The Electronic Intifada 25 November 2005

“Beit Rishonim” (Founders’ House) in Herzliya is a museum that preserves and exhibits the history of the town that was founded as a pioneer settlement in 1924. The museum glorifies the founders who did not admit defeat despite the numerous hardships they faced. The museum holds mounted displays, spot-lit photographs and books that tell the story of the settlement that became a city. Some of the items also depict the pioneers’ Arab neighbors in the early days. These were residents of the villages Alharam (Sidna Ali), Ijlil, Abu Kishek and other Bedouin communities. I will try to interpret the museum’s position toward these local Arab residents through the pictures displayed in the museum, their captions, and some of the written texts.

This settlement in the heart of a solidly Arab area is put on display by the museum, and yet despite this (or perhaps because of it?) the museum emphasizes the “fact” that this area was desolate.

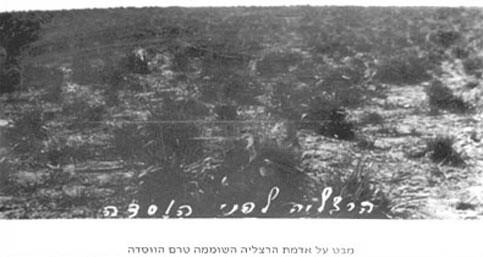

The above photograph shows “Herzliya before it was built” — these are the words written directly on the picture itself. The caption below the photograph reads: “View of desolate Herzliya before it was founded.” The narrative of “making the desert bloom” appears in this museum undisturbed side-by-side with the narrative of “settling in the heart of the Arab population.” The wasteland photo is somewhat blurry but does show some wild weeds growing. The composition chosen for this photo shows the virgin land waiting for Herzliya pioneers to come along and make it bloom. This “wasteland” is named “Herzliya” even before the town is founded. In other words, the land, nature itself, is named after the Hebrew town even before this name took real form. According to this narrative, the land waited for its Zionist settlers to build upon it and name it after the European man (Herzl) who dreamt it but never lived here. Or perhaps “Herzliya” had been the place name since the dawn of time? The settlers did not have to invent the name, it seems, only to rediscover and revive it.

In a fitting sequel to this description, another photo shows goats roaming the desolate landscape, with the caption “1930s landscape, goats in the dunes of Zone B before the beginning of settlement.” The goats, we know, are owned by neighboring Arabs, but they are absent from the caption. The goats roaming without a shepherd enhance the desolate feeling of the image. Another, more detailed, caption in the central hall of the museum offers the following explanation:

In 1936, when the first settlers arrived to Zones A and B (Herzliya Pituach of today), there were only bare sand dunes, prickly pear bushes, fig trees and occasional small vineyards that belonged to the Arab village Sidna Ali situated to the northwest. The land in that area was known as Alharam. The sandstone hills of Zone C were sparsely populated. The drive to Tel Aviv took about an hour and a half.

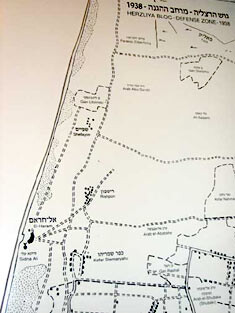

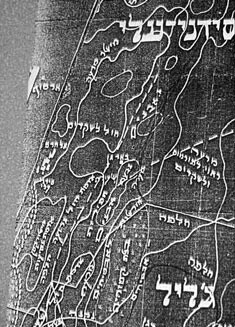

Arab culture, as described in the museum, is marginal in view of real civilization; the actual geographical reference point — Tel Aviv — is an hour and a half’s drive away. The “wasteland” in which Herzliya was built was, therefore, populated all around with Bedouins and Arab villages, but these do not become a subject on the museum walls. They are a thin and marginal background that belongs to the landscape waiting to be revived. The indigenous people are a part of this land that must be conquered and redeemed. This is illustrated clearly by another map that depicts agricultural plans for various plots of land in the area, as the settlers saw them.

