of additional walls and fences in the future. Suggestions have already been heard that a further high separation wall should be established between Pardes Snir neighborhood in Lid and the adjacent Jewish neighborhood of Gannei Aviv. In addition, and against the background of the separation barrier that has largely been completed within the Occupied Territories, the idea of the separation of the two populations – Jews and Palestinians, both in the Occupied Territories and inside Israel – seems to have become more popular among the Jewish majority. Accordingly, there is room for concern that in the future, elements within Israel will advocate the establishment of further fences and walls in various locations, thus exacerbating the trend to racial separation and ghettoization.

International human rights law regards racial separation as a gross violation of human rights. Thus, for example, the 9th and 10th paragraphs in the preamble to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination 1965, note that the signatory countries are:

“Convinced that the existence of racial barriers is repugnant to the ideals of any human society,

Alarmed by manifestations of racial discrimination still in evidence in some areas of the world and by governmental policies based on racial superiority or hatred, such as policies of apartheid, segregation or separation…”

The establishment of walls and fences gravely impairs the right to equality and human dignity of the Palestinian minority, which is the weakest population group in Israel in political, economic and social terms, both because of the walls’ coercive manner of establishment and their inherent nature. By establishing such walls, the Jewish majority sends a clear message to the Palestinian minority that they are not welcome citizens and that there is no possibility for the two populations to live together. The walls and fences also severely and brutally prevent possibilities for future expansion and development of the Arab communities, since they constitute an irreversible physical obstacle to the different development of the area in the future, thus violating the right to planning and to open space.

The HRA’s urgent call to action

The HRA believes that the establishment of the separation walls and fences is an unacceptable and improper policy that carries grave consequences for relations between the Jewish majority and the Palestinian minority. The HRA believes that the establishment of these walls gravely violates the basic human rights of the Palestinian minority to equality and human dignity, and constitutes a violation of international law.

In accordance with international law, every state is obliged to act effectively to prevent the racial separation of different populations. However, the State of Israel is not only failing to prevent the establishment of such walls and fences, but is actually encouraging and assisting in these actions. Accordingly, the HRA urges the State of Israel to cease this violation of international law, to act immediately to demolish all the walls and fences already established, and to prevent the establishment of additional walls and fences in the future.

The HRA also calls on the international community committed to peace and human rights to take all possible and necessary steps to halt the growing legitimization of the phenomenon of racial separation in Israel. The HRA warns that this phenomenon is potentially explosive and could jeopardize any chance for proper relations and a normal joint life for both populations, particularly in the case of a national minority that will continue to exist and live within the state.

The Arab Association for Human Rights was founded in 1988 to promote and protect the political, civil, economic, and cultural rights of the Palestinian Arab minority in Israel and to further the domestic implementation of international human rights principles. It is an independent non-governmental organisation registered in Israel. HRA holds a unique position locally and worldwide as an indigenous organization that works on the community, national and international levels for equality and non-discrimination, and for the domestic implementation of international minority rights protections.The full version of this report is available at http://www.arabhra.org/publications/reports

/Word/SeperationWallsReport_English.doc.