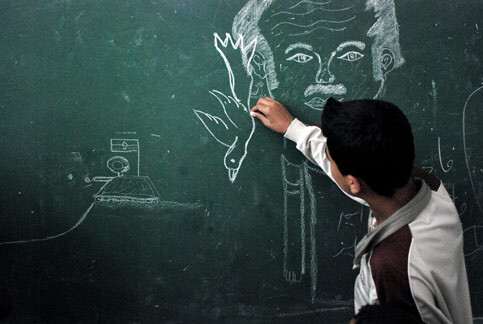

Baddawi Refugee Camp 2 June 2007

One of Nahr al-Bared’s displaced at an UNRWA school in Baddawi Refugee Camp. (Tanya Traboulsi)

1 June 2007

I have been to the Baddawi camp twice now. It is swarming with people and has more than doubled in population. The future of the camp is bleak and according to the World Health Organization the likelihood of disease is high, and there is limited water and electricity. The number of civilian deaths in the Nahr al-Bared camp is difficult to determine due to a media blackout; my last check saw a range between 17 and 40, but today’s indiscriminate bombing from land and sea has certainly increased this figure. In the Lebanese daily An-Nahar, on 31 May, there was a single story that only reported the details of the deaths of Lebanese soldiers. The official number from the Lebanese army over last weekend was a resounding one civilian death.

By denying Palestinian civilian deaths we effectively commit a double crime: The first is the indiscriminate death of the victim; the second is the denial of this original crime. I suppose the victim is meant to carry a camera and document her own death to truly confirm it in the public’s eyes.

I felt this as I stood in front of two Palestine Red Crescent Society volunteers in the Baddawi camp while they argued about the number of victims and how the army was making it difficult to document the deaths and the situation in the camp. I stood as they tried to prove to me, hoping I would get the word out, that there was more than one death. It mattered so much to them; it mattered more than the world that there was more than one death. In my mind I caught a glimpse of the idealist romantic in me and thought of how the world should react to even one death; that it was not in the numbers, it was in the act itself. But I caught myself and came back to the ways of this world: the numbers do matter; the proof of dead bodies is required, and the media needs pictures, names, time and cause of death before it will believe the story of the victim over that of the state. As it stands, the Palestinian is killed and then denied the recognition of her unjust death. With no recognition of injustice how can people deal with their loss?

And it is not the first injustice denied to these people. It begins with the denial of their right to return to Palestine. Standing in an overcrowded Baddawi camp, I found myself making conversation by asking one man a question about his origins; a painful question for a Palestinian refugee.

To be Palestinian in Lebanon is to be wished a thousand deaths and hunted a million times.

And the man’s reply was that his family was originally from a village outside of Haifa. His grandfather fled to Tel al-Zaatar; any Lebanese can tell you about the massacre there in 1976. After which they fled to Chatilla; any Lebanese can tell you about the massacre there in 1982. And so after that they fled to Nahr al-Bared; few Lebanese will tell you what is happening there now or call it a massacre. He is now in the Baddawi camp hoping to return, but if the curse of Palestinian return is any indication, it might be decades before this man, Nasser, returns to anywhere but the UNRWA school he resides in now. And that is probably the real reason why there are still about 10,000 people in Nahr al-Bared who refuse to leave what they now call their homes. They already have experience from the last time they left.

Mona, a woman from the Nahr al-Bared camp, reinforces this idea. She speaks to me passionately: “I care deeply about the camp. It is the symbol of my refuge; it is the place from where I will defend my cause and from where I struggle for my right to return to Palestine.” She continued: “If they remove all civilians from Nahr al-Bared the army will completely demolish the camp. I need to defend the camp. In a few days we will all return if there is no solution. People want the civilians out but we will return. We are thinking of this option now if things stay as they are.”

She reminds me of the Lebanese in the war this summer speaking in relation to the South: how they wanted to return and how the men did not want to leave. People here value home as an extension of their lives and their bodies. They want to remain because escaping into the uncertain world is an infringement on their humanity and perhaps equal, at that moment of departure, to the finality of death. For some reason the Lebanese expect the Palestinians to just desert their homes as if they were meaningless when they themselves would not and have a history of staying their ground.

At the camp, one of the guys there tells me that in recent years there has been more intermixing between Palestinians and Lebanese, and that this was new. He said this with enthusiasm to show a common ground between us, and that he thought better times were ahead. I suppose the idea is that marriage brings two tribes together, so why not two nations. It doesn’t seem to work that way though. No matter how many mixed national marriages there are between the Lebanese and Palestinians or Lebanese and Syrians, the people still fight. Kinship and nation-state politics don’t really work in the same way as kinship does with tribal politics. Somehow the relationships don’t have meaning in state diplomacy, and it is perhaps because of the firm detachment between the family and the state. So we can intermarry from here till next century but to no avail. The state will adamantly privilege the general population over the family and the general population will remain “purely Lebanese” — whatever that means.

The Lebanese army is committing crimes in the Nahr al-Bared camp and the Lebanese are silent. Perhaps the Lebanese should imagine the camp was a Beirut neighborhood and Fatah al-Islam was hiding, lets say, in Ashrafieh or the Hamra area. They should then ask themselves if they would be calling on the army to use the same methods to get rid of the group.

Agreed, terrorists should not hide behind civilians, but when they do, state armies also have a responsibility to not destroy the civilian population. Remember, the civilians are victims and now the army is killing the victim. The Palestinians of Nahr al-Bared are hostages. The army is killing the hostage and destroying his town and home. Is there logic to this?

The Palestinians cannot be punished for their leadership’s incompetence. Otherwise, we should ask if the Lebanese people should be punished for their leadership’s incompetence. The Lebanese army can take a stand but it needs to do so within the rules of war. If it cannot, then it should not fight a battle it cannot win.

Here is where the Lebanese people and government are to fault. The people are to fault for their silence and the government for its unaccountable behavior, its inability to govern its own affairs and then blaming it on everyone else, and its direct or indirect complicity in the arming of Fatah al-Islam. Again, I call for a full investigation of the recent events and into the dealings of the top politicians (Opposition and March 14) in the country. With no accountability there will always be political space for militias to harvest.

Note: In the meantime, tonight we are beginning to hear that things in the Ein al-Hilweh camp in the South are starting to flare up. None of this is making sense; something is definitely not right!

Sami Hermez is a doctoral student of anthropology at Princeton University researching violence and armed resistance in Lebanon and has been active in relief and redevelopment projects in the south of Lebanon. Sami can be reached at shermez at princeton.edu.

Related Links