Particular crops were assigned to each zone — watermelons, lupine, almonds, etc. On the map they are surrounded by the names Alharam, Sidni [sic] Ali, and Ijlil, as though these, too, are plots of land to be cultivated. I should emphasize again that the Arabs are not altogether absent from the walls of the Herzliya Historical Museum. They are woven into the Zionist story as its denied other, but cannot be ignored.

Such a folklorist view of the Arabs is seen in the picture that depicts “A Bedouin encampment around Sidna Ali.” It shows an Arab family as some ancient museum artifact from the area. Another image, very faded, shows seated Bedouins surrounded with tents and chickens in the area of the present neighborhood of Neve Amal. Perhaps these are the Shubaki people, some of whom, we were told by both refugees of Ijlil and Alharam, had been massacred by Jews to chase them away.

Neighborly “Understanding”

The Arabs were not only a part of the natural landscape for the Herzliya settlers; the museum also describes the relationship between the neighbors. The most prominent motif in these relations, at least in the beginning, was an “understanding.”

“At first Herzliya enjoyed an understanding with its Arab neighbors,” announces the wall display. It is worth lingering a moment at this simple statement, as it embodies the overarching Zionist view. The history of the land begins with Herzliya “from its beginnings” and “at first.” What is depicted here is not, heaven forbid, an act of colonialism, but the beginning of history, which commenced with Zionist settlement. Prior to this, according to the exhibit, the land had no history.

“At first” there was an “understanding” with the neighboring Arabs, but “trends of thought” rampant among “other Arabs in the country” influenced the “local villagers” as well, which forced the settlers to take “defensive measures.” The defensive “no choice” attitude is not merely a recent policy but was born in that distant dawn of time in our region. Suddenly the Arabs became a factor to be reckoned with, threatening the first settlers who had to react and defend themselves.

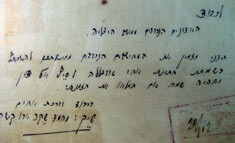

The subjectification of the Arabs takes place when the Zionist settlers become victims fighting for their lives. Here, too, there is something of the well-worn sentiment about “the good Arabs from here” versus “the bad Arabs from there.” The highlight of the representation of the close relationship between local Arabs and the Jews of Herzliya is expressed in the invitation that Sheikh Abu Kishek sent to all Herzliya residents to attend his brother’s wedding. Sheikh Ahmad Shaqar Abu Kishek sends his invitation in Hebrew and Arabic, signed “With brotherly greetings.”

A book written by one of the Herzliya’s earliest founders shows a picture of Jews and Arabs, with the caption “Encounters with Bedouin neighbors in the attempt to establish good neighborly relations.” This too is an important theme in the Zionist narrative. “We have always held out our hand in peace and good neighborliness.”

This picture also appears in the museum’s display as an example of neighborly relations, but its caption is rather embarrassing: “Settlers and members of the American Zionist community against the background of a Bedouin tent.” In the background indeed a Bedouin tent is visible, but in the foreground stand the Bedouins themselves.

The Arabs are the background, part of the landscape, even when they stand at the front. They are absent from the caption, just as they are from history, in writing and in print. In effect, they are transparent to the text that verbalizes the picture in which they appear. This is perhaps an early indication of the status of internally displaced Palestinian citizens of Israel, who have been defined by Israeli law as “present-absentees.”

Most of the persons shown in this picture are Arabs, but they remain nameless and overlooked. On the other hand, the settlers and their American patrons are the subject of the picture. The Arabs in the picture are a type of still-life, taken for granted, among which the colonization by the settlers and their patrons can take place. The Arabs do not make the wasteland bloom, they are a part of it. Wasteland is something that does not have a voice, does not speak. They are a part of the wasteland also in the sense that they don’t speak, their voice is not heard.

