The Electronic Intifada 30 August 2010

Artists may trust to the innate power of their work to transcend its exploitation as propaganda. Or they may offer it precisely for such purposes (agit-prop). Or they may seek to withhold it by participation in a campaign of cultural boycott, a tactic being increasingly deployed against the Israeli state.

A seemingly exceptional situation arises when the political context from which art emerges is simultaneously the surface on which it is inscribed. The Berlin Wall has been described as “the world’s longest canvas” and was used as such by artists like Thierry Noir, Keith Haring and a host of unknowns.

However, this art appeared mostly on the Western side of the wall, and hence supposedly symbolized, in the words of a dedicated website, “the free expression of the open society of West Berlin” as opposed to “the blank walls of the repressed society that was East Berlin” (Berlin Wall Art).

Although the wall surrounded West Berlin, the citizens of that city were free to travel at will, unlike their East-Berlin counterparts. Hence, West Berlin wall art was viewed approvingly by the capitalist regime that would engulf the former German Democratic Republic once Germany was reunited, while those who sought to resist Stalinism from within were denied any such outlet.

Israel’s wall in the occupied West Bank, including in and around East Jerusalem, was declared illegal by the International Court of Justice in July 2004. Although it is often compared to the Berlin Wall, it differs in several essential aspects. The Israeli side — located within the so-called “free world” — is often decorated by officialdom with idyllic landscapes designed to conceal its “concrete” reality. On the Palestinian side, the interior walls of the prison that is the occupied West Bank, resistance art is now flourishing.

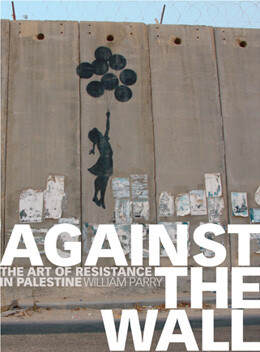

Unlike the East German authorities, the Israelis seem content to leave this art in place. This may be linked to the celebrity of some of the participating artists, in particular the Englishman Banksy whose “Girl with balloons” features on the cover of William Parry’s Against the Wall. Parry, a London-based journalist and photographer, documents “the art of resistance in Palestine.”

This beautifully produced book falls into a number of the traps concealed within the ambiguous art/politics relationship evoked above. However, it ultimately retains its value and impact as both a political and aesthetic document, perhaps exemplifying the German philosopher Walter Benjamin’s famous thesis that “[t]here is no document of culture that is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

One risk inherent in “political art” is that it may be seen to exploit oppression in the interests of an artist’s reputation and bank balance. Banksy’s 2007 “Santa’s Ghetto” project in Bethlehem, central to Against the Wall, sought to subvert these risks by forcing those wishing to view works by their favorite artists to travel to the occupied Palestinian territories and see for themselves the conditions under which Palestinians live.

However, if “the art of resistance” is thus equated with that of non-Palestinian celebrities, there is a risk that the agency of the Palestinians themselves is again being denied. Does such a project not itself symbolically enact the disempowerment it is supposedly opposing? The only Palestinian artist mentioned by name in this book is Suleiman Mansour (110) who apparently “participated in this project” (i.e., “Santa’s Ghetto”), but none of whose work is reproduced. The Palestinian artwork reproduced is invariably anonymous (147, 158-9).

Given the unsanctioned origins of street art and the guerilla-like tactics its creation often entails, it seems peculiarly adapted to a campaign for the destruction of the very surface on which it is created, in this case the apartheid wall. Further, such art invites and must tolerate the kind of defacement that is prohibited in the art gallery environment. Banksy’s “living room” scene has been “debeautified” with Arabic graffiti reading: “Park your car here for 3 NIS [New Israeli Shekels]” (29). His catapult-wielding rat was destroyed by locals who took offense at being compared (as they saw it) to a rodent (51), while his donkey undergoing a security check (110-111) was saved from a similar fate by the canny Palestinian owners of the building where it was painted, who removed the relevant section of wall and sold it to a Westerner.

Such cultural misunderstandings aside, the Palestinian response to this “outsider art” has been far from uncritical. The New York artist Swoon was “told by one of the elders from the refugee camp that they don’t necessarily want the kids to start viewing that area positively, and so they see the work as a thing of beauty, but in a place where beauty shouldn’t be.” Nonetheless, writes Parry, the people of Bethlehem “were effusive, ready to adopt Banksy as a son of the struggling city, given the number of tourists the project’s work has attracted” (10).

Parry’s text is impressively wide-ranging. His exposition of the historical and political realities of Palestinian life, particularly as it is bounded by the wall, is detailed, lucid and accurate. His photographs are themselves works of art, many of them focusing on Palestinian people and places rather than just on the artworks.

Yet the most striking photographs are those of artworks within their environment, such as the young Italian street artist Blu’s “giant baby, blowing soldiers made of money” on the wall near Aida refugee camp (64-65, and again, at dusk, 70-71). Indeed for me Blu, his compatriot Erica il Cane (“How the oppressed become the oppressor,” 68-9) and the Spaniard Sam3 (66-67, 68) stand out from the other named artists; their images seem to have more intrinsic subversive power than those of the more celebrated Banksy.

“Pardon our Oppression” is the title of a mural by the veteran Ron English (58-59), designed “to link American” — and European, he might have added — “support to the oppression of the Palestinian people.” Such a quasi-penitential acceptance of responsibility, common to much of the art reproduced here, extends the scope of “the art of resistance” to our Western societies and adds further depth to this tremendous and essential book.

Raymond Deane is a composer and Cultural Boycott Officer of the Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign (www.ipsc.ie).

Related Links