In this respect they must be there, in the picture, in physical space, to illustrate what must be redeemed. A good example of the Zionist ‘civilization’ that replaced Arab ‘primitivism’ is evident in the photograph (blurred in the original) of Arabs tilling their lands with a camel, mule, and ox. The caption reads: “Herzliya’s neighboring farmers plow with an ox and mule, civilization has yet to reach them.” When civilization (progress!) finally does arrive, these farmers no longer till their land. They become welfare recipients in refugee camps.

A crucial element of the “understanding” was the supply of vital needs such as water and construction materials to Herzliya settlers by Arabs. We are told that “Herzliya founders purchased fresh water from the Arab village Ijlil.” This was probably funded by the American Zionist community.

An impressive photograph depicts the pioneers, a man drinking water Arab-style from a jar, and a woman carrying a jug on her shoulder. Above this picture, the caption tells of Arabs from Ijlil supplying the settlers with water. Interestingly, the English caption distinguishes (Jewish) “settlers” from (Arab) “residents.”

Building materials, too, were brought from neighboring Ijlil. Ibrahim Abu Sneina, a refugee of this village, told us that his family mined building materials and transported them to the site where Cinema City is now located. A handsome photograph shows camels carrying sand for construction.

Gender relations are clearly reflected in the exhibited photos. A picture shows “Bedouin women from Sidna Ali fetching water from the mosque well” (page 5). The traditional role of women as drawers of water is replicated by the Hebrew pioneer woman, as we see in the previous photograph, where she is the sole woman among men and the only one carrying water. But unlike the Arab women, she carries her jug on her shoulder, rather than on her head. The Arabs were greengrocers, as well, as the next photograph shows. The impressive man “Abed gute mensch” stands flanked by two nameless women (probably Jewish) “from Herzliya Pituach,” riding donkeys.

“Persuaded to stay” in 1948

One of the timeworn myths surrounding the “War of Independence” is that Jews begged their Arab neighbors to remain, but that the latter refused and thus lost their property for good. At “Beit Rishonim,” too, this story appears prominently on the wall display about local events in the war: “At that time the Arabs of the region abandoned their houses, despite the attempts of Herzliya public figures to persuade them to remain.”

But a perusal of the book written by Ben Zion Michaeli, a mayor and one of the founders, reveals a more complex state of affairs. In the chapter on “The Arabs’ Escape” Michaeli relates how he, together with two other notables, met the chief of Ijlil and tried to persuade him to stay. The chief told him that the Arabs were very frightened because Jews were shooting at them at night, so they had no choice but to leave for a while.

Michaeli adds an interesting reason why it would be better for the Jews if the Arabs remained. This would make Arab assaults on them more dangerous because the neighboring villagers would guide the assailants. As mentioned earlier, the Shubaki massacre was known in the area and had caused panic among the surrounding villagers, as did the Deir Yassin massacre. In Herzliya, pioneers not only tilled the land. They took part in the war effort by preparing ammunition and fighter planes used in the airfield in town.

In sum, we have seen how the Herzliya museum depicts the development of the town from its ‘beginnings,’ how it constructs the Arabs of the area as part of the landscape, of the wasteland, which the settlers made bloom.

The museum was built by the successors to the founding settlers, who found it important to praise their forefathers’ undertaking. They write the history, select the photographs, articulate them in captions and mount them on the walls. In the history of the land Herzliya is the victor. The Arabs were defeated and they are not here. This is also clear in the manner in which the victors write this history.

Now “it’s wonderful here,” as the song by the Biluim, a Jewish Israeli band, goes. “The Arabs of Herzliya aren’t angry anymore. The Arabs of Herzliya are Russians.” Still, the silenced voices of the “Arabs of Herzliya” poke out from the cracks in the museum walls, as they do across the landscape. They refuse to be completely erased. The voices of those who have been expelled are clues that must be recovered. In our ability, as Jews in Israel, to hear the voices of the Palestinian refugees, lies the far-off chance of bringing about reconciliation in this land.

Eitan Bronstein founded Zochrot (Remember) which tries to educate Israelis about the history of 1948, including Israeli attacks on unarmed Palestinians and the destruction of more than 400 Palestinian towns and villages.